Childbirth in the ancient world

Was it different to modern childbirth?

For a start, we know that professional midwives assisted at the birth of a baby:

- Genesis 35:17 refers to a midwife when Rachel had her last son

- Exodus 1:15 describes the Hebrew midwives in Egypt.

How did a young mother give birth?

Exodus 1:16 suggests that a woman in labour sat on two stones placed a small distance from one another, to provide the equivalent of the birth-chair.

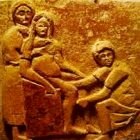

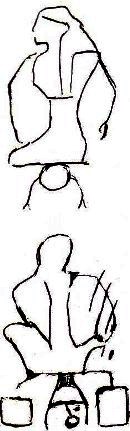

Women giving birth, helped by two other women.

Bronze Age clay statuette from Cyprus

On the other hand, children are also described as being born ‘on the knees of’ another person (Genesis 30:3; 50:23; Job 3:12). This may mean that childbirth took place on the knees of a midwife or relative helping the mother – a custom which is still practised in many parts of the world today.

The two Egyptian hieroglyphic signs at right, both meaning ‘to give birth’ also show

The two Egyptian hieroglyphic signs at right, both meaning ‘to give birth’ also show

- (top) that the Egyptians had observed the occipital position of the head in a normal birth and

- (bottom) that Egyptian women followed the common practice among early peoples and adopted a squatting rather than recumbent position during labour.

ln cases of multiple births, the rights of the first-born were jealously guarded and the birth sequence carefully noted (Genesis 25:25; 38:27).

Care of the new baby

The newborn was given special care (Ezekiel l6:4), washed, rubbed with salt and wrapped in swaddling clothes (Ezekiel l6:4; Job 3818-9).

The mother would nurse the baby (Genesis 21:7; 1 Samuel 1 :21-23) unless, probably among the wealthier classes, a wet nurse was hired (Genesis 24:59; 35:8; Numbers 11:12).

Apparently the baby was weaned at the age of three (11 Mac. 7:27), a custom which can still be found among local peoples and which held good in Babylonia during the period of the Second Temple. lt is also confirmed in the Talmud.

On the day the baby was weaned, a great feast was held (Genesis 21:8).

Naming the child

The baby was named as soon as it was born, usually by the mother (Genesis 29:32; 30:24; 35:18; I Samuel 1:20), although sometimes the father would choose the name (Genesis 16:15; 17:19; Exodus 2:22).

The name chosen might include the name of God (El, Yahu) such as Jehoiakim, meaning ‘God will arise’ or El-nathan, ‘God gave’, or many others. This name might be shortened, for instance Jakin from Jehoiakim or Nathan or Nethaniah from El- nathan.

Other popular names were those of living things, Deborah (bee), Shaphan (rabbit, hare), Ze”ev (wolf), etc., implying the wish that the child would have the quality of its namesake: as busy as a bee, as quick as a hare, and so on.

Names from the plant world, Allon (Elon, oak), Tamar (palm), can be explained in the same way.

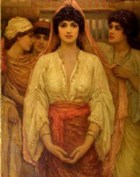

The ‘Marys’ of the New Testament period (Mary Magdalene, Mary mother of Jesus, Mary of Bethany ) were probably named after Mariamme, the beautiful young wife of King Herod the Great, who murdered her. See at right Waterhouse’s painting of the condemned Mariamme on her way to execution.

The ‘Marys’ of the New Testament period (Mary Magdalene, Mary mother of Jesus, Mary of Bethany ) were probably named after Mariamme, the beautiful young wife of King Herod the Great, who murdered her. See at right Waterhouse’s painting of the condemned Mariamme on her way to execution.

Occasionally the child might be named for an outstanding trait or feature or, more rarely, for an outstanding event coinciding with its birth. Biblical names of this type include Ichabod (literally ‘without honour’) translated as ‘The glory is departed from Israel’ (l Samuel 4:21) and Jacob, ‘. .. and his hand had hold on Esau”s heel’ (Genesis 25:26) etc., but the biblical interpretations follow a folk etymology.

Sometimes the names are self-explanatory, for example lthamar, Eshbaal, Jesse, meaning ‘my Lord’.

Aramaic names later became common, especially during the New Testament period, when Aramaic became the vernacular of everyday life. At about the same time, Greek names are found beside — or instead of — Hebrew ones, e.g. Jonathan, Theodoros, or a Semitic name was given a Greek form, Jeshua becoming Jesus, or Miriam becoming Maria.

Adopting a child

Adoption is the legal means of acknowledging a person of different blood as a son or daughter with the legal rights and duties of a true child. By this act, the adopter undertakes all the responsibilities and rights of a father towards the adoptee, who becomes in all legal respects his son or daughter.

This rag doll, which may have been either a child’s toy or a votary offering, dates from Hellenistic times.

In general, the purpose of adoption in the Bible is to provide support for the adopter, either in the shape of additional labour at the moment, or as a provision for his old age.

The custom was well known in Mesopotamia in ancient times and evidence for it has been preserved in Nuzi (where it was sometimes used as a way of evading the ban on the sale of property), in Assyria, and from Babylonian law.

The Code of Hammurabi devotes nine paragraphs to adoption. Their deeds of adoption made express provision for the adoptee’s share in the inheritance with the natural sons (born or unborn) of the adopter.

In the early days, the purpose of adoption was to provide an heir, to carry on a name or to preserve property. lt was also a means of ensuring additional labour.

With the growth of a slave system, adoption became unnecessary and therefore little practised. There are very few adoption contracts known in either Babylon or Assyria after about 1200 BC onwards.

A similar picture emerges from the Bible. The only clear reference to the adoption of a stranger in the Old Testament occurs in the story of the slave, Eliezer, whom Abraham proposed to manumit and adopt should he remain without issue (Genesis 15:3).

This reflects the practice in Nuzi where, according to documents unearthed there, a childless person could adopt his slave, who would provide for his adopter‘s old age and, in return, inherit when he died.

While this is evidence of the influence of Mesopotamian customs in ancient biblical times, it does not prove that the custom took root in lsrael (the Bible does not describe the action as adoption).

While this is evidence of the influence of Mesopotamian customs in ancient biblical times, it does not prove that the custom took root in lsrael (the Bible does not describe the action as adoption).

After the Patriarchal period there is no reference to adoption of children and the subject is totally ignored by the Mosaic Law. This suggests that the practice was unknown or at least not recognized officially in lsrael. The Jewish family was strictly a matter of blood relationships and no legal formulae could be a substitute for natural kinship.

The explanation given for the custom of Levirate marriage confirms the assumption that adoption was not regarded as a practicable means of ensuring the continuity of a man‘s ‘name’ when he could no longer beget children.

ln any case, in a society where polygamy was legitimate and divorce for a man relatively easy, a man whose wife was barren could always marry another to ensure his posterity, the assumption being always that it was the wife who was barren – never the man.

All the cases of apparent adoption in the Bible include some actual family tie:

- When Laban agreed to Jacob’s marriage to Rachel, he also adopted him as his son (Genesis 29) but they were, in any case, already related (29:10).

- Rachel adopted the children of her maidservant, Bilhah (30:3), but they were undisputedly Jacob’s children.

- On his deathbed, Jacob adopted Menasseh and Ephraim (Genesis 48:5-6) as his own sons, but they were in fact his grandsons, and similarly

- Joseph adopted his great-grandsons, i.e. the sons of Machir, the son of Menasseh “were born upon Joseph‘s knees“ (50:23).

- The story of Moses who was brought to Pharaoh’s daughter and ‘became her son’ (Exodus 2:10) seems at first another case of adoption, but scholars now believe that it may rather have been a similar situation to that of Genubath, the son of Hadad, who was brought up ‘in Pharaoh’s house among the sons of Pharaoh’ (l Kings 11:20).

- When Mordecai took Esther for his daughter after the deaths of her father and mother (Esther 2:7,15), this was closer to true adoption, but she too was the daughter of his uncle, not a complete stranger, and there is nothing in the story to suggest the legal obligations he had undertaken with this adoption.

Search Box

![]()

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher