The Madonna and Jesus

Hidden meanings in Madonna paintings

To understand paintings of the Madonna Mary, you should know that…

- People believed there had been actual portraits of Mary painted by St Luke.

- The Church had a guarded attitude to women. After all, Eve the temptress had been a woman…

-

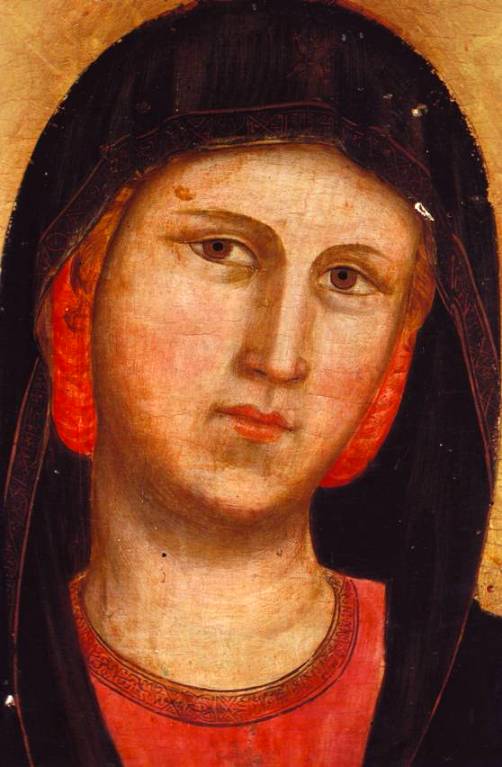

Madonna with

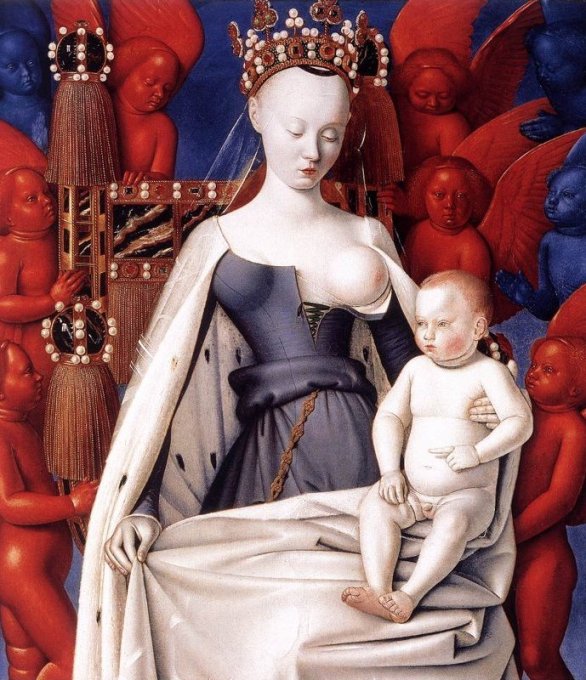

the Child Jesus, CrevilliThere is no attempt at historical accuracy. Painters, especially in the Renaissance period, painted Mary as a queen (see right) even though they knew that she was a 1st century peasant girl from rural Palestine. Modern painters try to show her with some historical accuracy; medieval painters had no such inhibitions.

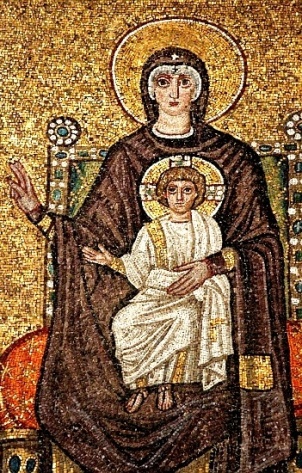

- Medieval paintings of the Madonna Mary show a mother figure, very like the goddesses in ancient religions. Not everybody was happy with this, and various people challenged the idea: the Nestorians in the 5th century AD, and the Reformation in the 16th century. Nestorius denied that the Virgin could properly be called the ‘Mother of God’: she was the mother only of Christ the human, not the divine person. That view was soundly rejected by the Council of Ephesus in 431 AD, and the image of ‘Mother and Child’ received the official stamp of approval.

Images of a mother goddess already existed in many pagan religions, notably that of the Egyptian goddess Isis holding her son Horus in her lap (see right) which survived well into the Christian era in several Mediterranean countries. The early Church simply adapted it.

Images of a mother goddess already existed in many pagan religions, notably that of the Egyptian goddess Isis holding her son Horus in her lap (see right) which survived well into the Christian era in several Mediterranean countries. The early Church simply adapted it.- Majestic images of the Virgin and Child enthroned became common in the West in the 7th century. They remained through the Middle Ages as a statement of faith. You can see this in inscriptions like ‘Mater Maria Dei,’ and ‘Sancta Dei Genitrix.’

Was Mary, the Madonna, worshipped?

In the 12th and 13th century there was something labelled ‘Mariolatry’ – idolatry of Mary. It happened in the era of religious devotion following the Crusades. It reached its most fervent form in the Gothic cathedrals of France, which were often dedicated to ‘Our Lady’ — ‘Notre Dame’, see right the statue of Mary in Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris.

In the 12th and 13th century there was something labelled ‘Mariolatry’ – idolatry of Mary. It happened in the era of religious devotion following the Crusades. It reached its most fervent form in the Gothic cathedrals of France, which were often dedicated to ‘Our Lady’ — ‘Notre Dame’, see right the statue of Mary in Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris.- Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) interpreted the Song of Songs as an elaborate allegory in which the bride of the poem was identified with the Virgin. That idea became the basis of much of the imagery surrounding the Virgin.

- The Renaissance saw more relaxed images of the Virgin and Child, among them the Madonna of Humility seated on the ground, and the Mater Amabilis ‘lovable mother’, perhaps the favourite image in the whole of Christian art.

There were several other forms – among them were the Virgin of Mercy who sheltered the penitent under her ample cloak, or knelt before Christ at the Last Judgement to intercede for the souls of the dead; and the Mater Dolorosa who grieved for her son, her breast pierced by seven swords symbolizing her seven sorrows (see right), or sitting with his dead body in her lap – as in Michelangelo’s Pieta.

There were several other forms – among them were the Virgin of Mercy who sheltered the penitent under her ample cloak, or knelt before Christ at the Last Judgement to intercede for the souls of the dead; and the Mater Dolorosa who grieved for her son, her breast pierced by seven swords symbolizing her seven sorrows (see right), or sitting with his dead body in her lap – as in Michelangelo’s Pieta.- The Virgin traditionally wears a blue cloak and veil, the colour symbolic of heaven and a reminder that Mary is the Queen of Heaven.

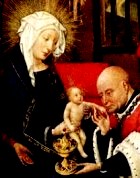

The Madonna breast-feeds Jesus

- The Virgin suckling the infant Christ (the ‘Virgo lactans’ or ‘Maria lactans’) is the most ancient type of Virgin and Child. What is thought to be the earliest example is a 3rd century fresco in the Christian catacomb of Priscilla at Rome (see right)

which shows a seated woman holding a naked infant to her breast and apparently suckling it. This idea probably came from the image of the Egyptian goddess Isis nursing her son Horus.

which shows a seated woman holding a naked infant to her breast and apparently suckling it. This idea probably came from the image of the Egyptian goddess Isis nursing her son Horus. - In the 5th cent. the Nestorians’ ridiculed the idea that the godhead could be suckled by a human woman. But this only encouraged its representation – so much so that in Italy in the 14th century many churches claimed to possess some of the Virgin’s milk, preserved as a holy relic. The Church stepped in at the Council of Trent: it solved the problem by forbidding undue nudity in the portrayal of sacred figures…

Queen of Heaven

The Virgin and Child Jesus, Ravenna

- The Virgin enthroned, or Regina Coeli, the Queen of Heaven, is more often than not accompanied by the Child. The earliest examples in the West are seen in the mosaics at Ravenna (see right) and elsewhere.

- In early Italian painting the theme falls into three main types: the full-face frontal view of the Mother and Child, deriving from Byzantine art; the Virgin pointing to the Child, and the more relaxed image in which the Child Jesus is embraced.

- The Virgin is sometimes depicted in an attitude of adoration and is then called the ‘Madre Pia’. Since her hands are joined the Child necessarily lies in her lap or on the ground. A similar sentiment is depicted in one type of the Nativity in which the Virgin kneels in prayer before the Child who lies on the ground.

- There may be a book close to the Virgin and Child. Never mind the historical accuracy: books were a common accessory in Renaissance painting. It is traditionally the book of Wisdom and marks the Virgin as the ‘Mater Sapientiae’, the Mother of Wisdom. When held by the Child the book represents the gospels.

- From early times the rose had a place in Christian symbolism, the red bloom signifying the blood of the martyr, the white, purity, especially that of the Virgin, who was also called the ‘rose without a thorn’.

- The image of the garden itself is drawn from the Song of Songs where the ‘enclosed garden’ (4:12) was made to stand for Mary’s virginity.

- The Madonna of Humility appeared in northern Italian paintings in the 14th century. Its essential feature is that the Virgin is seated on the ground, perhaps on a cushion. Medieval theology regarded humility as the root from which all other virtues grew, an idea appropriate to the Virgin from whom Christ grew.

Common symbols of Mary

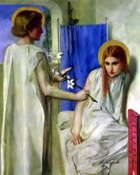

- LILIES, ancient symbol of purity particularly associated with the Annunciation

- STARS, usually seen on the Virgin’s cloak, relating to her title ‘Star of the Sea’ (Latin: Stella Maris), the meaning of the Jewish form of her name, Miriam.

- the TREE OF JESSE, the genealogical tree of Christ, stemming from Jesse, the father of David (Isaiah 11:1-2).

- the SERPENT, symbol of Evil or the Devil, usually shown crushed under Mary’s foot (see right)

- the APPLE, usually held in the infant’s hand, is traditionally the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge and therefore alludes to him as the future Redeemer of mankind from Original Sin.

- the ORANGE in Dutch painting has the same meaning (Dutch: Sinaasappel, Chinese apple).

- GRAPES symbolize the eucharistic wine and the Redeemer’s blood. A black bunch and a white probably allude to John’s account of the wounding of Christ on the cross ‘and at once there was a flow of blood and water.’ (19:34).

- Ears of CORN, in association with grapes, stand for the bread of the Eucharist.

- The POMEGRANATE, a fruit with several symbolic meanings is here used to signify the Resurrection. It was in antiquity the attribute of Proserpine, the daughter of the corn-goddess Ceres, who every spring renewed the earth with life, hence its association with the idea of immortality and its Christian counterpart, the Resurrection.

- A BIRD in pagan antiquity signified the soul of man that flew away at his death, a meaning that is retained in the Christian symbol. It is generally seen in the hand of the Child, and is most commonly a goldfinch. Its handsome plumage once made the goldfinch a favourite pet with children. The reason for its association with the Christ Child was the legend that it acquired its red spot at the moment when it flew down over the head of Christ on the road to Calvary and, as it drew a thorn from his brow, was splashed with a drop of the Saviour’s blood.

Madonna del parto (the Pregnant Madonna) Piero della Francesca

Madonna and the Child Jesus, Botticelli

Virgin and child enthroned, Quentin Massys

Mary with her son Jesus, Marseilles Cathedral

The Virgin with sleeping child, Andrea Mantegna

The Virgin is dressed with the utmost simplicity; below her head-cloth, several strands of hair hang loose. With her hand she holds the sleeping Child tenderly to her breast. A golden cloak embroidered with a pattern of pomegranates enfolds Mary and the Child like a shawl. The Child is tightly wrapped in swaddling-clothes, so that only the head and hands are visible. This may have been customary at the time, but it is rather suggestive of a corpse wrapped in winding-sheets. There is a possibility that the painter intended an allusion to the death of Christ, and in the action of the mother holding her son to her breast anticipated the representation, which later became widespread, of the Pietá, depicting Mary With the dead Christ on her lap.

Madonna and child, Michelangelo

Michelangelo left this marble group of a Madonna and her child unfinished in his Florentine studio when he left for Rome in 1534. The Virgin is seated with her left leg crossed over her right. Straddling the raised leg is the large, muscular child who turns away from us, seeking his mother’s breast. Michelangelo has depicted an unusual moment, for the child is neither suckling nor is he comfortably situated on his mother’s leg; instead he is shown in mid-action, uncomfortable and unfulfilled. The child contrasts with the distant, immobile mother. The two figures engage in a lovely gestural counterpoint, each with a hand on the other’s shoulder. The counterclockwise turn of the child is matched by a less violent opposing clockwise motion of the mother. Her left shoulder is forward and hunched down, as if she were offering herself to her child, and her right arm rests on the rear of her seat as if counterbalancing his weight. The child is enfolded in the protective embrace of his mother, yet at the same time, their contact is more physical than emotional. The mother gazes into space, classically beautiful but infinitely remote.

Madonna and Saints adoring the Child Jesus, Perugino, detail.

It is most unusual to use red as the color of Mary’s dress – red is the color of passion. But Perugino painted many images of the Virgin, and in most of them she is wearing a red gown. What was Perugino’s message?

Botticelli Madonna

Madonna, Jean Fouquet

Madonna of Humility, Fra Angelico

Madonna and child, 11th century Anglo-Saxon carving

Spanish Madonna, wood carving

Crown of the Madonna from a Giotto painting

The Madonna, detail from a Giotto painting

And now for something completely different…

Caravaggio’s sumptuous and controversial painting of the death of Mary

![]()

Bible Study Resource for Women in the Bible

Paintings of the Madonna Mary, Mother of Jesus

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher