Sarah’s story

- Sarah was matriarch of the tribes of Israel, their founding mother.

- Sarah’s life was blighted by the lack of a son. She was barren. In desperation she offered her slave Hagar to her husband Abraham – Hagar could bear him a son.

- The plan back-fired: Hagar bore a son Ishmael, and her status in the tribe rose. But Sarah became even more despised.

- God came to her rescue. She had a son, Isaac, whom she loved with the protective ferocity of a lioness.

- Sarah had Hagar and her son Ishmael expelled into the desert, where without God’s help they would have died of thirst.

1 Sarah and the Pharaoh of Egypt

The opening verses of the story throw us in at the deep end.

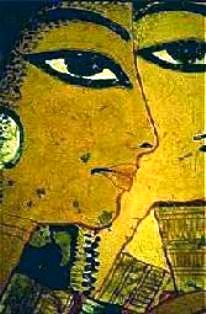

Sarah would have seen, and probably copied, the elaborate make-up worn by Egyptian women

Famine drives Sarah, her husband Abraham and their flocks southwards into Egypt.

In this strange land they are small fish in a big pond, uncertain of the treatment they will receive from the Egyptians – especially as Sarah is strikingly beautiful and likely to attract men’s attention.

So Abraham decides on a strategy. He will pass her off as his sister, not his wife. This way, men will be more likely to treat the group well. If they see Abraham as her husband, they may try to kill him to get Sarah.

Sarah agrees. Is she coerced into living this lie? Or is she the originator of the plan?

It is impossible to tell, since we don’t know what she feels about the matter.

Despite the later veneration of Sarah and Abraham, the Book of Genesis describes two people who are far from being saints. Later readers of the Bible gloss over the uncomfortable truths in this story.

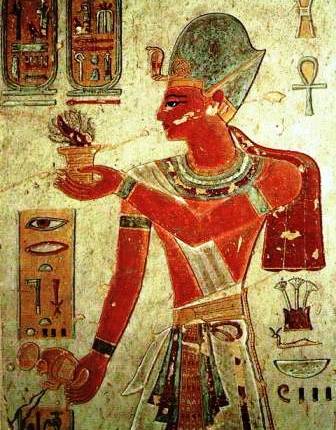

Wall painting of an Egyptian pharaoh

What Abraham feared, happens. Reports of her beauty reach Pharaoh. Accustomed to the best, he has his soldiers take Sarah from her family, and pleased with her, he places her in his harem. Presumably he has sexual intercourse with her.

The reader is puzzled. Aren’t Abraham and Sarah supposed to be paragons of moral behaviour? Well, no. The hero of this story is God, not humans, and time and again he rescues people from themselves.

God has a long-range plan, and He is not going to let humans mess it up.

So Pharaoh and his country become afflicted with plagues, and when he finds out that Sarah is Abraham’s wife, he views his misfortune as punishment from the gods for his inadvertent sin of adultery.

He hastily restores Sarah to Abraham, and pays compensation – even though it is clearly Abraham who is at fault.

Pharaoh’s generosity contrasts sharply with Abraham’s venal behaviour. Read Genesis 11:29-12:1-20

2 Sarah, Hagar and Ishmael

Sarah comes much more strongly into focus in the second part of the story.

After many years in a loving marriage with Abraham, she is still childless – a terrible curse for any Jewish woman of the period, but especially for the wife of a tribal leader.

Sarah leading Hagar to Abraham, Matthias Stomer, 1637

Eventually she has an idea. Speaking with great courtesy and formality to her husband, Sarah gives him her female slave, in the hope the girl with conceive a child to him.

It sounds strange to us, but this was an ancient legal form of surrogate motherhood practised at that time – see for example Rachel’s story in Genesis 30.

A related situation is covered by the Laws of Hammurabi, in items 146 and 147, which sound pretty harsh by modern standards:

146. If a man has married a votary (a priestess who left her duties to marry; she was not supposed to have children) and she has given a maid to her husband, and the maid has borne children, and if afterward that maid has placed herself on an equality with her mistress because she has borne children, her mistress shall not sell her, she shall place a slave-mark upon her, and reckon her with the slave-girls.

147. If she has not borne children, her mistress shall sell her.

Statuette of an ancient Egyptian female worker

Children born in this way were counted as the offspring not only of the husband who fathered them, but of the wife who owned the slave.

What about the slave girl?

The slave in question was usually happy to comply, since her status if she bore a child was considerably raised, and her life became easier. She was also allowed to look after the child, even though legally it belonged to the wife. (See Slaves for more information.)

In Sarah’s case, the plan is initially successful. The slave Hagar becomes pregnant, which is what Sarah thought she wanted.

You would think she’d be happy, but no. Things get worse. Neither woman can accept the change in Hagar‘s status:

- Hagar is rude and disdainful to her former mistress;

- Sarah resents what she sees as Hagar’s new airs and graces.

- Dominance is the issue.

Her disappointment comes spilling out in bitter words:

‘Sarai said to Abram “May the violence done to me be on you! I gave my slave-girl to your embrace, and when she saw that she had conceived, I became contemptible in her eyes. May the Lord judge between you and me!”(16:5)

Abraham points out that the girl belongs to Sarah, not him. Sarah, in other words, has legal jurisdiction over her – as she has to a lesser extent over the free-born women of the tribe.

Middle Eastern woman alone in the barren desert

The problem between the two women escalates into a real conflict, and eventually reaches the point where Hagar runs away, out into the desert – even though running away, if you are a slave, is a serious crime. Despite her pregnancy, Hagar is still a servant in the household – her words, and those of the angel, make this clear. (Genesis 16:8)

Hagar heads for Egypt, and home.

But God has pity on the unfortunate girl. God sends a messenger to save her, and she returns to Sarah, gritting her teeth and accepting harsh treatment from her mistress. (See Hagar for a fuller version of her story.)

Hagar’s baby is born. It is a boy. There is great celebration. Sarah, it seems, has achieved her goal.

But things get gradually worse. Sarah’s status within the tribe is greatly diminished, and as mother to the tribal heir, Hagar flaunts her newfound power. Sarah struggles against the humiliation and pain she endures, and lets Abraham know about it in no uncertain terms.

Her complaint is in vain. Nothing changes. Then God steps in again.

3 The Promise

God comes to Abraham and tells him that Sarah, despite her advanced age, will have a son.

Abraham is perplexed, to say the least, since both of them are so old. But nothing is impossible to God.

Sarah is not present at this encounter with God, and Abraham does not seem to have told her about it.

But the Bible as we have it was a book shaped for men’s study, not women’s, and so it deals with men’s experience. Women had their own sacred stories which probably emphasised the part played by women, but they were oral stories, never written down. Over the centuries they were mostly lost.

You can see this if you compare the lengths of the Songs of Moses (18 verses) and Miriam (1 verse) in Exodus 15. When the stories were first told, both songs were probably the same length.

4 The Three Visitors

Tents of a nomadic tribe

Read Genesis 18

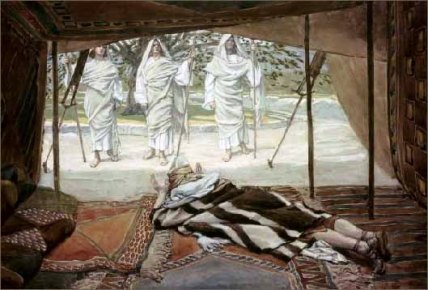

Later, God appears to Abraham again, but this time in disguise.

Abraham is sitting in the open front section of the tent. Sarah is in the back part, a private section for women and children separated from the front section by a heavy woven curtain.

Three men approach the tent – or are they angels??? Or is it God?

The English translation is unclear about who it is that approaches, but in Hebrew the meaning is plain:

what is actually there in front of Abraham is God, but what Abraham sees is three men.

Interior of a tent with Middle Eastern tribal men

Abraham greets the men with the ritual hospitality of the East. He runs forward, bows, offers and gives food and drink.

Meanwhile Sarah stays hidden behind the heavy curtain, as is proper (and safe) for a woman in the presence of strange men.

When they have finished eating, they ask about Sarah.

Abraham and the three angels, James Tissot

Where is she? She is to have a son, they say.

Listening from behind the curtain, Sarah hears this, and laughs. It is after all an absurd thing at her age.

The English version of the Bible describes her as ‘old’, but the original Hebrew word is more like ‘worn out’, as if she was an old rag ready to be thrown away. Her laughter suggests that she and Abraham have not had sexual intercourse for a long time.

The angels/men admonish her, even though Abraham also laughed in an earlier scene and was not reprimanded (Genesis 17:17).

Is anything impossible for God? the angels ask.

Frightened, off balance, Sarah denies laughing. Has she recognised the real identity of these strangers? Is this why she is suddenly afraid? But they insist: ‘Oh yes, you did laugh.‘

5 God warns Abimelek

Read Genesis 20

Just as you think things are straightening out for Sarah and Abraham, they blot their copy-book yet again. There is a repetition of the grubby incident in Egypt, where Abraham tricked Pharaoh.

Topographic map with the ancient city of Gerar

Passing through Gerar, a town in the south of Canaan, Abraham again tells people that Sarah is his sister, not his wife. The same old lie. This time it is a king, Abimelek, who is taken in and who sends for Sarah.

Abraham’s lie almost beggars belief. God has promised him a son by Sarah, and yet he allows another man the chance to have sex with his wife.

Does he doubt his own ability to have sexual intercourse with Sarah, and to father a child?

Or is he intent only in saving his skin when he is in danger?

The story-teller tries to mitigate Abraham’s lie by saying that it is, after all, only a half lie. Sarah is Abraham’s half sister as well as his wife, which is true. Marriage of a man and woman with the same father but different mothers was a fairly common practice then, though later forbidden.

God has promised a son to Sarah and Abraham. Yet Abraham throws the whole future into doubt by allowing Sarah to enter the harem of Abimelek. Only God’s intervention prevents Abimelek from having sex with Sarah, and jeopardizing the promise of an heir for her and Abraham.

The reader might wonder why is this shameful story is included in the Bible. What is going on? What is the purpose?

The answer?

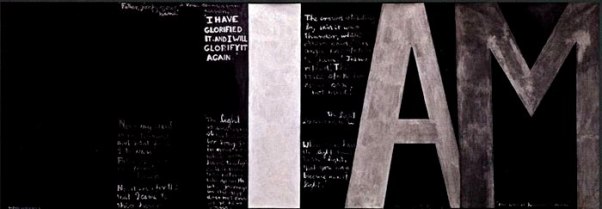

Despite everything that human beings do, despite their stupidity, greed and cowardice, the inexorable plan of God unfolds as God meant it to. Even sinners can be instruments of God. This is the central message of the story of Sarah and Abraham. Do what we will, humans cannot thwart the Will of God.

Colin McCahon’s majestic painting ‘I Am’

6 Isaac born, Hagar & Ishmael expelled

The climax of Sarah’s story, the event she has awaited all her life, comes. Her son Isaac is born.

She is overjoyed, laughing with pure happiness. She even names her child ‘Isaac’, which means laughter. Like some primeval goddess, Sarah has brought Laughter into the world.

The baby boy is everything she hoped for, and more, and she dotes on him.

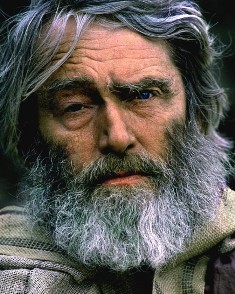

Sarah and Abraham with the newly born Isaac,

still from the movie ‘The Bible’

Lavished with care and love, the little boy thrives. Eventually when he is about three years old it is time for him to be weaned from breast milk. There is a great party to celebrate this event: babies in the ancient world had a high mortality rate, and staying alive past infancy warranted celebration.

All seems well – until something sinister happens and the happiness evaporates.

All seems well – until something sinister happens and the happiness evaporates.

We are not sure what exactly it was that caused this jarring note. Some translations say that Sarah saw Ishmael ‘playing’ with Isaac. Others describe him as ‘mocking’ the little boy. The original Hebrew word is s-h-q. It can mean ‘to play’, ‘to laugh’ or ‘to sport’, and in fact has a wide range of meanings. Later, in the Greek translation, the words ‘with her son Isaac’ were added.

There have been many suggestions about what the word ‘play’ implied. The most likely is that Sarah saw Ishmael play-acting the moment when he would take over as leader of the tribe, and dealing with his rival Isaac. It was quite common in Canaanite and Egyptian society for new leaders to murder their half-brothers when they came to power.

Barren desert

Whatever it was, it terrifies Sarah. She sees Ishmael and his mother as a threat to her own son. She senses that there is trouble ahead, bad trouble, and asks, demands, that Abraham send Hagar and Ishmael away, immediately. She is like a lioness protecting her cub:

‘Cast out this slave woman with her son; for the son of this slave woman shall not inherit along with my son Isaac’ (note that Sarah and Abraham never once use Hagar’s name).

Abraham does not want to comply – Ishmael is his son – but Sarah prevails. It seems she still has legal dominion over Hagar, and she uses her power.

Next morning Abraham gives Hagar and the boy Ishmael some water and bread, and sends them out into the unforgiving desert, abandoning them to their fate. Technically they are free: Hagar is now an emancipated slave. In reality they are in a very precarious position, and only God’s intervention saves them.

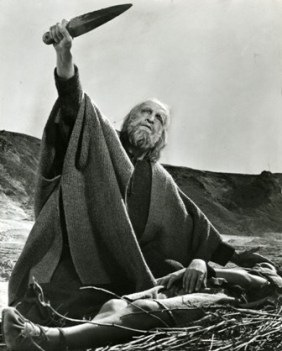

Abraham prepares to sacrifice Sarah’s only child, her son Isaac

This direct intervention (through an angel) has an unspoken message: that the treatment of Hagar is illegal. God has spoken out against it. In fact, Hammurabi’s Law would have required Abraham to give Ishmael a specified portion of inheritance, since Abraham has adopted the lad.

But Sarah has won. She has a son who will become the next tribal leader. Her remorseless speech against Hagar are the last words we hear from her.

7 Sarah’s story ends

Read Genesis 22, 23:1-2

Before she dies, there is one more event that Sarah has to deal with: Abraham’s aborted sacrifice of his (and Sarah’s) son Isaac (Genesis 22).

Sarah is not mentioned in this incident, but she must surely have known about it – either before it happened, or after.

Her side of the story has disappeared, but can anyone doubt what her reaction was, or how horrific this event must have been for her?

She died soon after this at Hebron, which became a sacred city of the Israelites.

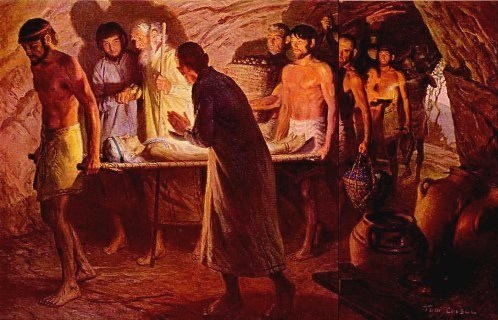

The Burial of Sarah, showing bier and interior of tomb

Main themes in Sarah’s story

God has a long term plan for humanity that involves Sarah and Abraham: they are to be the forebears of a great nation.

God has a long term plan for humanity that involves Sarah and Abraham: they are to be the forebears of a great nation. - This is ironic, since they are rich in material goods but have no children, and moreover seem determined to put obstacles in the way of God’s plan.

- Undeterred by human foolishness and sin, God continues to protect and guide them, and eventually a son is born to Sarah and Abraham, a boy called Isaac. His name means ‘laughter’. But who is laughing? Sarah? Or God?

Names in the Bible story

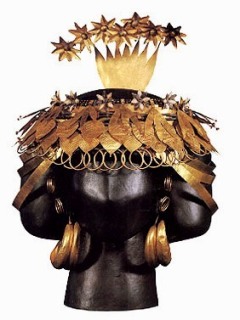

Golden headdress of Queen Puabi, excavated at the ancient city of Ur

Sarai means ‘lady’, a woman with high social status

Sarah means much the same, but with more emphasis – like ‘Duchess’ (high social status) and ‘Princess’ (very high social status). It may have been short for Ummu-sarra, which meant ‘the great mother is queen’

Abram means ‘honoured or exalted father’

Abraham means ‘father or ancestor of many people’

Isaac means ‘may God smile/laugh’, perhaps a reference to his mother Sarah’s laughter when she heard she was to become pregnant in her old age

Hagar means ‘stranger’. No-one except the angel uses her name when they speak to her

Ishmael means ‘God hears’. Twice when his mother Hagar is abandoned by others, God hears her or her son and helps them.

Note: Sarah and Abraham are at first called Sarai and Abram; later God makes a promise to them, a covenant, and their names change to Sarah and Abraham. To minimize confusion, I use ‘Sarah’ and ‘Abraham’ throughout.

Sarah’s story: the Bible references

1 Sarah and the Pharaoh of Egypt, Genesis 11:29 – 12:1-20

2 Sarah, Hagar and Ishmael, Genesis 16

3 The Promise, Genesis 17

4 The Three Visitors, Genesis 18

5 God Warns Abimelek Off Sarah, Genesis 20

6 The Birth of Isaac, Hagar and Ishmael Sent Away, Genesis 21

7 The End of Sarah’s Story, Genesis 22, 23:1-2

Some suggested extra reading:

- Tikva Frymer-Kinsky: Reading the Women of the Bible, 2002, p225-237

- Dennis, Trevor, Sarah Laughed, 1994, p34-61

- Schneider, Tammi, Sarah Mother of Nations, 2004.

Sarah, Bible woman

Study guide for Sarah, Abraham and Hagar in the Book of Genesis

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher