Altars: why offer sacrifice?

Ceramic incense altar,

10th century BC

- Imagine you are standing in front of an ancient altar. You are making an offering to some ‘being’ – you don’t quite know what that being is, but you offer it anyway. Why? Because this mysterious power might be pleased with you – and return the favor by giving you what you ask for.

- How do you make that offering? You place the gift on the altar and then you destroy it (so that it could never belong to anyone else). If it was a sacrificial ritual, the blood of the animal/bird was sprinkled on the altar.

Why did people do this?

Humans have always wanted reassurance – and people in the ancient world were no different. They wanted to feel safe, with some control over what happened in their lives.

How do we know? At the beginning of the Trojan war in the Iliad, Achilles makes a speech that gives an insight into why ancient people offered sacrifice:

“Come, let us ask some seer, or priest, or maybe a reader of dreams – who may tell us why Phoebus Apollo is so angry: whether he sees fault in us for some vow or sacrifice neglected.

Perhaps in return for the smoke of lambs and sacrificial goats, he will save us from the pestilence.”

The Altar as a banquet table

How did it work? The altar was a table on which banquets were prepared for the god.

The altar was a sort of platform or table on which gifts to the deity were placed.

A ‘high place’ altar at Petra

Think of the altar as a sort of hearth – a central point in a house where a fire was kept alight at all times. The hearth was the focus of the house and all who lived in it. Fire kept people safe, it kept them warm, and it cooked their food.

The altar was like this hearth, a focus for the community and a point of safety.

The Temple was the house of God and, as such, it needed a hearth. The altar fulfilled this role.

A small incense altar

This aspect is not stated explicitly but it is apparent from the way in which a fire was always kept burning upon the altar (Leviticus 6:12-13; ll Maccabees 1:18-36), just as a lamp had to be kept permanently alight in the Temple (Exodus 27:20-21; Leviticus 24:2—4).

Who offered a sacrifice?

In the time of Abraham and Moses times, sacrifices could be offered by anyone.

Things changed when the Israelites settled in Canaan. Ministry at the altar became the office of the priests.

As sacrificial ritual developed, so the altar became more important.

Massive stone hewn into an altar

What were Canaanite altars like?

An altar in ancient Canaan might be simply a flat rock, or a rock hewn into a specific shape.

- In the 13th century BC Canaanite temple at Hazor, an altar was found made of an enormous rectangular block, with a basin hollowed out on one of its surfaces.

- In many Canaanite sanctuaries dating from 3000 BC to the 14th-13th centuries BC, altars built of large stones and earthen mortar were found standing against the back wall.

- The high place or bamah had altars made of great stones such as the one at Megiddo (see pictures below).

- At Gezer, the altar had hollows in its surface leading down into a cave where the bones of sacrificial animals were found.

Altar at the ancient city of Megiddo

The circular altar at Megiddo was in the far right quarter of the city, in a separate temple complex

Early Israelite altars

The earliest altars mentioned in the Bible, from Patriarchal days to the early period of the monarchy, were built of stone. Exodus (20:24-26) lays it down that altars should be built

- either of plain clay bricks or

- of stones which have not been trimmed.

No steps led up to the altar so that it could not be exposed to profanity. Profanity, you ask? Yes. Officiating priests wore loincloths, and in stepping up onto the altar they might inadvertently have exposed their genitals. Hebrew altars could contain nothing profane, even if the profanity was unintentional.

The Book of Exodus also gives descriptions of

- the altar of holocausts (27:1-8; 38:1-7) and

- the altar of incense (30:1-5) used in the desert.

The Book describes them as elaborate structures of acacia-wood plated with bronze and standing two or three cubits high (4 or 5 feet). Many scholars think these specifications refer to David’s version of the Tabernacle, rather than the desert Tabernacle carried by the tribes fleeing from Pharaoh in Egypt.

What was the Horned Altar?

The re-assembled ‘horned altar’

Archaeologists excavating at Beersheba found several large, carefully shaped stones incorporated into the town walls. These stones dated back to the late eighth century BC.

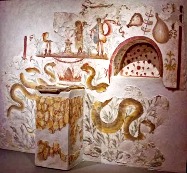

When the stones were reassembled, they formed a cubical altar with four tapered projections or ‘horns’ – see the reconstruction above. One of the stone blocks had a snake carved onto it.

The top stones were blackened, suggesting that sacrifices had been burnt there.

This altar may have been dismantled at the time of King Hezekiah’s religious reforms in the 8th century BC. For more on the excavations, see Beersheba

The design of an ancient altar

There have been various theories about why the altar had projecting ‘horns’. The most practical reason would be that the high corner stones provided leverage for the ropes necessary to hold down a struggling animal as it was being sacrificed. They may also have referred to the four points of the compass

On the other hand, two areas would have been needed, one to slaughter the animal, the other to burn it. The same areas could not sensibly be used for both tasks, since the volume of blood from an animal with its throat cut would make any surface so wet that a fire would not burn.

There must have been several stages in a sacrifice:

- the selection and preparation of the animal

- prayers of supplication or thanksgiving to the deity

- the killing of the animal

- the burning of pieces of the animal

- distribution of meat after the ceremony

Each of these actions had to be catered for in the design of an ancient altar.

Excavation of the ancient temple at Lachish. Notice the forecourt, the steps leading up to the altar, and the position of the altar itself.

The altar in Solomon’s Temple

The Rock of the Dome, on which Solomon’s Temple and its Altar are said to have stood.

The altars of Solomon’s Temple apparently included

- the bronze altar of holocausts which stood in front of the Temple (ll Kings 16:14) and

- the altar of incense in the “hekhal“’ in front of the Holy of Holies (l Kings 6:20-21).

The original altar of holocausts which stood 5 cubits high and was 5 cubits square, with steps leading up to it, was replaced by King Ahaz who installed a new model (ll Kings 16:10-16) which remained in use until the Exile.

The Temple altar must have been similar to other altars unearthed elsewhere, notably at Arad.

At Megiddo a typical lime-stone incense altar was found, shaped like a square pillar (as specified in Exodus 30:1-5), with four horns on the top corners. The blood of sacrificial animals was rubbed on the horns to consecrate it or in rites of expiation. In addition, a fugitive claiming asylum would grasp the horns of the altar (1 Kings 2:28).

In the Second Temple

The altars of holocausts and of incense in the Second Temple are described in ll Chronicles 4:1 and 29:16ff, since the Chronicler may have based his account of Solomon’s Temple on the fittings of the post-Exilic Temple with which he was familiar.

More reliable descriptions are found in non-biblical sources of the Hellenistic period. Josephus gives one account, and another is included in the Letter of Aristeas.

These describe the altar of holocausts as

- a square, 20 cubits wide and 10 cubits high,

- built of untrimmed stones according to the prescription of Exodus 20:25, and also in line with the Chronicler’s description. There was also

- an altar of incense (see an example towards the top of this page)

The altars were profaned in 164BC when Antiochus Epiphanes plundered the Temple, and they were rebuilt when the Temple was recaptured and purified by the victorious Maccabaeans (1 Maccabees 1:21; 1:59; 4:47).

Altar excavated at the ancient city of Arad

The desire for communication and reassurence seems to have been common all over the ancient world. At the beginning of the Trojan war in the Iliad, Achilles makes a speech that gives an insight into why ancient people offered sacrifice:

Come, let us ask some seer, or priest, or maybe a reader of dreams – who may tell us why Phoebus Apollo is so angry: whether he sees fault in us for some vow or sacrifice neglected. Perhaps in return for the smoke of lambs and sacrificial goats, he will save us from the pestilence.

The Altar as a banquet table

How did it work? The altar provided a table upon which banquets were prepared for the god in the form of sacrifices.

This altar was a sort of platform or table on which gifts to the deity were placed, along with petitions, thanksgivings, etc.

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher