Moses and archaeology

The Bible story linked with historical fact

Was Moses really an Egyptian?

Some scholars argue that Moses was not Hebrew, but Egyptian. Why? They link Moses with the mysterious Pharaoh Akhenaten.

The desecrated sarcophagus of Akhenaton, Cairo Museum

Akhenaten did something very similar to Moses: he abolished the cults and idols of polytheism and insisted on a purely monotheistic worship. This of course is just what Moses did.

- Was the Bible’s Psalm 104 simply a Hebrew translation of Akhenaton’s Hymn to the Sun?

- Didn’t the Egyptian Sun God Aton and the Hebrew Adonai have virtually the same name?

- Was Moses actually an Atonist, close to the Egyptian ruler and supporting him in his attempt to establish worship of a single god?

- Or was the biblical Moses a memory of the forgotten Pharaoh himself?

- Were the Chosen People really Atonists escaping from Egypt after Akhenaton had died, fleeing for their lives as the newly re-instated priests cleansed the whole of Egypt of worship of Akhenaten’s One True God?

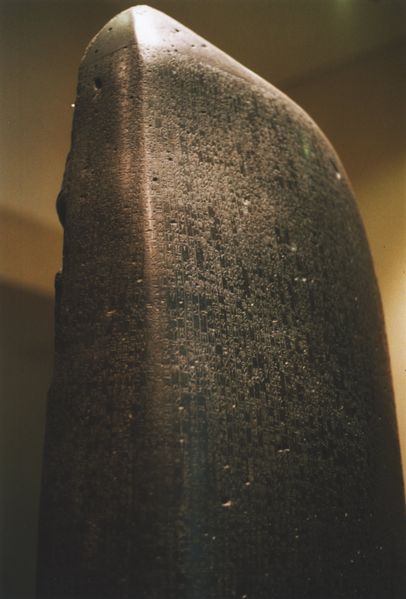

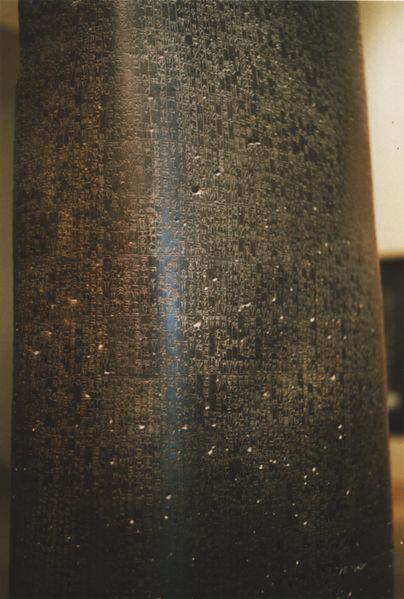

Moses’ Stone Tablets – ancient stelae?

The Bible says that when Moses went up onto Mount Sinai, he was given ‘stone tablets’ by God (see Exodus 20 and 34).

- What were the stone tablets?

- Were the stone tablets of Moses like the ancient stele of Hammurabi?

Moses’ tablets were engraved with a long list of commands that were actually a law code for the ancient Hebrew people.

The Tablets of the Law, as described in Exodus 20 and 34, bear a striking resemblance to the stele on which the Laws of Hammurabi were carved.

Moses Smashing the Stone Tablets, Rembrandt. The artist portrays the tablets as slate slabs

Moses, marble statue by Michelangelo in San Pietro in Vinculi. Here, the stone tablets are fine slabs of marble

The Stele of Hammurabi was made of polished black diorite in circa 1800BC in Babylon. The text is Cuneiform. The stele is held in the Louvre Museum, France.

Hammurabi had authority to give judgement on points of law, and to apply punishments when the law was broken

The stele bears a striking resemblance to descriptions of stone tablets given to Moses

Hammurabi’s Laws v. 10 Commandments

The great lawmaker Hammurabi instructed that the laws on the Stele were intended for future generations, and in fact the Code of Hammurabi was used in schools in Mesopotamia for another thousand years.

In the Israelite tradition, fathers had to teach their children the commandments, and people met together at regular intervals to listen to a reading of the Law.

There were certainly differences between the two sets of laws. The laws of the Old Testament were predominantly

- ‘apodictic’ – they began with ‘thou shalt’ or ‘thou shalt not’

- whereas most ancient law codes were ‘casuistic’: ‘when a man…., he shall….’.

But the actual tablets were probably similar to the stele of Hammurabi.

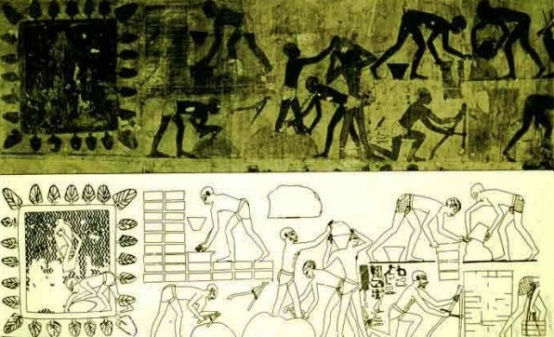

Brick-making in ancient Egypt

Wall relief showing Semitic laborers in Egypt making bricks with clay and straw (15th Century BC), as the Hebrews did when enslaved in Egypt

The caption that accompanies this wall painting says that they are ‘captives whom his majesty brought, for the works of the temple of Amon”. It also says that ‘the taskmaster says to the builders: “The rod is in my hand; be not idle.”

Some Egyptian texts mention brick quotas and a lack of straw, just as Exodus 5 does.

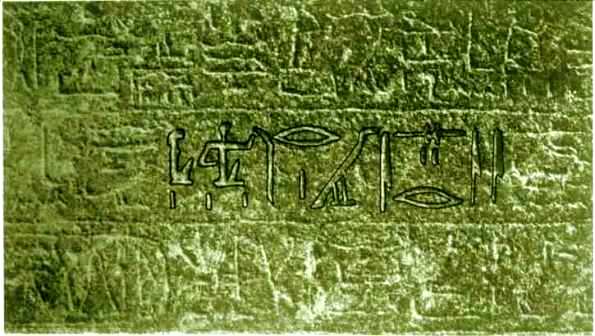

First mention of ‘Israel’

Inscription on the Merneptah Stele with the word ‘Israel’,

the oldest reference to Israel outside of the Bible text

A passage from the Merneptah Stele Inscription showing the word ‘Israel’ (this is the oldest reference to Israel in a text outside the Bible).

From 4th year of Pharaoh Merneptah (1212-1202 BC), possibly the pharaoh under whom the Exodus took place (his father Ramesses II may have been the pharaoh who enslaved the Israelites).

The passage reads as follows:

The Great Ones are prostrate, saying: “Peace” (shalama);

Not one raises his head among the Nine Bows;

Plundered is Thehenu; Khatti is at peace;

Canaan is plundered with every evil;

Ashkelon is conquered;

Gezer is seized;

Yanoam is made non-existent;

Israel is laid waste, his seed is no more;

Kharu has become a widow because of Egypt!

All lands together are at peace;

Any who roamed have been subdued.

The three characters on the left of the image above (woman, man, bent throwstick), along with the three vertical strokes beneath the first two, indicate that ‘Israel’ refers to a people, not a land or a city like Ashkelon, Gezer, and Yanoam.

In other words, Israel was a nomadic people in or near Canaan at the time this inscription was made.

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher