Why did people make sacrifices?

When people in the ancient world offered a gift, a sacrifice to Yahweh or to the gods, they took the best living animal they owned and offered it as a gift.  They killed the offering, making it impossible for the gift ever to be taken back or reclaimed.

They killed the offering, making it impossible for the gift ever to be taken back or reclaimed.

It was the best they had. They gave it to God.

But hardly anyone gives something away without hoping for a reward. It was like this in the ancient world, just as it is now.

What did they hope to gain by making a sacrifice? Security, survival, health for themselves and their family, safety, prosperity: the things that all people, everywhere, have always wished for.

What gift should they offer to God?

The Israelites believed that everything belonging to a person acquired something of that person’s personality. Therefore, in making a gift, a person gave something personal, something they owned or had paid a substantial amount for.

They used the altar as a linking point between God and themselves. The gift being offered was placed and burnt on the altar, while the climax to the sacrificial ritual came when the blood – blood being the life force of the animal – was sprinkled over the altar.

Who offered the sacrifice?

In the time of the Patriarchs and Matriarchs, sacrifices might be offered by anyone. But when the Israelites settled in Canaan after their migration from Egypt, ministry at an altar in a recognized sanctuary became the prerogative of specially appointed priests.

What happened at a sacrifice?

The ceremony was carefully ordered. There was a strict procedure that had to be followed. Everything had to be exactly right, or else the sacrifice was voided.

Sacrificial altar excavated at Megiddo

There were six stages in the ritual:

- The worshipper brought his animal/bird to the place of sacrifice, i.e. to the ‘door’ of the Tent of Meeting, or into the court of the sanctuary, north of the altar.

- The worshipper lay his hands on the head of the animal (Leviticus 3 :2, 8 etc.) and said, loud and clear, what he hoped to gain.

- The animal was slaughtered by the worshipper in the case of an individual offering, or by the priest in the case of community offerings (Leviticus 16:11; II Chronicles 29:24).

- The blood of the sacrifice was collected in a bowl on the northeastern or southwestern corner of the altar, and then sprinkled by the priest on all four sides of the altar(Leviticus 1:5; 7:2). When the victim was a turtledove or pigeon (Leviticus 1:15) with little blood, it was drained on to the wall of the altar.

- The burning: Apart from the blood which belonged wholly to God, the ‘fat covering the entrails and all the fat that is on the entrails and the two kidneys with the fat that is on them’ (Leviticus 3:3-4) had to be burned on the altar.

Roman boy leading a sacrificial goat. Ostia

In peace, sin or guilt offerings, these parts alone were burnt, but in the case of an ‘olah‘ or whole burnt offering in atonement for the sins of the community, the whole carcass was burnt, only the liver being saved and given to the priests (Leviticus 7:4).

- The feast: The parts of an offering which were not burnt were served at a solemn feast. Peace-offerings were served to both worshipper and priests (Leviticus 7:32); offerings might be served to the worshipper, his family and the priests, or, in some cases, to the priests alone. The priests’ portions of peace offerings (Leviticus 10:14; 22:10 ff), first-fruits and tithes were considered holy, but the priests and their families could eat them in any pure place in Jerusalem. Sacrifices of reparation and sin offerings (Leviticus 6:26; 7:6) and the meal offering were considered most holy and could only be eaten by the priests within the precincts of the Tent of Meeting, or in the Temple court.

How did the Greeks sacrifice to the gods?

The religions of the Graeco-Roman world included observance of the thusia. This was a rite in which a portion of an offering was solemnly and ceremoniously offered to the deity and burnt upon the altar, after which the remainder was eaten by priests or worshippers in a common meal.

The thusia was a fixed element in the Mycenean culture and was continued by the Greeks.

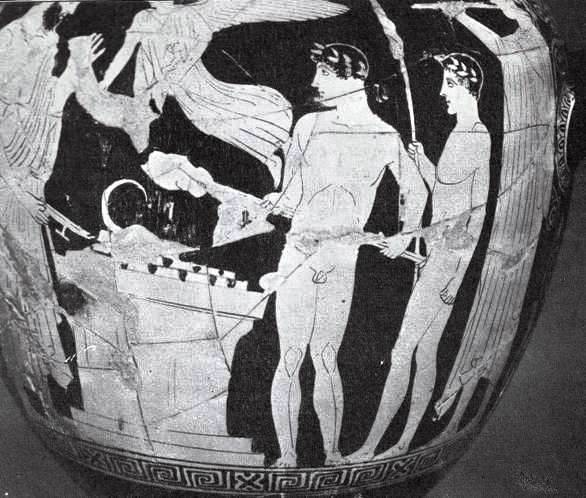

Two youths with five-pronged forks make a burnt offering to the gods. The priest stands at left. Greek vase

Worshippers at a thusia did not just stand and watch. They took part in the ceremony.

The rite began with

- lustration (ceremonial washing) and

- the scattering of barley grains,

- followed by prayers in the form of vows and thanksgiving, then

- the burning of the victim and

- ending with a formal procession.

The central act was the solemn burning on the altar fire of pieces of the thigh of the animal wrapped in fat and covered with other pieces of meat, as in this vase painting (above) which shows the attendants handling the meat with five-pronged forks (the priest is standing on the left). Organs below the diaphragm were also eaten or at least tasted.

After the priests had taken the portions of the animal belonging to the god, the roasted victim was eaten in a banquet with wine, oil and honey, music and dancing. The thusia was used increasingly among the ancient Greeks to express thanks to the gods.

Over the centuries,

- magnificent temples took the place of open-air altars, and

- spontaneous acts of devotion to the gods were replaced by formal worship adopted by the different city-states and kingdoms of the Graeco-Roman world.

The Greeks also practiced special rites against evil demons in which sacrificial victims were burned at night and in complete silence, but these rites were carefully distinguished from the thusia, performed in daytime as an act of worship of the gods of Olympus.

How did the Romans sacrifice to the gods?

Rural scene of sacrifice on a Roman terracotta plaque. Notice the pipes being played (left) by Faunus, the Roman equivalent of the Greek god Pan

All Roman sacrificial rites were intended to propitiate friendly and avert hostile powers.

The rites were conducted by the priests with the utmost precision according to a ceremonial which preserved their mystical character.

The main features of the rites were

- the ceremonial preparation and immolation of the animal being sacrificed,

- a careful examination of the vital organs to make sure they were in perfect condition then

- the burning of the victim on the altar.

The whole ritual was carried out in complete silence, the only sound being the cries of the dying animal and music being played on pipes to drown any sound. Once the animal had been burnt, it lost its ritual sanctity and became the property of the priests.

The Romans never widely adopted the feasting that went on at Greek sacrifices.

Sacrificial ceremony on a Roman bas-relief

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher