What’s on this page?

Books about warriors, warfare and weapons in the Bible.

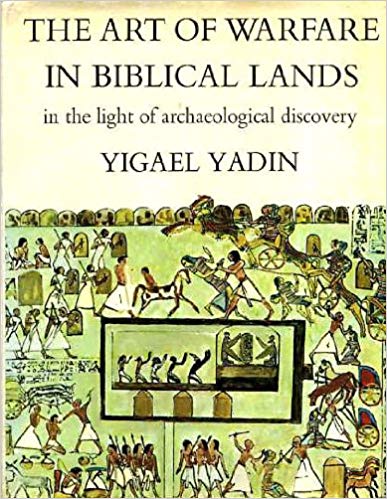

‘Human conflict finds expression in the first pages of the Bible. Hardly has man begun life on earth when, as the Biblical narrative records with unadorned simplicity, “Cain rose up against his brother Abel and killed him.”

The chain reaction to this event has continued right up to the 20th century. A study of human history cannot therefore be complete without a study of the military events of the past and of the means conceived by nations to secure their own military aims and thwart those of their enemies. Moreover, in ancient times, as today, men devoted much of their technical genius to perfecting weapons and devices for destruction and defense.

Weapons of war thus serve as an enlightening index of the standards of technical development reached by nations during different periods in history.

Since war always involves at least two sides, the development of the art of warfare of one nation can only be fully evaluated in the light of the art of warfare conducted by its enemy, in attack and defense. As an object of military study, a single land or nation is too limiting and conf1ning—and can be misleading. The smallest unit of such a study is a region or a group of peoples who battled each other at some period or another in their history. One must examine the reciprocal effects of such encounters, which enabled each side to gain knowledge of the weapons and fortifications of the other, to copy them and improve upon them.’

The Art of Warfare in Biblical Lands, Yigael Yadin, McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, 1963, p.1.

_______________________________

‘These principles are illustrated in cameo form at any boxing match, in which the contenders are even unarmed. The constant movement of the body has a single purpose: to put the boxer in the most advantageous position from which he can both attack and at the same time evade the blows of his opponent.

The predominant role of one fist is to attack — firepower; of the other, to parry – security.

To gain this advantageous position, the boxer has to know where his opponent is — or is likely to be at a given moment — and to seek out his weak spots. In this he is served by his senses — sight, sound, and touch.

His eyes, ears, and hands provide him with the intelligence which, in battle, is provided by reconnaissance units on patrol or at forward observation posts.

The action of his fists and other parts of his body is directed by his brain, through the medium of nerves and muscles.

Their counterpart in warfare is the military commander and his staff, as the brain; their nerves — the communications network; their muscles — trained and disciplined troops.’

The Art of Warfare in Biblical Lands, Yigael Yadin, McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, 1963, p.3.

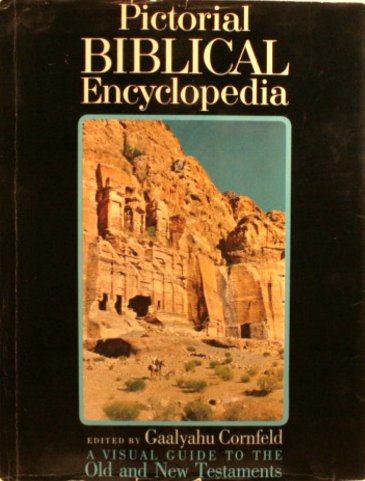

Surprise Attacks: An army which is weaker in numbers, weapons or skill will always try to gain an advantage by attacking unexpectedly.

At the time of the Conquest, Joshua’s band of Israelites was not a properly organized army and wherever possible it avoided making direct attacks on the fortified cities of Canaan. Instead, the Israelites sometimes tempted the defenders to leave their walls and to fight in the open.

More often, they relied on surprise. For instance, when the confederation of Canaanite city-kings joined together to attack Gibeon which had come to terms with the Israelites,  Joshua took his army on a 30 kilometre night march from their main camp at Gilgal near Jericho and caught the Canaanites by surprise. He used the same tactics to surprise another Canaanite alliance under the king of Hazor near the “waters of Merom” (Jos. I117).

Joshua took his army on a 30 kilometre night march from their main camp at Gilgal near Jericho and caught the Canaanites by surprise. He used the same tactics to surprise another Canaanite alliance under the king of Hazor near the “waters of Merom” (Jos. I117).

At a later period, night attacks were a favourite tactic of Gideon (Jud. 7:I7 ff). Tactics like these were especially effective in hilly country where the Canaanite chariots could not be used.

Such country was also very suitable for successful ambushes. A group of Israelites would pretend to flee before their foes, leading them to where the main army waited to fall upon them on all sides (Jos. 8:15—19; Jud. 20:32-36).

This was a favourite device when attacking a city. As the attackers seemed to flee, the defenders would be enticed after them and a waiting band could then make a dash for the gate.

Pictorial Biblical Encyclopaedia, Gaalyahu Cornfeld, Macmillan Co., New York, 1964, p.698

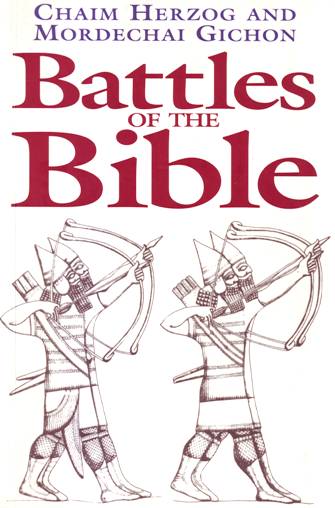

When the armies clashed on the following day, picked chariot troops attacked with the sole mission of hunting down Ahab and killing him. When one of these units attacked Jehoshaphat by mistake, it immediately broke contact when the king of Judah was properly identified.

Ahab had been in the forefront of the mélée from the start. By chance he had escaped the attention of the units of charioteers sent to trap him. But, while the battle was raging, a stray arrow struck between the joints of his armour and entered deep into his body. Seriously wounded, he was unable to carry on the assault personally.

At the same time, however, the Aramean opposition was so strong and resolute that Ahab was afraid of leaving the battlefield even for a short time to dress his wound, in case his action was misinterpreted and led to an Israelite retreat. ‘And the battle increased that day: howbeit the king of Israel stayed himself up in his chariot against the Syrians until the even: and about the time of the sun going down he died’ (2 Chr. 18:34).

By heroically bleeding to death and hiding his mortal wound from the eyes of his troops until evening, and only then collapsing in mortal exhaustion, Ahab had averted defeat.

Yet before the armies renewed their struggle on the following morning, the news of Ahab’s death had spread among his troops. In the absence of any other outstanding leader to use this news to create anger and a clamour for revenge, consternation was paramount and the dispirited Israelites and Judeans retreated, ‘every man to his own city and every man to his own country’.

Battles of the Bible, Chaim Herzog & Mordechai Gichon, Greenhill Books, London, 1978, p.166-7.

WARFARE, ARMIES, AND WEAPONS The fact that milhama ‘warfare’, appears over three hundred times in the Bible attests that warfare was a prominent feature of Israel’s history. When the North (Israel) and the South (Judah) were not fighting a common enemy, they were fighting each other.

Several factors account for biblical Israel’s frequent military encounters with neighboring peoples, among them Israel’s strategic location at the crossroads of the ancient world, with Mesopotamia to the northeast and Egypt to the southwest.

Israelite territory had a special appeal to imperial powers, since the primary trade routes between Egypt and Mesopotamia, connecting with the Mediterranean seaports, passed through Israel. For this reason, Assyria invested Israel and turned it into a province, but let Judah remain.

Judah was not very important to Assyria until about 700 B.C.E., and even then was not worth turning into a province.

Life in Biblical Israel, Philip J King & Lawrence E. Stager, Westminster John Knox Press, 2001, p.223.