Israel’s King Saul

Saul, betrayed by many of the people he trusted most, is one of the great tragic figures of the Bible.

Samuel anoints Saul

He was born the son of Kish in Gibeah of Benjamin. It was a great moment to be born, because the Hebrew tribes were just starting to organize real opposition to the Philistines, their overlords. Saul emerged as a charismatic leader: “the spirit of God came mightily upon him” (1 Samuel 11:6).

He must have been capable, because the tribes rallied to him to lead them against the Philistines. Saul defeated the Philistines at Michmash. He drove them out of the highlands in about 1020 BC.

Now that they had a capable military leader, the Israelites began to realize what they could do and be, and this realization made them push for Saul be made king. After all, the surrounding groups and cities all had kings.

Saul’s Anointing

There was however a conservative minority who did not want a king. They wanted the old tribal league to stay the same.

Samuel seems to have been undecided on the matter. There are two parallel accounts of Saul’s election to the kingship, one being favourable to the monarchy, the other hostile.

- The story as it is told in l Samuel 9:1-10:16 records that Saul was privately anointed as ‘nagid‘ (prince) by Samuel in Ramah, and this is continued in l Samuel 13:13b, 4b-15.

- Side by side with this is a separate account of Saul’s victory over the Ammonites and his subsequent acclamation as ‘king’ by the people at Gilgal.

- The other account of the election puts the initiative in the hands of the tribal elders and the people: “Then all the elders of lsrael gathered together and came to Samuel at Ramah, and said to him, ‘Behold, you are old and your sons do not walk in your ways; now appoint for us a king to govern us like all the nations” (l Samuel 8 :4-5).

According to this tradition (l Samuel 8:6-18; 10:17-27; 12). Samuel yielded to a spontaneous popular demand for a king and presided over his formal election at Mizpah, only after angry protests.

The notion of kingship came late to lsrael. Many people saw it as an attempt to imitate pagan neighbours – and wasn’t this a betrayal of their tradition?

The ‘Manner of the King’

Samuel was deeply suspicious of monarchy, and he interpreted the people’s demand as a rejection of the idea of God being their leader.

He consulted God and, although he was directed to ‘hearken to the voice of the people in all that they saý to you,’ he also had to ‘solemnly warn them and show them the ways of the king’ (l Samuel 8:9).

His warning became a famous denunciation of monarchy. Samuel predicted that a king would

- impose heavy taxes on the people

- demand forced labour, the corvée service, on the common peoples, thus making slaves of them

- establish a standing army of draftees and professional soldiers

- expropriate property to give to his servants.

Samuel feared the change — but under pressure he agreed to the people’s demands (1 Samuel 8:4-22).

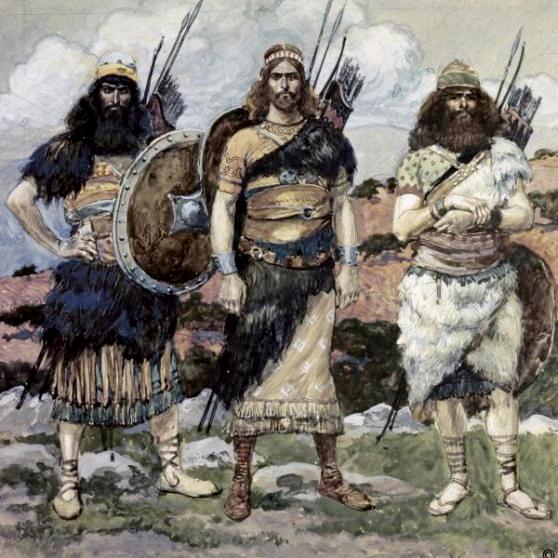

‘Three Captains’, by James Tissot

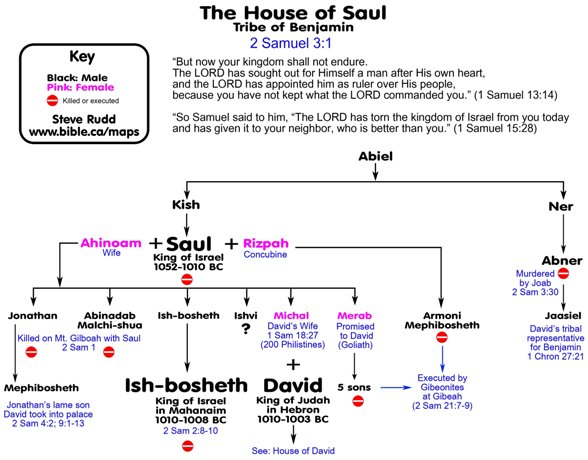

What was Canaanite government like?

Canaanite city states had small armed forces consisting of conscripted foot-soldiers and professional warriors recruited from the ranks of the aristocracy. These were the ‘maryannu‘, or what we would call ‘knights’.

Performance of military obligations exempted the knights from payment of tithes or other taxes.

Under the Canaanite system

- the kings owned the crown lands and leased vineyards, orchards and estates to chosen individuals against payment of taxes to the palace.

- the mass of the people had to pay a tithe (or tenth) of their crops and livestock in taxes, as well as grazing taxes, tolls and fines.

- they were subject to the corvée (forced labour) for the construction of roads, fortresses and temples and for tilling the crown lands.

I Samuel 8 may be a genuine appeal by Samuel urging the people not to impose an alien Canaanite way of life upon themselves.

Saul’s achievements

After rescuing the Israelites from the immediate Philistine danger, Saul led many military expeditions against the Moabites and Arameans. He was a warrior-king.

He also took an active part in the attempt to preserve Israel’s religious purity, and tried to suppress the witchcraft practiced by Hebrews and Canaanites alike.

Rivalry with David

The Bible reader must remember that Saul’s story is told by people who sympathised with David rather than Saul. The story always favors David, contrasting David‘s heroic personality, charm and popularity with Saul’s increasing nervous depression.

Saul had outbursts of passion, and seems to have been seriously disturbed. David, who was his cup-bearer and a close friend of his son, Jonathan, was detailed to calm him with music (I Samuel l6:l4-23).

Saul had outbursts of passion, and seems to have been seriously disturbed. David, who was his cup-bearer and a close friend of his son, Jonathan, was detailed to calm him with music (I Samuel l6:l4-23).

Saul grew increasingly jealous of David‘s spectacular military success and growing popularity – as well he might. Increasingly on the outer, David sought refuge with Achish, king of Gath – a treasonous thing to do.

Samuel Rejects Saul

Saul’s relationship with Samuel also shows him in a tragic light. For the greater part of Saul’s life he was on bad terms with the people’s venerated religious leader. The split between the two appears to have occurred quite early in Saul’s career.

- According to one tradition (I Samuel I3:4-l5), Saul had usurped the function of the tribal league priesthood.

- In the other, he is said to have violated the ‘herem‘ rule of the law regulating conduct of a Holy War. This rule decreed anathema (complete destruction) on the vanquished enemy and his goods.

Whatever the cause, Samuel broke with him finally and ‘did not see Saul again until the day of his death.’ (I Samuel 15:35).

Saul’s Death

A few years after Saul had driven David away from his court the Philistines rallied again.

They marched northwards to Beth-Shean, cutting the country into two and preventing the tribes of Galilee and Transjordan from joining Saul.

This also presented the Philistines with a battleground which was favourable for chariot manoeuvring. Saul had no chariots and could not withstand the assault of the heavy Philistine armour in the plain. He moved on to the higher ground of Mount Gilboa.

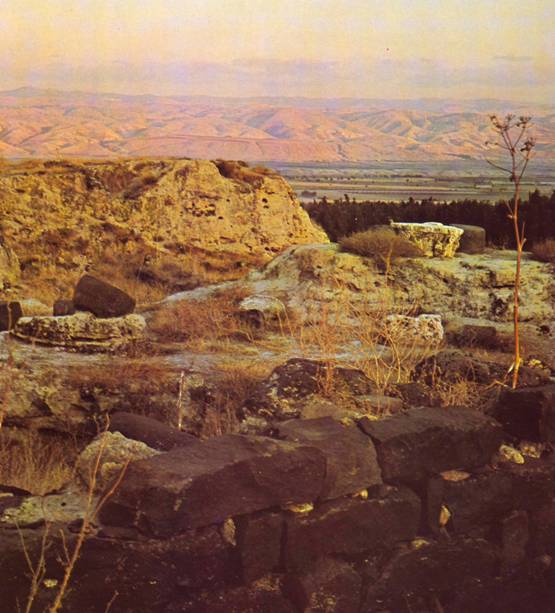

Mount Gilboa where Saul and his sons fought and died; the Plain of Jezreel below

Tradition has it that before the battle Saul visited a medium, the Witch of Endor, who conjured up the spirit of the departed Samuel from Sheol (the underworld), only to hear him pronounce the Curse of Doom on the fearful king (I Samuel 28:16-19).

Even after death, the prophet would not be reconciled to Saul.

On Mount Gilboa, Saul and his three sons, including Jonathan, were killed, and their bodies strung up on the city gates of Beth-Shean. The Philistines regained control of the country and kept it until well into David’s reign (circa 990 BC).

The ruins of Beth-shan. It was on these walls that the Philistines hung the dead body of King Saul.

It was David who was to establish the national unity of the Israelites, but he built on foundations which had been laid by Saul.

Saul falls on his sword, James Tissot

Saul’s sons

There is no way of knowing the age of Saul’s sons when they died beside him in that last  desperate battle on the slopes of Mount Gilboa – but they cannot have been much older than the boy soldiers in this tragic photograph from the American Civil War (at right).

desperate battle on the slopes of Mount Gilboa – but they cannot have been much older than the boy soldiers in this tragic photograph from the American Civil War (at right).

Young men are used in battle for several reasons:

- they are confident that nothing can really harm them – a cause, incidentally, of the high proportion of young men who die in car accidents

- they are sometimes seen as a last resort, when older, more experienced soldiers are no longer available

- they see war as an opportunity for adventure.

In Saul’s case, his sons fought because there was no other option. Their situation was desperate. Their father and his army faced overwhelming numbers and defeat was almost certain.

In the event of defeat, the princes would be executed by the enemy. Royal princes in the ancient world were never allowed to survive the overthrow of their father. This is why, for example, the seventy young princes of the Royal House of Omri were beheaded by Jehu when he killed King Joram and his mother Queen Jezebel.

Notes on Samuel’s choice of Saul

1 Samuel 7:15-12:25 Saul becomes king

- 7:15 – 8:3 Samuel’s position in Israel. Samuel, like Eli before him (4:18), was a judge in Israel, both a leader and deliverer raised up by God, and a judge in the modern sense. His life revolved round a number of sanctuaries, and he was widely venerated. Despite this, his sons were not admired, nor did they deserve to be.

- 8:1 Samuel’s sons were judges in the juridical sense only.

- 8:2 Beer-sheba is mentioned because it lies at the southern extremity of Palestine, and the writer wants to show the extent of Samuel’s influence.

- 8.3 The frequent unsuitability of men to succeed their fathers is a recurring theme of the Bible’s historical books, from Gideon to the descendants of David.

- 8:4-9 The popular plea for a king. We can understand the elders’ demand from a political point of view. Stability was what Israel lacked, as the turmoil described in Judges shows. The tribal elders connected this turmoil with the lack of stable leadership. But from the religious point of view, the demand (however sensible and far- sighted politically) was tantamount to rejecting Yahweh as king. This was abhorrent for one reason only: kings established dynasties. This is the thinking behind the whole story of Saul. Judges were individually appointed by Yahweh, at times of His choosing; Israel’s defeats had been caused by their own sins, not by the judges’ political incompetence. But instead of learning this lesson from their past history, and showing repentance and trust in Yahweh as a result, the elders considered that a stable leadership would prevent the ups and downs of the pas. This decision amounted to an attempt to bypass God, and in effect rejected His future leadership and power of choice, despite the willingness of the elders to allow Him (through Samuel) to select the first king.

- 8:5 Like all the nations. Many of Israel’s neighbours had long-established monarchies; the desire to ape foreign peoples was in itself a sign of apostasy.

- 8:10-22 Samuel’s advice was rejected. His speech paints a grim picture of the side-effects of a monarchy: forced labour and conscription, heavy taxes, and finally sheer despotic tyranny. Once Israel has chosen, there is no turning back. Moreover, evidence (from Alalakh and Ugarit) makes it plain that ‘the nations round about’ long before Samuel’s time had bitter experience of the cost of the privilege of having a monarchy. But we are not to suppose that God’s hand was forced. The situation did indeed need desperate measures, and the divine plan all along was to choose an anointed king in God’s own good time.

- 9:1-14 Saul comes to Ramah. The scene shifts, with skilful dramatic effect, to the man who was soon to become Israel’s first king. Saul’s lack of personal ambition is emphasized by the narrative: he was merely looking for lost donkeys, with no thought in his head of political greatness; he did not even recognize Samuel when he met him! Nevertheless, he came from a family of substance and his own personal appearance was kingly enough.

- 9:1 Perhaps ‘a man of Gibeah of Benjamin’ was the original reading; although neither the Heb- rew manuscript nor the ancient versions give the place-name. A man of wealth represents a Hebrew phrase often referring to valour (‘a mighty man of power’); here wealth is certainly intended, but possibly valour too.

- 3-5 The route cannot be traced in full detail, but it was no straight road. The denouement took place in Ramah, Samuel’s home-town. The name Ramah has probably been deliberately avoided, because the narrator, a skilful raconteur, does not wish to give the game away too soon that a meeting with Samuel is imminent

Search Box

![]()

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher