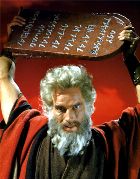

Who was Aaron in the Bible?

His story with Moses and Miriam

- Aaron was the older brother of the great prophet and leader Moses.

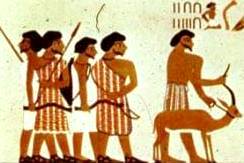

Travellers, possibly Hebrews, from an Egyptian mural at Beni-Hasan

- He seems to have acted as Moses’ spokesman whenever there were important speeches to be made – for example, when Moses appeared before a large group of people (Exodus 4:30-31), or before Pharaoh. Why was this necessary? No-one is sure, but perhaps Moses was simply not a gifted speaker – and Aaron was. Of perhaps Moses stuttered or simply got very nervous.

- Aaron took part in the miracles or “signs” which showed that the Israelite god was superior to anything the Egyptians could muster (7:8-12). When God sent the ten plagues against Egypt it was Aaron who stretched out his rod to turn the Nile water to blood (7:19-20) and stir up the plagues of frogs (8:5-6) and gnats (8:16-17).

- It was Aaron too who was summoned each time to avert the plagues (8:8 etc).

The waters of the Nile seemed to turn into blood

Aaron took part in a contest with the magicians of Pharaoh, and turned his staff into a snake

- At the battle of Rephidim he stood at Moses’ side and helped to support his uplifted arms to ensure victory over the Amalekites (Exodus 17_8-13).

- At the meeting with Jethro (Exodus 18:12) and again at Sinai (Ex. 19:24; 24:1, 9) Aaron was Moses’ companion and aide.

- These earlier traditions do not show Aaron as a priest or an ancestor of priests. On the contrary, Aaron opposes Moses on religious questions, leading a revolt with his sister Miriam (Numbers 12) and even making the Golden Calf (Exodus 32).

The nomadic Hebrew tribesmen with Aaron, Miriam and Moses may have looked like this. From a tomb mural at Beni-Hassan in Egypt

Aaron’s background

There is very little information about Aaron’s and Moses’ ancestry. In fact, the names of his family have a distinctly Egyptian sound: Phinehas, Putiel, and Hofni – but this would make sense, since they had been slaves in Egypt for many years.

Aaron’s claim to leadership alongside Moses appears to have been fully accepted by all the Israelites.

These stones, excavated at the ancient city of Megiddo, were probably part of an ancient sanctuary

Who’s telling the story?

Keep in mind that these ancient stories were first composed before Jerusalem and its Temple became the focus of the Israelites.

At that time there were dozens, maybe hundreds of sanctuaries at different places in the country.

- There were no official priests attached to a religious centre in Jerusalem,

- and ordinary people as well as religious officials could preside over religious ceremonies and sacrifices at the altars (Exodus 23:19).

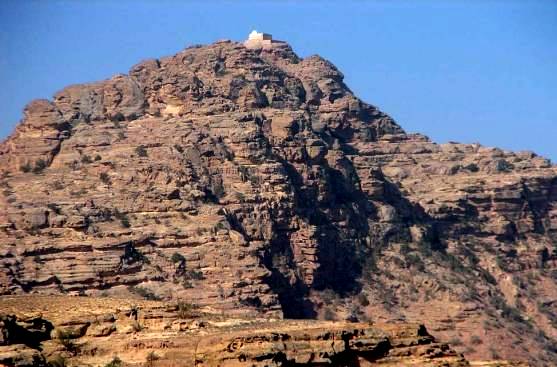

The ruins of a simple ‘high place’ at Petra,

where ordinary people might offer sacrifice.

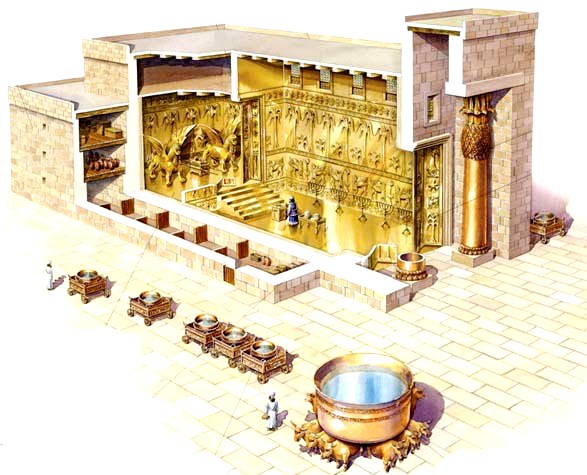

But the priestly writers who gathered the stories together at a later date, assumed that a tabernacle of the dimensions and magnificence of a full-scale Temple was erected very soon after the events on Mount Sinai.

Reconstruction of Solomon’s Temple

built many hundreds of years after the time of Aaron

They also assumed that the duties of the priests were laid down at the same time.

In fact however, the organization of the priesthood came at a much later period when there was a capital city, Jerusalem, and a Temple familiar to everyone.

Quite obviously, Aaron could not have fulfilled the function of a priest during the bondage in Egypt, or in the wilderness when the Israelites had no real sanctuaries. Even the description of him as “the Levite” in Exodus 4:14 probably reflects no more than the general feeling that his office was more appropriate to a member of the Levi clan.

Later on, the terms “Levite” and “priest” were to become practically synonymous and this is a case of the meaning being imposed on the older tradition at a later date.

The Golden Calf

One of the early traditions of Exodus 32 records that because Moses “delayed to come down from” Mount Sinai, the people gave up hope that he would ever return, and demanded that Aaron make them gods to worship.

Bronze bull excavated in northern Israel. The bull, cow and calf were symbols of fertility, in crops, flocks & people.

Under pressure, Aaron acquiesced. He had the men collect their womenfolk’s gold jewellery and from it made them a molten calf “fashioning it with a graving tool” (Exodus 32:1-4).

A sacrificial altar was built before it and burnt sacrifices offered, Aaron presumably officiating.

Worship of the forces of Nature continued for hundreds of years after settlement in Israel.

Aaron Revolts Against Moses

In Numbers 12, Aaron challenges Moses’ authority. Perhaps he feels he has more ability to lead than Moses has, and that the weary Hebrew tribespeople will follow him more gladly.

In any event, he and his sister Miriam complain about Moses’ marriage to a Cushite woman.

But the real reason for their protest seems to have been their resentment of Moses’ unique position as the mouthpiece of God. They too, they argued, had received divine revelation, “Has the Lord indeed spoken only through Moses? Has he not spoken through us also?” (Numbers 12:2).

The face of a leprous woman

Their insolence was answered by God in the form of a pillar of cloud proclaiming his complete confidence in Moses who “is entrusted with all my house.” (12:7).

Punishment for their lèse majesté was rather unfairly limited to Miriam. She was tormented by a skin ailment that the Hebrews believed was leprosy, and excluded from the camp for seven days.

But her brother Aaron stood by her, interceding with Moses, and she recovered. He himself had not suffered, it was said, because he had priestly status.

The fact that the Israelites halted their march for the time that Miriam was in disgrace suggests that her “sin” may possibly have involved others beside herself and Aaron.

Aaron as High Priest and Priestly Ancestor

In other parts of the story, Aaron seems to be quite a different character. He is Aaron “the Levite”, i.e. an officiating priest, Moses’ religious vice-regent and the first High Priest of Israel. From him all lawful priests must be descended, other members of the tribe of Levi acting as their servants (Exodus 28, 29 and 39; Leviticus 8-l5; Numbers 17-18).

Ancient sacred vessels for the burning of incense

Throughout the “priestly” regulations for the tabernacle and religious organization, the phrase “Aaron and his sons“ is used to mean the priesthood in general.

They cannot have reached this position without meeting opposition, which is probably echoed in

- the unfavourable stories of the Golden Calf (Exodus 32) and

- the rebellion of Aaron and Miriam (Numbers 12).

Many scholars consider that the story of the Calf was the basis for the consecration of Levites to the service of the Lord (Exodus 32:29) for on this occasion they proved their unquestioning loyalty to God.

Later on (Ezra 2:61-63), Levites and priests who could not claim undisputed descent from the house of Aaron were excluded from service at the altar and limited to subsidiary duties.

Aaron and the story of the priesthood

The way Aaron and his role are presented can best be understood in terms of the long story of the priesthood, first of all in the sanctuaries throughout Israel, then in Jerusalem.

The contradictory accounts of Aaron’s role in the Exodus reflect the struggle between different groups of priests.

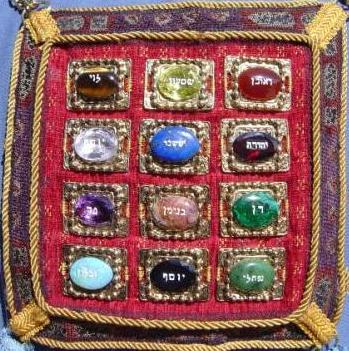

Breastplate of a priest

The most widely accepted theory is that

- the priests who returned from Babylon at the time of Ezra and who were probably descendants of Zadok (King David’s High Priest, apparently a Levite with no special pedigree), had somehow to amalgamate with

- a non-Zadokite group claiming descent from Aaron, who had stayed on in Palestine during the Exile. These priests were from the family of Abiathar and they claimed to be descendents of the house of Eli which, they maintained, had been selected as priests while the Israelites were still in Egypt (I Samuel 2:27-28).

Over time, as Aaron became acknowledged the first High Priest of Israel, they also claimed descent from him. During the long period of sanctuaries, before the building of the Jerusalem Temple, there was no great urgency in the disputes between the rival priestly families.

But when all worship and priestly privileges were centred in the Jerusalem Temple, particularly after Josiah’s reform, the struggle for recognition became much more acute.

Eventually, after the Exile, an agreement was reached by which the two leading families shared the priesthood on an equal footing as “Sons of Aaron”.

Aaron dies

Aaron died in the 39th year of the Israelites‘ wanderings, on the eve of the Conquest. Numbers 20:23-29 records his death on the top of Mount Hor, on the borders of Edom.

23 And the LORD said to Moses and Aaron at Mount Hor, on the border of the land of Edom, 24 “Aaron shall be gathered to his people; for he shall not enter the land which I have given to the people of Israel, because you rebelled against my command at the waters of Mer’ibah. 25 Take Aaron and Elea’zar his son, and bring them up to Mount Hor (the location of this mountain is unknown; 26 and strip Aaron of his garments, and put them upon Elea’zar his son; and Aaron shall be gathered to his people, and shall die there.”

27 Moses did as the LORD commanded; and they went up Mount Hor in the sight of all the congregation.

28 And Moses stripped Aaron of his garments, and put them upon Elea’zar his son; and Aaron died there on the top of the mountain. Then Moses and Elea’zar came down from the mountain.

29 And when all the congregation saw that Aaron was dead, all the house of Israel wept for Aaron thirty days (the usual mourning period was seven days).

Mount Hor, the traditional place of Aaron’s death.

See the building at the summit, the supposed spot where Aaron died.

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher