Gospel According to St Matthew * * * * *

Plot summary: The film is set in a rocky, barren landscape – no accident.

Jesus is a teacher and visionary. He’s stern, brusque, demanding. He comes to bring a sword, not peace.

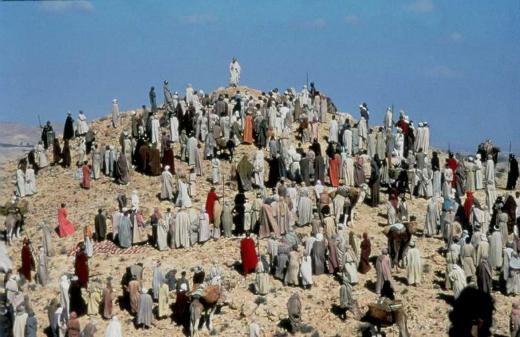

This is a man in a hurry, moving from place to place near the Sea of Galilee, sometimes attracting a multitude, sometimes being driven away. His parables often seem to criticise the powers that be, so he and his teachings come to the attention of the Pharisees, the chief priests, and elders. They conspire to have him arrested, beaten, tried, and crucified, just as he prophesied.

After he dies, he comes to his disciples and gives them final instructions.

What the critics said

The pregnant Mary of Nazareth

in Pasolini’s ‘Gospel According to St Matthew’

‘Pasolini’s Il Vangelo Secondo Matteo (The Gospel According to St. Matthew) was a strikingly unusual picturing of the story of Jesus, done with a cast of nonprofessionals on locations in southern Italy and directed by a man who was an acknowledged Marxist and atheist.

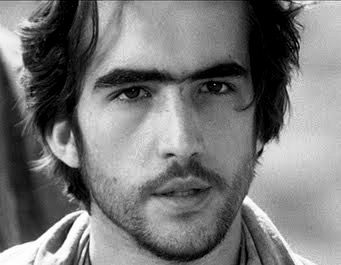

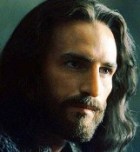

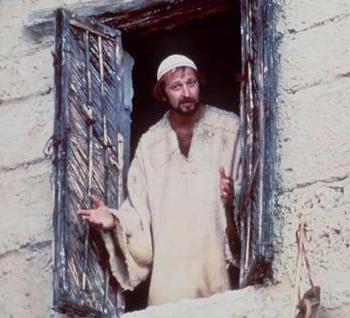

This time the story of Jesus is told in the simple and naturalistic terms of a plain man of the people conducting a spiritual campaign among a population that are rough, unadorned and real. The Jesus we see is no transcendent evangelist in shining white robes. He is a young man of spare appearance, garbed in dingy, homespun cloaks, moving with quiet resolution across a dusty countryside, gathering his tough-faced disciples from workers he meets along the way and preaching his words of exhortation to crowds of simple, sullen peasants and sprawling children.

The remarkable avoidance of clichés on Pasolini’s part — the simple staging of the Last Supper, for instance, as a gathering of a tired, disquieted group; the omission of the sound effect of a cock’s crow after Peter’s third denial—helps to achieve a fresh illusion of the unfolding of an ancient tragedy, or at least the illusion of the performance of a most reverent and sincere Passion Play.

It is impossible to give full credit to all the earnest performers, so many are they. But the Jesus of Enrique Irazoqui, a Spanish student who was visiting in Rome, is an unforgettable portrayal of fervor and sensitivity. Settimo Di Porto’s Peter is a fine, solid, foursquare man and Mario Socrate’s John the Baptist is a subdued firebrand in a poet’s angular frame.

Otello Sestili’s Judas, Paola Tedesco’s schoolgirl Salome and Susanna Pasolini’s older Mary, as well as Margherita Caruso’s Mary in her youth, are performances by unskilled actors that will engrave themselves on your mind.

The musical score is surprising. It has a distinct eclectic range from Bach’s St. Matthew’s Passion to “Missa Luba,” a Congolese mass sung to African intruments and rhythms.

Christ and his apostles in Pasolini’s ‘Gospel According to St Matthew’ To hear, for instance, Odetta sing the famous American Negro spiritual “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” behind scenes of Mary and the baby, (please click on this Youtube link: it’s one of the most beautiful things you’ll ever hear. Ed.) or the rousing “Alexander Nevesky Cantata” of Prokofiev behind Herod’s slaughter of the infants and the scene of Jesus’ removal to Golgotha may startle and disturb the placid ear. But these are just further surprises in a most uncommon film.’ (Bosley Crowther, New York Times)

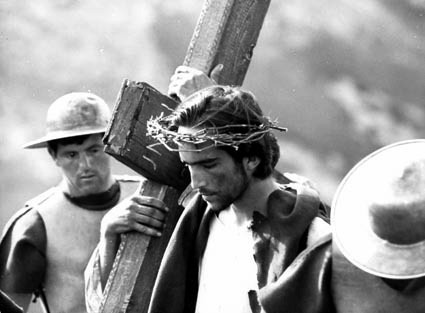

Comparing Pasolini’s film with The Passion of the Christ: There’s no question that The Passion of the Christ has affected some people profoundly, but that may be caused by the unfamiliar experience of seeing a mainstream film that rejects entertainment for serious inquiry and English for foreign tongues. If the film industry had more brains and more knowledge of cinema history, this audacious black-and-white 1964 masterpiece by the great Italian poet Pier Paolo Pasolini would be out in a major re-release right now as a meaningful alternative. Shot in southern Italy with a nonprofessional cast, and powerfully using both classical music and blues, this highly political interpretation of the Passion of Christ is as scandalous in its own way as Mel Gibson’s but more poetic, more contemporary in its impact, and more serious in its overall morality. (Jonathan Rosenbaum, Chicago Reader)

Christ carrying his cross

‘Its portrait of the Messiah – played by Enrique Irazoqui, a young Spanish economics student with a scraggy beard – is far harsher than the usual soft saint that passes for Jesus. The actor wears no make-up and nor does the rest of the cast. Judas is played by a truck-driver from Rome (Otello Sestili), and Pasolini’s own mother is the Virgin Mary. They are all amateurs, and the close-ups of their faces make the story seem more real than usual. The bleak hillside scenery of Calabria, where the film was made, gives the film a primitive feel that is augmented by grainy cinematography. What Pasolini clearly wanted was a believable gospel, armed with real people.

It is a stark film (someone has described it as one-dimensional), but with clear-headed qualities that avoid the usual clichés. This Christ was a political animal, angry at social injustice. The silent cry from the cross is believable and the miracles avoid any kind of underlining comment – they just happen, with not a special effect in sight.’

Ten Commandments * * * *

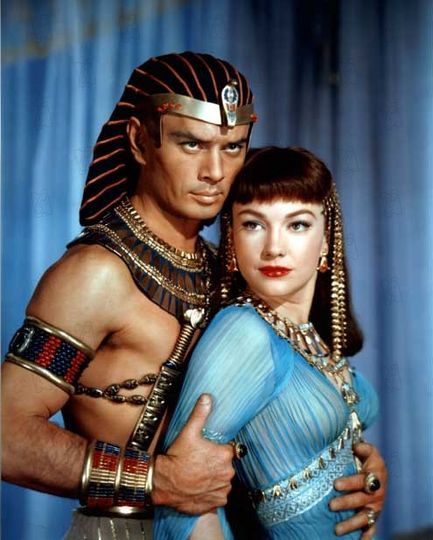

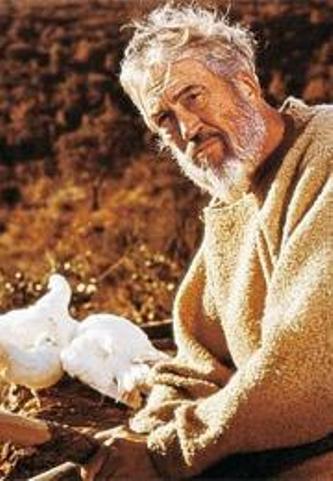

The Pharaoh Seti in

The Ten Commandments

Click for a scene from the movie

Plot summary: In ancient Egypt the Pharaoh Seti becomes fearful of the Hebrew slaves and orders that all their newborn male babies be killed. To save her baby, a Hebrew mother weaves a reed basket and sets her infant son adrift on the waters of the Nile. He is found and saved by the pharaoh’s daughter Bithiah, then brought up in the royal court. Moses is capable and intelligent, and gains Seti’s favor and the love of the throne princess Nefertiri, as well as the hatred of Seti’s son, Rameses.

When his Hebrew heritage is revealed, Moses is cast out of Egypt, and makes his way across the desert where he marries, has a son and is commanded by God to return to Egypt to free the Hebrews from slavery. He reluctantly returns to take on what he thinks is an impossible task, but is helped by God’s power (and the Ten Plagues) to prise the Hebrews away from Pharaoh’s grasp (Click here for this scene). They flee from Egypt, are pursued, escape, doubt God’s power and eventually reach the Promised Land.

What the critics said

‘According to Jesse L Lasky Jr, he and his fellow-writers ‘felt so inoculated with significance that we hardly dared write at all, certainly not with such profane tools as pencils and typewriters’.

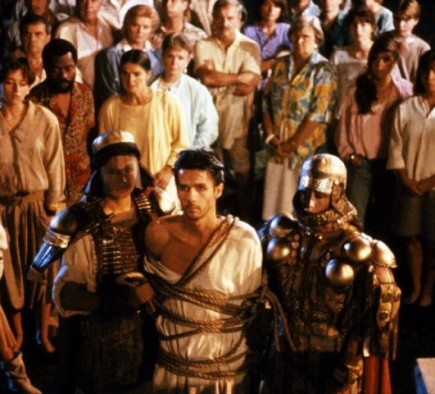

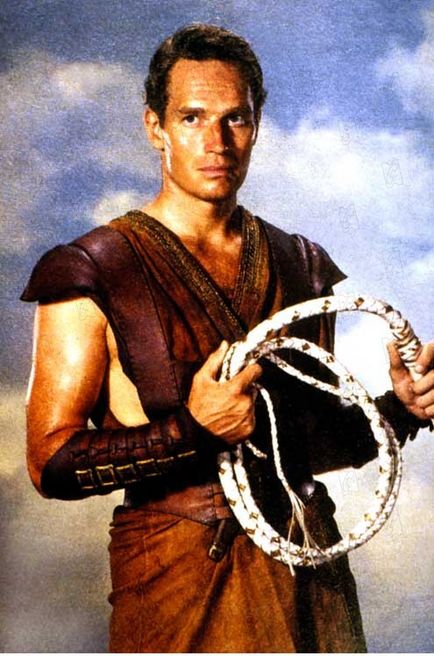

Moses as an Egyptian Prince

in ‘The Ten Commandments’

The Ten Commandments won’t be remembered as literature – the script is a sort of prose doggerel Biblespeak of unerring shallowness; or for its acting, with only Edward G Robinson and Hardwicke emerging as more than pawns in DeMille’s vast game. Rather it’s the gigantic vulgarity, the obsessive righteousness of the director himself, which keeps the show on the road and suffuses the movie with its daft power.

There are two wondrous scenes. The exodus itself, gigantic aerial shots of the DeMillions underpinned by meticulous detail, is a genuine mover. The other goodie, surprisingly, is a dialogue scene in which Hardwicke, confronted by an enchained Heston, hands the succession (and Anne Baxter as a smouldering bonus) to Brynner. Most of the rest is arid nonsense a mile high. But you have to admire DeMille’s seriousness of purpose. He took three weeks on the orgy scene alone.’

Yul Brynner and Anne Baxter in ‘The Ten Commandments’

‘With a running time of nearly four hours, Cecil B. De Mille’s last feature and most extravagant blockbuster is full of the absurdities and vulgarities one expects, but it isn’t boring for a minute. Although it’s inferior in some respects to De Mille’s 1923 picture of the same title (which used the story of Moses as an extended prologue to a contemporary tale) and some of the special effects look less plausible now than they did in 1956, the color is ravishing, and De Mille’s showmanship, which includes a personal introduction and his own narration, never falters.

Simultaneously ludicrous and splendid, this is an epic driven by the sort of personal conviction one almost never finds in more recent Hollywood monoliths. (Jonathan Rosenbaum, Chicago Reader)

‘DeMille took a lot of flack from studio executives who thought that the Biblical epic was a tired genre. The studio wanted the legendary director to work with more marketable material. What a loss that would’ve been, as this supreme epic remarkably stands up over time despite its stylized choreography, touches of melodrama, and unintentionally funny dialogue flourishes. Many continue to love it and religiously watch its traditional Easter showing on television for its melodramatic delineation between good and evil that comes directly from the silent era. Elmer Bernstein’s indulgent score completes the old style drama by overtly announcing the good and evil characters as they appear. You can almost sense the audience alternately cheering and hissing.

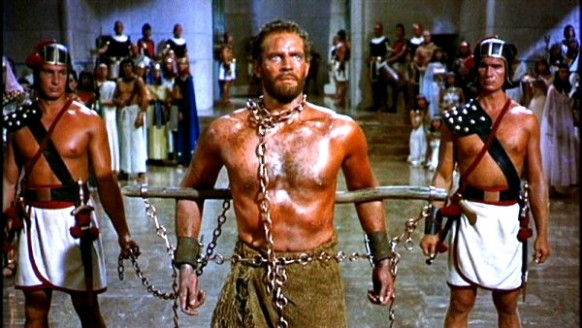

Charlton Heston as Moses confronts his Hebrew identity

The overdone dialogue also is a treat. Everybody repeats “Moses, Moses” whenever addressing him, including Pharaoh Sethi (Sir Cedric Hardwicke) on his deathbed despite previously ordering that the name “Moses” be erased from the memory of man for all time.

Funniest are Nefretiri’s (Anne Baxter) numerous flirtations (“Oh Moses, Moses, you stubborn, splendid, adorable fool!”) that betray her obsessive lust and propel the plot forward. Nefretiri uses her sexual favors to get the jealous Ramses to do whatever she wants, whether manipulating him to give Moses a break or belittling him for allowing the Hebrew slaves to go.’

The Ten Commandments. Moses in chains at the court of the Pharaoh

‘The Ten Commandments‘ is BIG. With the largest sets ever designed, filmed both on location in Egypt and Sinai and on the Paramount back lot, DeMille literally directs a cast of thousands with the generous help of the Egyptian army as extras, organizing the grandest production of the first half century of filmmaking. A Bible scholar, DeMille took great pains during pre-production to recreate the period as accurately as possible—only taking cinematic liberties for dramatic purposes. A few examples:

- Purposely leaving out colorful interior palace murals so that they don’t dominate the cast.

- Not allowing Moses to stutter as described in Exodus. It wouldn’t be fitting to have the hero stand by silently as his brother Aaron delivers the message.

- Only hinting at Moses’ marriage to an African, as a direct reference would be too challenging to fifties audiences.

The Parting of the Red (Reed) Sea in ‘The Ten Commandments’

Turning the Nile into blood remains one of the great moments in epic films, particularly when Ramses’ attempts to purify the river from a sacred vase are thwarted. The fiery hail (achieved by popcorn and sound effects) and the foggy green pestilence that claims Egypt’s first born are also rendered with suspense and continue to mesmerize, all without CGI assistance.

Although the plagues are really well conceived, the scenes that everyone remembers are the great set pieces: the Exodus from Egypt, the parting of the Red Sea, and God’s revelation of the Law. DeMille tirelessly worked with numerous bit players in the large crowd scenes, so that everyone has specific tasks to do and marks to hit. Those all make up for the disappointing burning bush, only notable because the voice of God is actually Heston (deepened and distorted). Moses smashes the stone tablets in ‘The Ten Commandments’

Although it’s easy to poke holes in DeMille’s The Ten Commandments, there’s good reason that it remains one of cinema’s best-loved classics. Yul Brynner was never better and makes us believe that he really comes from Egyptian royalty, and Charlton Heston carves out a true religious iconic role as Moses.

In the highly choreographed world of Cecil B. DeMille, Heston turns in a perfect performance for Moses (despite a final scene with really lame whitened beard and make-up with hands that somehow retain their youth).

Ask anyone what image forms when they think of “God” and “Moses,” and you can pretty much bet that most people will be thinking of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel and a scene from The Ten Commandments.’ (John Nesbitt, Old School Reviews)

Save

The Passion of the Christ * * * *

Plot summary: We see the last twelve hours of Jesus’ life, just before he is crucified. Jesus prays in the Garden of Olives after the Last Supper. He is betrayed by Judas, arrested by soldiers and hauled back into Jerusalem. Here he is confronted by the leaders of the Pharisees, a powerful political/religious group, who accuse him of blasphemy and suggest the death penalty. Jesus is then taken to Pontius Pilate, the Roman Governor, for sentencing. Pilate, in an effort to pass the buck, defers to King Herod in deciding the matter. But Herod is no fool. He returns Jesus to Pilate who allows the crowd outside his palace to decide. The crowd chooses death for Jesus, who is handed over to the Roman soldiers and brutally beaten.

Plot summary: We see the last twelve hours of Jesus’ life, just before he is crucified. Jesus prays in the Garden of Olives after the Last Supper. He is betrayed by Judas, arrested by soldiers and hauled back into Jerusalem. Here he is confronted by the leaders of the Pharisees, a powerful political/religious group, who accuse him of blasphemy and suggest the death penalty. Jesus is then taken to Pontius Pilate, the Roman Governor, for sentencing. Pilate, in an effort to pass the buck, defers to King Herod in deciding the matter. But Herod is no fool. He returns Jesus to Pilate who allows the crowd outside his palace to decide. The crowd chooses death for Jesus, who is handed over to the Roman soldiers and brutally beaten.

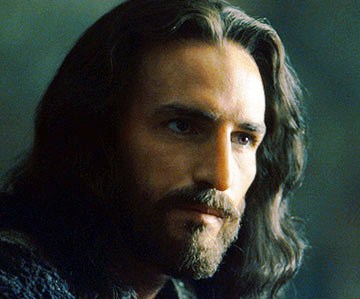

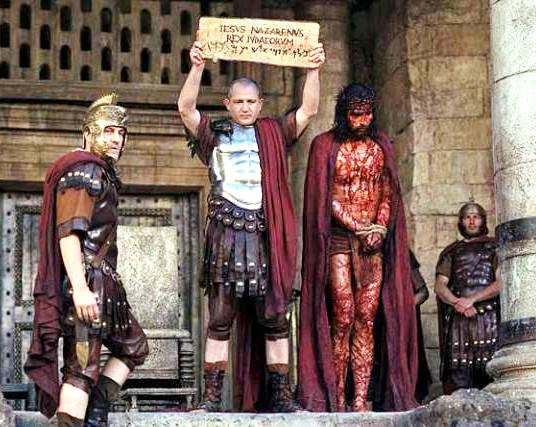

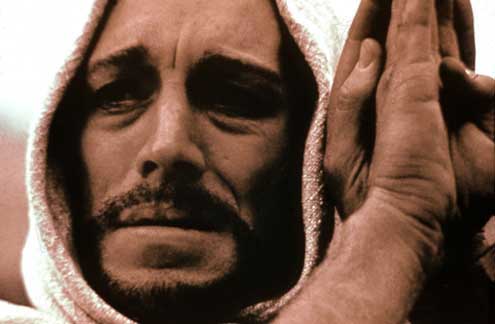

Jesus in ‘The Passion of the Christ’,

Last Supper scene

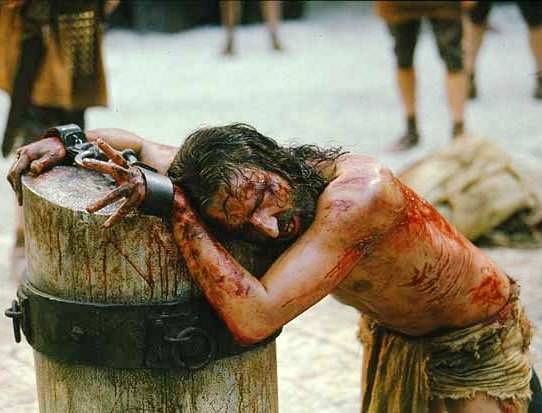

Bloody and unrecognizable, Jesus is taken back to Pilate who washes his hands of the entire dilemma, ordering his men to do as the crowd wishes. Whipped and weakened, Jesus is forced to carry the cross for his own crucifixion through the streets of Jerusalem to Golgotha. There, the hideous process of crucifixion is carried out. Jesus is left to die of asphyxiation, blood loss and shock. Jesus speaks his last words and dies, amid a tumultuous reaction by Nature.

What the critics said

‘…this is simply one of the most powerful movies I have ever seen. James Caviezel stars in the role of Jesus Christ, and his performance is incredible. He literally breathes the role of Christ in this movie. He reportedly experienced a good deal of pain himself during the filming of The Passion in the form of being struck by lightning, being accidentally whipped, and experiencing frostbite and pneumonia.

Mary, mother of Jesus of Nazareth, in ‘The Passion of the Christ’

The two Marys (Bellucci and Morgenstern) are portrayed as spectators to Jesus’ death. After the gut-wrenching scourging scene, Mary (Jesus’ mother) slowly walks over and begins to clean up Jesus’ blood with a towel. I found this to be one of the most touching scenes in a very touching movie. Gibson has also included his vision of Satan, played by Rosalinda Celentano as an androgynous being that lingers in the background of several of the film’s crucial scenes.

The Passion of the Christ emerges from all of the hype and controversy as one of the best films in recent years. It will no doubt be analyzed and talked about for the foreseeable future. It will also undoubtedly leave a lasting impression on most who see it with its brutality, setting, and interpretation of “The Greatest Story Ever Told.” This is highly recommended viewing for those who are old enough and those who have strong stomachs. You will be seeing one of the best films of this decade.’ (Bill Clark, From The Balcony)

Jesus is scourged by the Roman soldiers

‘The film’s violence has been defended as a sign of its historical realism and biblical accuracy, but one of the more striking and impressive things about The Passion is just how much artistic license it takes with its source material. Gibson erroneously identifies Mary Magdalene (Monica Bellucci) with the woman caught in adultery, and his depiction of the Crucifixion owes more to medieval art than modern scholarship. Taking their cue from historians and archaeologists, nearly every film and miniseries produced since the 1970s has depicted Jesus carrying only a crossbeam, being nailed through his wrists, being crucified naked, or some combination thereof. Gibson rejects all of these details, though he does, oddly, have the thieves carry crossbeams, while Jesus carries his full cross.

Gibson does embrace at least one welcome form of realism by emphasizing the Jewishness of Jesus and his followers. Caviezel has been made up to look more Semitic, and the first time we see Mary, as she senses that something terrible is about to happen to her son, she recites a line that comes straight from the Passover seder: “Why is this night different from every other night?”

Pontius Pilate (Hristo Shopov) comes off as an innocent pawn who tries to do the right thing until the mob forces his hand.

Pontius Pilate shows Jesus to the crowd

The real villain in Gibson’s film, however, is no mere human. Satan (Rosalinda Celentano) is depicted here as a bald, pale, androgynous figure who lurks in the crowds and taunts Jesus at every turn—and it is in his bold, haunting, and audacious depiction of Satan that Gibson’s vision turns truly surreal. In Gethsemane, Satan prods Jesus to doubt his Father and sends a snake slithering his way, which Jesus quickly crushes underfoot. Later, Satan mocks Jesus’ mother in a bizarre parody of Marian iconography that could have come from David Lynch. Satan is also absolutely ruthless with Judas (Luca Lionello), who is driven to suicide by seemingly demonic beasts and children. And—who knows?—Satan may even be behind the crow that pecks out the eyes of the crucified thief who mocks Jesus.

Mary Magdalene

Gibson also makes brilliant use of flashbacks to draw us into the mind of Christ. Most movies about Jesus protect his divinity by treating him objectively, as someone to be observed and talked about, but not as someone with whom we can identify. Productions like Martin Scorsese’s Last Temptation of Christ and the CBS miniseries Jesus have tried to humanize Jesus by treating him more subjectively—we see his dreams, we hear his thoughts in voice over, and we get inside his head the same way we do with many other movie characters.

Where those films failed, partly because they demystified Jesus so thoroughly that he seemed to lose his divine authority, Gibson succeeds by shooting much of the film from Jesus’ point of view and by using flashbacks to create the impression that we are being drawn into Jesus’ own memories. When Jesus sees a man with carpentry tools, he thinks of his days as a carpenter; when he sees the street filled with people shouting at him, he thinks of his Triumphal Entry a few days before; when he sees Golgotha, he thinks of the sermon he gave on another mountain in which he told his followers to love their enemies. (Peter Chattaway, Christianity Today)

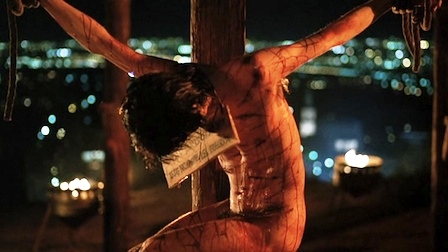

Jesus of Nazareth on the cross

Jesus of Montreal * * *

Crucificion Scene

Youtube link

Jesus of Montreal – the full movie

Plot summary: Daniel Coulombe (Lothaire Bluteau) is engaged by a Montreal priest to improve on the parish’s tired passion play. He is quietly excited by the possibility and invites a group of old friends to join him in revitalizing the ancient tale. They will stage the performance outside by torchlight on the crest of Mount Royal with the lights of the vast city flickering below. The script is modern, visceral, and engages the audience. The actors all manage to improve their life situations if not their finances: a man gives up dubbing scripts for porno movies; a woman leaves an abusive partner to become the Magdalene.

At first, the priest is pleased by their efforts, but he looses credibility when Coulombe finds he sleeps with one of the women actors. The play is a huge success, but nameless clerical authorities are disturbed by the vibrant sexuality and the avant garde performance; in the absence of support from the priest, “they” revoke the right to perform.

The defiant troupe performs anyway, hoping the police will be sympathetic. A naked Coulombe is arrested off the cross in the midst of his crucifixion scene. A scuffle ensues and he suffers an accidental head injury. Taken by ambulance to a busy hospital, he is neglected, but recovers enough to sign himself out, only to collapse in a subway station. Attended by the two dismayed and disoriented women, he is again taken to hospital where he dies. (From NYU Literature, Arts and Medicine Database)

What the critics said

Jesus brought to trial in ‘Jesus of Montreal’

‘Denys Arcand’s intelligent, audacious Jesus of Montreal attempts to shake up stale religious assumptions, and for the first hour, before it gives in to leaden, self-conscious Christ imagery, the film succeeds. The actor who is hired to play the lead and revise the Passion play at a Montreal shrine looks too traditional a Jesus, with a perpetual mournful expression. The film works best when he still seems human, before Arcand merges Daniel with Christ.

As the film weaves in and out of the characters’ lives and their new version of the Passion, Arcand loses the wily, contemporary grip that makes his material effective. ”Jesus of Montreal” starts out as a mix of Martin Scorsese’s historically set ”Last Temptation of Christ” and ”The Ruling Class,” a satire in which Peter O’Toole is an English aristocrat who believes he is Jesus. But midway through, it turns into ”The Greatest Story Ever Told” set in urban Montreal. Even a Christ figure needs more of an interior life than Arcand gives Daniel. ”Jesus of Montreal” is finally not radical enough.’ (Caryn James, New York Times)

Denys Arcand’s “Jesus of Montreal” suffers from a lethal case of Block That Allegory. Structured to follow the Stations of the Cross, the film is a satirical bouillabaisse with the Church, the theater and modern advertising as some of its topics. It features its own uncompromising, self-aggrandizing Christ, a Mary Magdalene who walks on water (through the magic of special effects) to sell perfume, even an entertainment lawyer who devilishly tempts the actor Christ with a variety of methods for cashing in on his success, including attaching his name to a cookbook.

Jesus hanging on the cross in ‘Jesus of Montreal’

“Jesus of Montreal” is a movie from a director with intelligence and refined sensibilities – the Canadian’s best-known work is “The Decline of American Civilization.” In fact, it’s entirely possible that his sensibilities are too rarefied. The variations on the Christ story are never less than clever, sometimes quite damningly so. But they’re labored too and, on occasion, painfully obvious.

The early scenes, in which Daniel makes his casting rounds, parallel the biblical scenes in which Christ meets His disciples, and they’re the movie’s best. As he collects his collaborators, Daniel begins to feel his way into the Christ character, and we can see the messianic gleam in his eye as he examines the historically accurate drawings of crucifixions. Bluteau is one of Canada’s most respected actors, and with his narrow shoulders and fragile, elongated face, he seems perfectly suited to his role. But there’s a kind of mopeyness to this Christ; he looks as if what he needs is a nice, long nap. Bluteau lacks fire, and in his scenes with other actors, your eye wanders away from him. He seems anything but the charismatic spiritual leader and the object of obsessive devotion and love.

The dead Jesus and Mary Magdalene in a subway station

The rest of the cast is accomplished, but aside from Catherine Wilkening’s Mireille (the Mary Magdalene character), none of the characters is allowed to blossom. Guy Dufaux’s shots of Montreal give the film an away-from-the-world feel. But Arcand’s ideas suffer as much from isolation as the culture he pokes fun at; they seem oddly out of date, as if the film had sprung straight from the heart of the ’80s. Once the play is staged — Arcand makes the mistake of showing us the whole thing — the picture comes to a dead stop and never quite gets going again. Still, Daniel’s martyrdom and eventual resurrection are inspired — so much so that it makes you wish the rest of the film had been on that level.’ (Hal Hinson, Washington Post)

The Bible * * *

Plot summary

This film is an elaborate retelling of the first section of the Book of Genesis, from the creation of the world to the time of Abraham. We open with the ‘In the beginning’ events and the first seven days, then move to the Garden of Eden with Adam and Eve. This leads to the appearance of Cain and Abel and the subsequent murder of Abel. Next, we visit Noah and his ark with its spectacular flood sequence. Then we come to the story of Nimrod, King of Babel, the emergence of man’s vanity and the heights to which it would go if unchecked. Finally Abraham appears, a mystic who spoke personally with God, and a visionary leader of his tribe. His beautiful but barren wife is Sarah, who gives her slave Hagar to Abraham to bear him a son. Later, against the odds, Sarah conceives her first child, the event being forecast by three heavenly messengers. The film ends with the near sacrifice of Isaac, beloved son of Abraham, and the boy’s last-minute reprieve.

Adam and Eve meet each other for the first time in ‘The Bible’

What the critics said

‘THE big motion picture called The Bible begins with the uproar of Creation, which goes on for perhaps a half hour, and the emergence of Adam and Eve as the first humans, fully grown, cleanly washed and luminously blond. It continues with Eve eating the apple from the Tree of Knowledge at the behest of a snake and being cast by the Lord from the Garden of Eden, along with Adam, for disobeying His command.

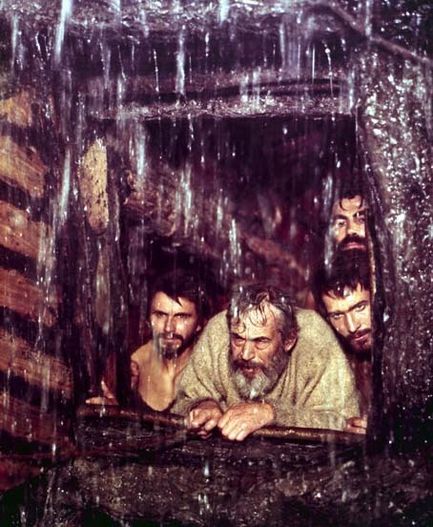

Noah and his sons peer out from the Ark in ‘The Bible’

For all its size, for all its extravagant production and its almost three-hour length, “The Bible” is lacking a sense of conviction of God in so much magnitude or a galvanizing feeling of connection in the stories from Genesis. Where is the feel of faith and wonder in so much spectacle, where is the mounting of illusion that this is the consequence of a divine creative will? Certainly it comes not from seeing a naked young man emerge in a slow dissolve from a small mound of lemon-colored dust, while Toshiro Mayuzumi’s music groans grotesquely and Huston’s off-screen voice intones. “So God created man in His own image, in the image of God created He him.”

Nor does it come from idyllic glimpses of the naked young man and girl (Michael Parks and Ulla Bergryd) ambling mutely through verdant glades, or from wild shots of Cain (Richard Harris) suddenly slaying his astonished brother in a field, again with Huston narrating what is happening in the words of the St. James’s Bible.

It comes, if at all—and only faintly—in the way Mr. Huston plays Noah. (Yes, he plays Noah as well as directs the picture and furnishes the off-screen voice of God). He plays the primordial shipbuilder as a rustic, cloth-robed patriarch—a little bit of a crackpot, a little bit of a clown and a great deal of a man of simple, unswerving faith.

John Huston as Noah in ‘The Bible’

You can almost believe that this old fellow is tuned in on the voice of God, just as you can believe that susceptible children listen to Peter Pan. And when Noah shepherds his family together to build the freakish ark, marshals the circus parade of animals into the hangar-deck (digressing to hurry up the turtles or to gawk in wonder at the giraffes) or busies himself with the burdens of keeping the animals fed, you do feel a certain spiritual presence and sense the meaning of trust in the Lord.

Likewise, there is a feel of fervor in the stern-faced intensity with which George C. Scott brings the patriarchal person of Abraham to the screen. But his is a chill, forbidding figure, egocentric and aloof, without warmth even in his concubinal encounter with the handmaiden, Hagar (Zoe Sallis), or in his biological discussions with Sarah, his wife. Scott and Ava Gardner play the couple as though they were posing for monuments.

Something warm and mysterious comes, however, from the brief dialogic scene in which Abraham is visited by the Three Angels, all played symbolically by Peter O’Toole. From this confrontation comes the strongest feeling in the film of human minds searching for answers in the mystical presence of God.

But there’s too little of this in the picture, and that’s the fault of the script by Mr. Fry. It relies upon literal enactments and the sheer sonority of holy writ. And when it tries for a bit of commentary, such as having Lot’s wife turn to salt on looking back on the destruction of Sodom and seeing a rising atomic mushroom cloud, the significance of the symbolism is puzzling, if not imponderable. (I wonder if Mr. Fry is truly saying what my cynical mind guesses he is?)

Anyhow, the misfortune of “The Bible” is that it does not live up to hopes. It does not employ the cinema medium to create a true 20th-century iconography. It simply repeats in moving pictures what has been done with still pictures over the centuries. That is hardly enough to adorn this medium and engross sophisticated audiences.’ (Bosley Crowther, New York Times)

Ben Hur * * * * *

Plot summary: It is the seventh year of Augustus Caesar’s reign. In the Roman province of Judea, Jews return to the city of their birth for the census. A bright star in the night over Bethlehem marks the birth of Jesus Christ. Years later, Roman commander Messala (Stephen Boyd), who was brought up in Judea, takes command of the Roman garrison in Jerusalem. His Jewish boyhood friend Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston) greets him. Messala is delighted. But when Judah refuses to name Jewish patriots, Messala sentences him to the slave galleys and imprisons his mother, Miriam (Martha Scott), and sister, Tirzah (Cathy O’Donnell). Judah vows revenge.

Ben Hur (Charlton Heston) as a charioteer

in the film ‘Ben Hur’

Ben Hur (Charlton Heston) as a charioteer in the film ‘Ben Hur’ The story of Judah’s search for his mother and sister, and his quest for revenge, intersects with crucial biblical events such as the Sermon on the Mount and the crucifixion. Director William Wyler gets fine performances from Heston, Boyd, Jack Hawkins (as a Roman admiral who befriends Judah), and Hugh Griffith (as an Arab sheik who dreams of racing his beautiful white horses against Messala). Among the vivid dramatic sequences are a violent sea battle and the famous chariot race that pits Judah against Messala in one of cinema’s great action sequences.

What the critics said

‘Without for one moment neglecting the tempting opportunities for thundering scenes of massive movement and mob excitement that are abundantly contained in the famous novel of Lew Wallace, upon which this picture is based, Wyler has smartly and effectively laid stress on the powerful and meaningful personal conflicts in this old heroic tale. As a consequence, this mammoth color movie is by far the most stirring and respectable of the Bible-fiction pictures yet made.

This is not too surprising, when one considers that the drama in Ben-Hur has a peculiar relevance to political and social trends in the modern day. Its story of a prince of Judea who sets himself and the interests of his people against the subjugation and tyranny of the Roman master race, with all sorts of terrible consequences to himself and his family, is a story that has been repeated in grim and shameful contexts in our age.

Massala, once Ben Hur’s great friend

but now his deadly enemy in the film ‘Ben Hur’

This theme is grippingly conveyed in some of the most forceful personal conflicts ever played in costume on the screen. Where the excitement of the picture may appear to be in the great scenes, such as those of the ancient sea battle in which Ben-Hur is involved as a galley slave or those of his final contention with Messala, the Roman tribune, in a mammoth chariot race, the area of fullest engrossment is the scenes of people meeting face to face—Ben-Hur verbally clashing with Messala, a Roman soldier suddenly looking upon Jesus.

Wyler’s big scenes are brilliant and dramatic—that is unquestionable. There has seldom been anything in movies to compare with this picture’s chariot race. It is a stunning complex of mighty setting, thrilling action by horses and men, panoramic observation and overwhelming dramatic use of sound. But the scenes that truly reach you are those that establish the sincerity and credibility of characters. Ben-Hur’s encounters with his mother and his sister, who later become lepers, or his passing meetings with Jesus (who is never viewed in full face) are dignified and true. Likewise, the enactment of the Crucifixion is impressively personal, strong and real. It is not done in an aura of gauzy reverence but has the nature of a dark political deed.

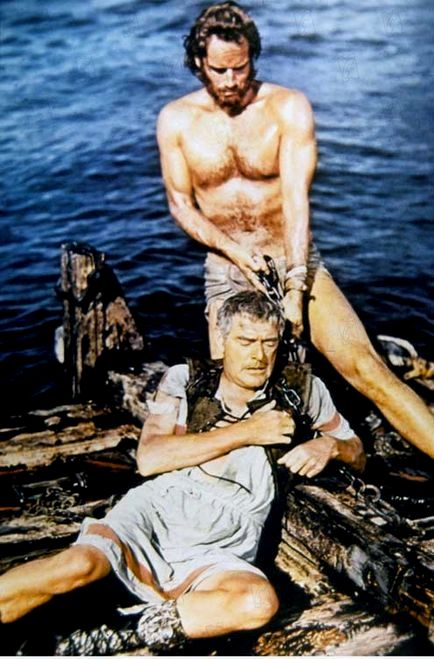

Ben Hur saves a Roman aristocrat from drowning at sea in the film ‘Ben Hur’

Charlton Heston is excellent as Ben-Hur—strong, aggressive, proud and warm—and Stephen Boyd plays his nemesis, Messala, with those same qualities inverted. Jack Hawkins as the Roman admiral who fatefully makes Ben-Hur his foster son, Haya Harareet as the Jewish maiden who tenderly falls in love with him, Hugh Griffith as the sheik who puts him into the chariot race and Sam Jaffe as his loyal agent—these also stand out in a very large cast. (Bosley Crowther, New York Times)

‘Ben-Hur is a classic revenge epic leavened with a pious message of forgiveness. Charlton Heston stars as Judah Ben-Hur, a Jewish prince whose boyhood friendship with a Roman officer named Messala (Stephen Boyd) turns to enmity over politics and betrayal. (In his autobiography Heston reports that although screenwriter Gore Vidal was let go after trying to imbue a homoerotic subtext into Judah and Messala’s relationship, Boyd’s performance in early scenes seems to reflect Vidal’s influence. At least if that element is there, it’s embodied by the pagan Roman villain, not the righteous Jewish hero.)

The starters line up for the great race in the film ‘Ben Hur’

The sheer scale of the picture, in the days before digitally created crowds and computerized process shots, is astounding. The central set piece, the classic chariot race, remains a brilliant action sequence, with Heston and Boyd doing their own riding and nearly all their own stunts.

Although not a spiritually profound film, Ben-Hur does include a strikingly evocative image of Christ’s redemptive death: Jesus’ blood pools at the foot of the cross and, mixed with the rainwater from a sudden deluge, runs down the mountain and over the land, touching the feet of Judah Ben-Hur as he walks unknowingly by.’ (Steven D Greydanus, National Catholic Register)

Ben Hur and his white chariot horses lead the race in ‘Ben Hur’.

‘Everything about Ben Hur was enormous; more than 300 sets were employed, covering more than 340 acres. The arena housing the chariot race consumed 18 acres, the largest single set in film history. The five-story stands were packed with 8,000 extras, and 40,000 tons of sand were taken from beaches to make the track. Scores of Yugoslavian horses were imported for the spectacular 20-minute race, which took three months to shoot. More than 1000 workers labored for a year to build the colossal arena. Rome’s Cinecitta Studios were gutted of more than a million props, and sculptors made more than 200 giant statues. Also unique were the wide-screen cameras employed, 65 millimeters wide, to achieve sharp, deep focus. MGM lavished about $12,500,000 on this stupendous production, which brought them near bankruptcy, but the returns were staggering: a gross of $40 million.’ (TV Guide)

The Robe * * * * *

Marcellus and Diana confront Caligula

Plot summary: Marcellus is a tribune in the time of Christ. He is in charge of the group that is assigned to crucify Jesus. Drunk, he wins Jesus’ homespun robe after the crucifixion. He is tormented by nightmares and delusions after the event. Hoping to find a way to live with what he has done, and still not believing in Jesus, he returns to Palestine to try and learn what he can of the man he killed.

What the critics said

The Robe was 10 years coming, and it is a big picture in every sense of the word. One magnificent scene after another unveils the splendor that was Rome and the turbulence that was Jerusalem at the time of Christ on Calvary.

Jean Simmons as Diana in ‘The Robe’

The homespun robe worn by Jesus is the symbol of Richard Burton’s conversion when the Roman tribune realizes he carried out the crucifixion of a holy man at Pontius Pilate’s orders. Victor Mature is the Greek slave for whom Burton outbid the corrupt Caligula (Jay Robinson). Jean Simmons is cast as the love interest who, as the ward of the Emperor Tiberius, spurns her destiny as Caligula’s betrothed for the love of Marcellus Gallio (Richard Burton).

The performances are consistently good. Simmons, Burton and Mature are particularly effective, and the sword duel between Jeff Morrow’s heavy and Burton is a highlight.

The slave market, the freeing of the Greek slave from the torture rack, the Christians in the catacombs, the dusty plains of Galilee, the Roman court splendor and that finale ‘chase’ (with the four charging white steeds head-on into the camera creating a most effective 3-D illusion) are standouts. (Variety)

Marcellus (Richard Burton) is present

at the crucifixion of Jesus in ‘The Robe’

Fighting for fashion, in widescreen no less. A heavy Biblical dirge, bulging with blandfilmitis bigbudgetitis, The Robe was the first film in CinemaScope, Hollywood’s answer to the threat of TV. Audiences (primarily Catholic school children dragged kicking and screaming by their teachers) dutifully poured into theaters to watch orgy-weary Roman officer turned luminous Christian Richard Burton (very stiff in a part he considered prissy and silly) and his equally shiny and suffering co-star Jean Simmons (who deserved better) fight for a bolt of cloth that J.C. wore before his death.

Their opponent is evil emperor Caligula (Jay Robinson, in a flamboyant camp classic performance that must be seen to be believed). Luckily, Dick and Jean, who have an unfortunate date with death, have Demetrius (the Mature Vic, giving the film’s best performance) on their side. He rescues the rumpled but revered wrap just in time to tote it with him to the sequel, Demetrius and the Gladiators, where he must face a more dangerous lioness than any Caligula ever kept penned up: Susie Hayward. Stick with The Ten Commandments. (TV Guide)

Recommendation: don’t listen to the critics. Watch the movie for yourself. It’s an oldie but a goodie.

Save

Greatest Story Ever Told * *

Plot summary: This film covers events during the three-year ministry of Jesus of Nazareth, up until his death and resurrection. Click HERE for this movie’s Resurrection scene.

What the critics said

‘By staging the story of Jesus against the vast topography of the American Southwest and mingling the mystical countenance of Max von Sydow, the Swedish actor, with a sea of familiar faces of Hollywood stars, the producer-director George Stevens has made what surely is the world’s most conglomerate Biblical picture in “The Greatest Story Ever Told.”

There are things of supreme and solemn beauty in this almost four-hour-long color film. There are scenes in which the grandeur of nature is brilliantly used to suggest the surge of the human spirit in waves of exaltation and awe. And there are sections that develop sharp perceptions of the conflict between the evangelism of Jesus and the political powers of the day in Palestine.

The anguished face of Christ in ‘The Greatest Story Ever Told’

But there are also annoying excursions into large-screen theatricality that contort some of the events in the career of Jesus into encounters that look extravagant and gross. There are too many scenes in which the preaching of Jesus to the disciples and to the multitudes is so drawn-out and repetitious that it becomes monotonous.

And most distracting are the frequent pop-ups of familiar faces in so-called cameo roles, jarring the illusion of the moment. Most shattering and distasteful of these intrusions are the appearances of Carroll Baker and John Wayne in the deeply solemn and generally fitting enactment of the scene of Jesus carrying the cross to Calvary. Suddenly, at a most affecting moment, the plump-cheeked Miss Baker appears as a woman of the streets (Veronica) to wipe the sweat from Jesus’ face. And right at a point of piercing anguish, up pops the brawny Mr. Wayne in the costume of a Roman centurion. Inevitably, viewers whisper, “That’s John Wayne!”

Mary of Nazareth, mother of Jesus,

in ‘The Greatest Story Ever Told’

There is very little simple realism in this massive Passion Play. Virtually everything is given huge proportions on the screen. Thus the scene of the Wise Men being guided by the star to Bethlehem is a brilliantly blue-white illustration that resembles a handsome Christmas card. The period of Jesus’ temptation — his trial in the wilderness—is symbolized by a long and painful sequence of his climbing a rocky mountainside that becomes more precipitous and difficult as he ascends. On the way up, he stops in the cave of a hermit—a devious rascal, played by Donald Pleasence—who makes him an ambiguous offer of being master of the world. The mouth of the cave is virtually filled by the image of an outsized full moon, which bears on its face the seeming profiles of continents on the earth.

So chary is Stevens of showing the working of miracles that he has only two in the picture—until the Lazarus episode. These are the curing of the lame man (called Uriah, played by Sal Mineo) and the giving of sight to the blind man (called Old Aram, played by Ed Wynn.) Both may be regarded as not uncommon medical phenomena. Even in the episode of Lazarus, it appears until the end that the miracle may be a hallucination of the on-looking crowd.

The Last Supper in ‘The Greatest Story Ever Told’

Sidney Poitier’s Simon of Cyrene, the African Jew who helps carry the cross, is the only Negro conspicuous in the picture and seems a last-minute symbolization of racial brotherhood.

At the end, one may feel that almost four hours is too long a time to devote to a far-from complete dramatization of the last three years of Jesus’ life. But Stevens has done it in a generous and often stunning style. And the quality of his reverence should captivate the piously devout.’

(Bosley Crowther, New York Times)

Life of Brian * * * *

Plot summary: Essentially the story is about Brian. At birth mistaken by three wise men for the Son of God, his mother raises him to believe that his father was a certain Mr Cohen. But it seems that his father was in fact a Roman centurion, one Naughtius Maximus. Horrified, Brian decides to join a rebel group, the Peoples’ Front of Judea (not to be confused with the Judean Peoples’ Front). The presence of Judith in this group is another incentive. The group plans to kidnap Pilate’s wife, but their mission goes astray with unforeseen consequences, Brian being mistaken for the Messiah. But as we all know, he’s not the Messiah.

What the critics said

A well-meaning sermon in ‘The Life of Brian’

Following the star, the Three Wise Men make their way across the desert to the manger to adore the newborn babe, tended by his mum, a snaggle-toothed crone named Mandy. Until they produce their gifts, Mandy will have none of the Three Wise Men, whom she takes for fortunetellers. Mandy grabs the gold and the frankincense but is suspicious of the myrrh. “What is myrrh?” she asks with a sniff. “It sounds like some kind of animal to me. Something with horns . . .”

Thus begins Monty Python’s Life of Brian, which should restore our confidence in the belief that not all of the earth’s unnatural resources have been depleted. Just when you thought that the uproarious English comedy troupe had taken bad taste as far as it could go in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, along comes Monty Python’s Life of Brian to demonstrate that it’s possible to go even farther in delirious offensiveness. Bad taste of this order is rare but not yet dead.

The conniving mother of the Messiah in ‘The Life of Brian’

Monty Python’s Life of Brian succeeds in sending up not only movies like The Greatest Story Ever Told and King of Kings, but also a lot of the false piety attached to the source material. It is the foulest-spoken bibical epic ever made, as well as the best-humored — a nonstop orgy of assaults, not on anyone’s virtue, but on the funny bone. The film is like a Hovercraft fueled by comic energy. When it comes to a dry patch, it flies blithely over with no reduction in speed.

Life of Brian is the not-so-reverent account of the life, times and apotheosis of one Brian of Nazareth (Graham Chapman), a none-too-bright, would-be Judean freedom fighter who deeply annoys Pontius Pilate and whom people keep trying to turn into a messiah. According to the Monty Python gospel, the principal business in the Holy Land is the organization of inept liberation movements, while the people are made dozy by dozens of aspiring messiahs, including one fellow who warns of the coming of the awful day when “things will go astray . . . a father’s hammer, various household items . . .”

The movie was directed by Terry Jones (co-director of The Holy Grail) and written by Mr. Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle, Mr. Jones and Michael Palin, all of whom turn up in the film in dozens of major and minor roles, not all of which can be distinguished by anyone except the mother of the individual actor.

The Sermon on the Mount in ‘The Life of Brian’

There is no way to criticize these hijinks adequately, except to inventory some treasured moments. One that I recall most fondly is a sermon on a mountain so distant that the listeners can’t quite catch the words. “Blessed are the Greeks?” says one man. “How very curious.” “What did he say?” asks another fellow, “‘Blessed are the cheesemakers?'” A third man explains: “He’s not talking literally. What he means to say is blessed are manufacturers in general . . .” (Vincent Canby, New York Times)

‘Monty Python’s Life of Brian follows a young man whose life parallels Jesus. As an infant he is visited by the three wise men when they accidentally stop at the wrong manger. Thirty-three years later, poor Brian is a mess. He attends the Sermon of the Mount but just can’t make out the words due to the bickering of people around him. (“Blessed are the cheese makers?”)

When Brian joins a guerilla movement to fight against the Romans, events lead to him being mistaken for the Son of God. Of course, the Romans will have none of this, and Brian is crucified. Things don’t look so bad though, as Brian and other crucified victims sing the rousing ballad, “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life.”

‘Always Look on the Bright Side of Life’ is sung at an inopportune moment in ‘The Life of Brian’

The film viscously pokes fun at different approaches to religion. The Judean People’s Front is an underground organization that never can quite get out of the planning stages and fights endlessly with the People’s Front of Judea. The followers of Brian take their messiah’s discarded gourd and sandal, and hold them up as sacred relics. Sick people show up on Brian’s door demanding healing. When Brian shouts out to a mob of followers that they are all individuals, they shout back in unison, “Yes, we’re all individuals.” When one person says softly, “I’m not,” he is shushed into silence.

(See a video clip of Life of Brian: we’re all individuals.)

Life of Brian was unfairly criticized for being an anti-Jesus film. However, the Pythons never attack Jesus or his teachings. Their targets are those religious zealots who take Jesus’ simple messages of peace and love and use them as crutches or as cries for war and persecution. The Passion of the Christ may have been successful in capturing the pain and suffering that Jesus experienced when he died for the sins of humanity. Who knows? But Life of Brian successfully captures the pain and suffering humanity goes through every day at the hands of these lunatics and blind followers of religion.’ (Uri Lessing)

Save

Search Box

![]()

Study Resource for Bible movies: Passion of the Christ, Ten Commandments, Ben Hur, Greatest Story Ever Told, Gospel According to St Matthew, The Robe, Life of Brian, Jesus of Montreal, The Bible

Bible movie links

The Ten Commandments

Passion of the Christ

Gospel according to Matthew

Jesus of Montreal

The Bible

Ben Hur

The Robe

Greatest story ever told

Life of Brian

____________

Movie links

Hollywood versus Europe

Salome’s dance and the beheading of John the Baptist in ‘Salome‘

The same dance, the same scenes, but utterly different in Pasolini’s ‘Gospel according to Matther’

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher