The moral point that Jesus was making concerns the nature of sacrifice: the offering of a poor widow was worth more than that of rich people who put into the Temple treasury’s collection boxes large sums out of their overflowing wealth.  Although the poor widow offered a mere couple of coins (the Greek word signifies the lowest possible denomination, less than a penny, somewhat akin to the Indian pice), that, we are told, was ‘all that she had’.

Although the poor widow offered a mere couple of coins (the Greek word signifies the lowest possible denomination, less than a penny, somewhat akin to the Indian pice), that, we are told, was ‘all that she had’.

What does that phrase mean? It is improbable that Jesus intended to mean ‘all that she had on her’, for anyone might find themselves with only very small change and there would belittle praise for offering that to the treasury collection box if there was plenty more money at home.

Was Jesus exaggerating? He did sometimes use the common Jewish practice of hyperbole in order to drive home his point (e.g. that is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven).

Did he use it here? We cannot be certain. One must suppose that the widow had the coins with her because she had intended to buy something with them, probably some food; otherwise they would have been kept securely at home. On an impulse she gave to God all the money that she possessed, small as that was.

The Miracles of Jesus, Hugh Montefiore, SPCK, London, 2005, p.30

Jesus exemplifies the traditional Jewish awareness of and concern for widows.

- He uses the story of Elijah, fed by a Phoenician widow, to illustrate how a prophet may be rejected by his own people (Lk 4:25-27);

- he uses the image of a persistent widow to illustrate the need for perseverance in prayer (Lk 18:1—8);

- from his cross, he provides for the care of his own widowed mother (Jn 19:25-27);

- and he personally helps one widow and praises another.

One is the widow from Nain, whose only son Jesus restores to life. The other is a poor widow whose tiny financial contribution to the temple Jesus praises as surpassing the philanthropy of the rich—-a woman whose story is often called that of the “widow’s mite.”

One is the widow from Nain, whose only son Jesus restores to life. The other is a poor widow whose tiny financial contribution to the temple Jesus praises as surpassing the philanthropy of the rich—-a woman whose story is often called that of the “widow’s mite.”

….In ancient Israel, three kinds of people-the alien, the widow, and the orphan—were especially vulnerable. For that very reason, Yahweh was said to love them and to visit wrath upon all who oppressed them (Ex 22:20-23; Deut 10:18, 24:17, 27:19).

The plight of a widow was a special matter of concern, because the concept of “independent woman” simply did not exist. Strong widows like Tamar (daughter-in-law of Judah) and Ruth were the exception. By New Testament times, a widow might be protected by a financial settlement specified in a ketuba (a marriage contract), or she could sue her husband’s estate to recover part of her dowry. But as a rule, a woman depended upon a father, husband, or son.

A childless young widow might remarry or return to her father’s house; the future of an older widow was more precarious. A brother or close male relative of her husband might honour the Levirate customs of Israel by marrying her, but he could refuse to do so (Deut 25 :9-10; Ruth 4:6).

Thus an older widow who had no children could be left penniless and open to victimization by creditors, judges, or anyone with a modicum of power.

By Jesus’ time, lawyers and scribes could gain a share in her property by administering it for her. Since widows would be attracted toward those legal experts who were known to be religiously observant, Jesus reserves harsh castigation for any scribe who prayed ostentatiously while simultaneously “devouring the houses” of widows—cheating them (Mk 12:38-40 and Lk 20:45-47).

Their Stories, Our Stories, Rose Sallberg Kam, Continuum Publishing Co., New York, 1995, p,200-201.

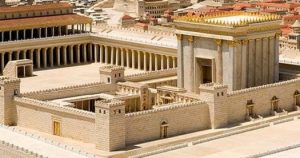

‘On a long day of controversies and teachings in the Temple, just before telling his disciples about the signs of the coming end of the World, Jesus watches a poor widow throw two coins into the Temple treasury.

Widows need not be poor, as this one was (and some wealthy widows might have been very influential members of early Christian communities), however, their status was often tentative, because their husbands, their major source of protection and identity, were dead.

While sons, other male relatives, or family wealth could provide some measure of security, widows were traditionally considered subjects of special moral concern because of their generally defenseless legal and financial position.

While sons, other male relatives, or family wealth could provide some measure of security, widows were traditionally considered subjects of special moral concern because of their generally defenseless legal and financial position.

In the scene immediately preceding this one, Jesus condemns the scribes for, among other things, consuming the homes of widows (12:40), which probably refers to the practice of appointing some supposedly well-reputed and pious man to oversee the affairs of a widow, only to have the individual use the estate for his own gain. The widow who comes to the treasury, then, is not only disadvantaged by poverty but also by her vulnerable status, which makes her almost invisible in the legal, religious, political, and social eyes of her society.

Jesus had been watching many rich people put in large sums of money, when he observed the widow throw in the tiny amount of a “penny.” However, to his disciples he asserts that the widow’s offering is greater than any of the others because she has given all that she has, ‘her whole living’.

Besides indicating that what matters to God is the nature of the act of giving itself rather than the gross amount given, Jesus’ saying also underlines the ultimate or total nature of the financial sacrifice made by the widow. For one whose only protection from complete destitution is the little money she possesses, to give all of it to the Temple is to consign herself to disaster,- yet this she does without fanfare or desire for glory, but out of faith.

Such indifference to conventional human desires for security, wealth, and status stand as a very appropriate introduction to Jesus’ teaching on the coming end of the world, for at that time faith in God and not faith in human wealth and status will establish ones membership in the saved elect of the coming kingdom.’

Women’s Bible Commentary, Newsom & Ringe Eds., John Knox Press, p.357