Paintings of Judith in the Bible

Hidden meanings in paintings of Judith

- Watch for symbolic colors in the paintings: red means sexual passion; white is purity of behaviour or intent; gold is nobility;

black is the color of death.

black is the color of death. - The first paintings of Judith, produced in the Middle Ages, showed virtue overcoming vice.

- During the Renaissance a different theme emerged: Judith was an example of Man’s misfortunes at the hands of scheming Woman.

- The decapitation of Holofernes has sexual overtones: a man is robbed of his virility by a beautiful woman.

- In fact, Judith was a Jewish patriotic heroine and a symbol of the Jews’ struggle against their ancient, more powerful, overlords.

‘Judith with the Head of Holofernes’, Lucas Cranach, 1530

Judith’s right hand holds the sword, instrument of death. The fingers of her left hand are entwined in Holofernes’ hair, as she toys in an absent-minded way with the lifeless head.

If you are looking for subtlety, walk on by. Cranach the Elder is not your man.

But if you value a strong, no-nonsense message about God, faith and salvation, you may want to look more carefully at Cranach’s work.

Cranach was a close friend of Martin Luther (the famous portrait of Luther is by Cranach), and helped promote his ideas – he was a staunch supporter of the Protestant Reformation.

The story of Judith struck a chord with the Protestant reformers, since it described the courage of a small nation resisting a tyrant from outside who sought to impose his own beliefs about God on them.

The Protestant states cast themselves as Judith, and Catholicism and the Pope as Holofernes.

There was also an attempt at this time to balance the preponderance of male heroes in Christian tradition with biblical heroines who could be role models of particular virtues.

Cranach’s paintings are always beautiful (as God is) but evil lurks just beneath the surface.

See the Bible text for this story

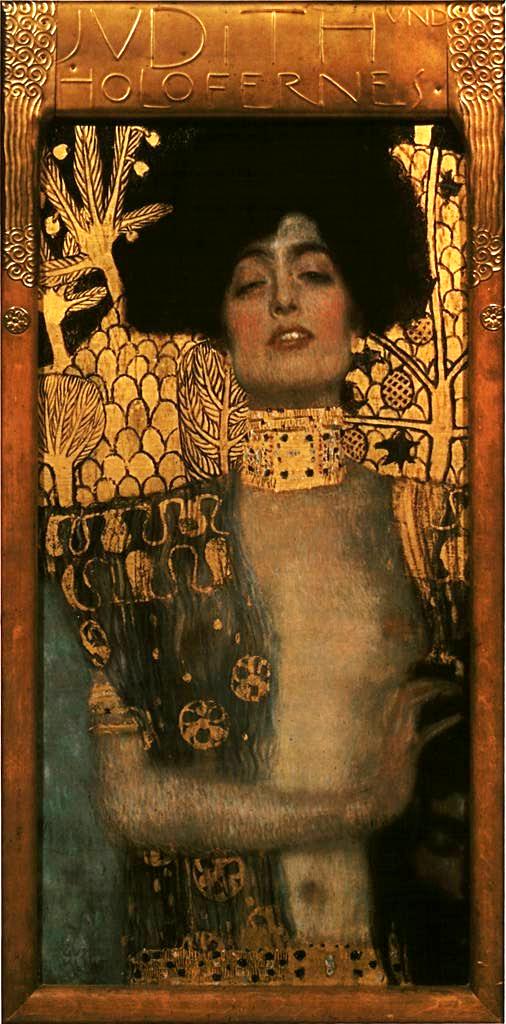

‘Judith and Holofernes’, Gustav Klimt, 1901-2

Judith is dressed in the rich clothing and lavish jewellery she wore when she went to meet Holofernes. She is a woman of gold.

Does the oversized golden choker at her neck suggest decapitation? Her clothing is disarrayed, but her look is triumphant as she holds the head of her enemy by her side.

There are similarities between this Art Nouveau painting and Byzantine icons: both make lavish use of gold leaf, both depict female heroines in elongated form.

The gold-leaf landscape behind her, with laden palm trees, is reminiscent of ancient Assyrian wall drawings of the Tree of Life.

And is that a Star of David above her left shoulder?

See the Bible text for this story

Beheading Holofernes

‘Judith Beheading Holofernes’, Caravaggio, 1599

Judith has steeled herself to cut into Holofernes’ neck, using his own sword.

The maid Abra stands ready to catch the severed head when it falls away.

Abra is one of the most over-looked figures in the Old Testament; she is with Judith every step of the way, and clearly gives her not only a servant’s support, but a large measure of courage as well.

Caravaggio has painted a magnificent Holofernes, muscled, strong, powerful. His horrified face is the attention-grabbing focus of this picture.

Judith, on the other hand, slices his neck with a look of mild distaste, as if she is carving the Sunday roast.

The colors, harmonious composition and shading of the painting are superb, as we would expect from Caravaggio.

But magnificent as the painting is, it does not convey the ghastly horror of the event.

See the Bible text for this story

‘Judith and her Maidservant’, Artemisia Gentileschi, 1613-14

Judith’s maid Abra has gathered up the head of Holofernes in a basket, and they are preparing to leave his tent when they hear something which makes them stop and listen.

The danger of their situation is implied by the position of the sword in Judith’s hand: a few more inches and it will cut into her own white throat.

Close-ups of the painting show that the brooch in her hair is a picture of a warrior, perhaps the biblical David who is the male equivalent of Judith.

See the Bible text for this story

‘Judith’, Gustav Klimt, 1909

Judith stands, her fingers clenched in the hair of Holofernes’ head. Her gorgeous robe has fallen away from her body and her hair is disarranged, but she seems calm, oblivious of her surroundings, almost in shock.

This painting has often been labeled ‘Salome’, because it depicts a half-naked woman carrying a man’s severed head. In fact, the woman is Judith, not Salome.

Though it is an archetypal Art Nouveau painting, there are many similarities with Old Master images of Judith: a remorseless, half-clothed woman, disguised tension in the rigid hands, the sumptuous dress.

See the Bible text for this story

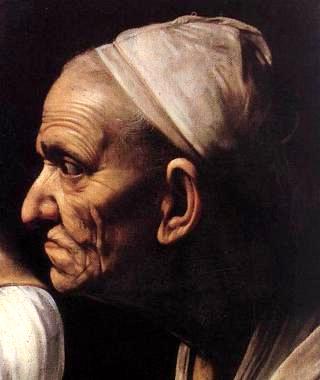

‘Judith with the Head of Holofernes’, Carlo Saraceni, 1615-20

The maid’s anxious face looks up for reassurance to Judith, who despite the horror of the situation appears calm, almost serene. She holds the head of Holofernes in her left hand, ready to drop it in the bag held by her maid.

The darkness of the painting suggests the secretive nature of what they are doing, the need for stealth.

In reality it is unlikely that Judith was as calm as she appears in this picture, but there is an unexpected touch of realism in the way the maid holds the bag. She grips one point between her teeth and makes an opening by holding two other points with her hands – just the way you would to make an opening for a large round object, be it a cabbage or a human head.

There are only subtle indications of the violent murder that has just occurred: the reddened fingers that hold Holofernes’ head, and the spatter of blood on Judith’s right temple. Subtle, but terrifying.

See the Bible text for this story

‘Judith and her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes’

Orazio Gentileschi, (father of Artemisia), 1610-12

The deed is done – Judith still holds the sword in her hand. Now the fearful women stop to listen, to see if an alarm has been raised.

Orazio Gentileschi seems to have been more interested in the woman themselves than in the violent crime they had committed. These two women are not idealized beauties but real people, both with their own personalities and agendas.

This makes the painting sharply different from many of the others completed at that time, and may have something to do with the rape of his daughter Artemisia Gentileschi.

Artemisia was a real person to her father, not just an unnamed victim of crime.

See the Bible text for this story

‘Judith in the Tent of Holofernes’, Johann Liss, 1622

Judith has cut off the head of Holofernes and looks back over her shoulder, out towards the viewer. Her expression is strange – dazed, almost detached. She and her servant Alba are placing the severed head in a basket.

Caravaggio’s influence is clearly evident in Liss’s painting – the sumptuous flesh tones, lavish fabrics and dramatic lighting. The twisted gold fabric draws the eye upward towards Judith’s naked back and the ambiguous glance she casts over her shoulder.

Holofernes’ hapless body pushes out into the foreground of the painting.

An unusual feature of the painting: Judith’s servant Abra is African, not Jewish as you might expect.

See the Bible text for this story

‘Judith Beheading Holofernes’, Artemisia Gentileschi, circa1612

This is a rare depiction of something other paintings ignore: the fight that Holofernes may or may not have put up when he was being murdered. Here, in the moment of dying, he presses his right hand up against his assailant, attempting to fight her off.

Judith’s body seems to flinch away – from Holofernes? or from what she is doing? Both, perhaps.

This painting was made at about the time that Artemisia Gentileschi was raped by her tutor, the Tuscan painter Agostino Tassi. There is obviously a certain amount of personal relish in the painting, with underlying themes of castration and impotency.

The story of Judith must have appealed to Gentileschi, depicting as it did the triumph of female guile over male force.

See the Bible text for this story

‘Judith and the head of Holofernes’, Giovanni Baglione, 1608

The body of Holofernes, now separated from his head, seems to writhe in its death throes. A rather winsome Judith has grasped the head by its hair and is moving away from the couch. Her maid looks back in horror at the body.

Contrast this image with Caravaggio’s (above). Judith seems remarkably tranquil in the circumstances, while her maid registers shock and horror.

But note in particular the different treatment of Holofernes’ body. Here in Baglione’s painting the body itself is almost hidden. What we can see of it is distorted and writhing, the head quite separate from the body – altogether, a figure of horror.

See the Bible text for this story

‘Judith and her Maidservant With the Head of Holofernes’

Artemisia Gentileschi, circa 1625

Judith has killed Holofernes, and now her maid Abra crams the bloody head into a sack, to carry it back to Bethuliah. But they seem to have heard something, and pause, waiting to see if they have been discovered.

If they have, they know they will die too.

The tension of the scene is almost palpable. Danger is close as Judith and her maid Abra gather up the severed head of Holofernes, preparing to flee from the enemy camp, back to safety in Bethulia. The light and shadow emphasise the imminent danger as Judith and Abra prepare to flee Holofernes’s tent with his severed head.

We can almost smell and feel their fear.

See the Bible text for this story

‘Judith with the head of Holofernes’, Cristofano Allori, 1613

Judith has hacked off the head of Holofernes and now puts away the sword she used to do the deed. Her maid Abra leans anxiously towards her, protectively, urging the dazed Judith to move with more speed.

The head of Holofernes is said to be a portrait of the artist, and the woman in the picture was modeled on his mistress, a famous beauty called Mazzafirra.

Perhaps the painting is a comment on the balance of power within their own relationship – she having conquered him and now holding him helpless in her grip. His face is already drained of color, a dramatic contrast to the rich material of her robe.

See the Bible text for this story

Judith with the head of Holofernes, stained glass window

Diane-Blair Goodpasture, 2010

Judith holds the recently severed head of Holofernes by its hair. His sword, which she used to kill him, is smeared with his own blood. Her dress, too, is spattered.

An ignoble end for a famous warrior, killed by his own sword.

Judith is lavishly dressed, with a jewelled head-dress enclosing her thick hair. Compare the two faces: hers blank – with shock? His ghastly in death.

Behind Judith are two things: the all-seeing eye of God, and the Hebrew letter ‘yod’ which is symbolic of the name of God – Marc Chagall uses this same device in his paintings.

See the Bible text for this story

‘Judith with the head of Holofernes’, Titian, circa 1515

Judith has cut off the head of the enemy general Holofernes, and now prepares to carry it back to the townspeople of Bethuliah.

There has been some argument about the identity of the woman in this painting. The confusion arose because the decapitated head is carried on a silver platter, traditionally the way that John the Baptist is depicted. This would then make the woman Salome.

But the adoring expression on the face of the second woman suggests that she is Abla, Judith’s servant, and this seems more likely.

It is generally accepted now that this is, in fact, a painting of Judith, done at the beginning of Titian’s career.

See the Bible text for this story

‘Judith’, Vicenzo Catena, 1520

This painting of Judith is quite different to most others on the subject. She is dressed in white, the color of chastity, and the sword stands firmly between her body and Holofernes’ head.

The picture contains a message about her chastity, which the Bible says she retained despite every effort on Holofernes’ part to seduce her.

This is no seductress, but a determined heroine.

See the Bible text for this story

Save

Save

Judith in the Bible – links

When Judith came into the tent and lay down on the sheepskins, Holofernes was besotted. He offered her something to drink, but she drank only the wine given to her by her maid – was it watered down so she could stay sober? Holofernes, on the other hand, got down to some serious drinking.’

Sex, lies, murder…

Nebuchadnezzar was the King of Babylon, and ‘Babylon’ became code for depravity, cruelty and paganism.

Nebuchadnezzar is mentioned in the Bible because he met and terrified King Jehoiakim of Judah, who paid tribute to him and acknowledged him as Judah’s master. Of course, Jehoiakim had little choice in the matter – Nebuchadnezzar’s resources were immense, and little Judah stood no chance at all against him.

The Israelites were at a disadvantage because the Philistine overlords did not allow them to have metal-working facilities. This meant they could never have weapons that matched their enemy’s. If they had swords, they were always inferior to the ones wielded by their adversaries, and could only be used as backup weapons.

When at the climax of any siege the defenders on the battlements were unable to hit the enemy at the foot of the walls without exposing themselves dangerously to the attackers’ missiles, the men posted on the towers could shoot along the walls from relatively secure positions.

At great personal risk she went into the enemy camp of Holofernes. He had a fearsome reputation, but she charmed him, holding his sexual advances at bay.

Read more…

She came close to his bed, took hold of the hair of his head, and said, ‘Give me strength today, O Lord God of Israel!’ Then she struck his neck twice with all her might, and cut off his head.

Read more…

‘Judith with the head of Holofernes’, Titian, 1570

Judith has cut off the head of Holofernes and now picks it up by its hair, to lower into the bag held by her maid Abra.

This is a painting made by Titian towards the end of his life. His Judith is a luminous, serene beauty assisted by a black servant woman.

The head of Holofernes is truly terrifying, a dark and gruesome trophy for the Judean inhabitants of Bethuliah.

Bible reference: Judith 13:9-10

Returning to Bethuliah

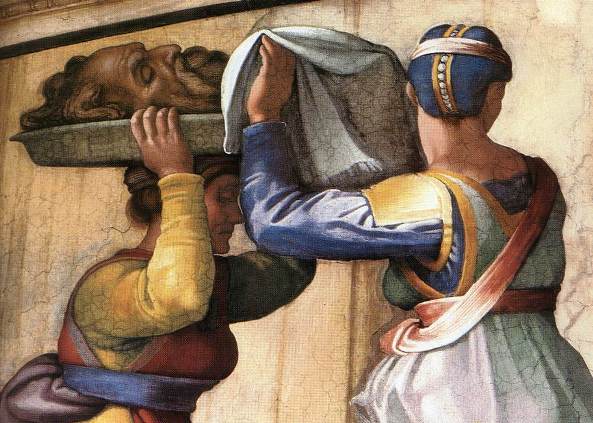

‘Judith carries away the head of Holofernes’, Michelangelo Buonarroti, 1508-1512

Below: Detail of Judith and Abra with the head of Holofernes

Holofernes’ lifeless body lies in the background as Judith and Abra hurry away from the scene of the murder. Abra carries the grisly head on a tray/basket, and Judith tries to cover it from sight.

This is part of the painted ceiling in the Sistine Chapel.

When he came to choose images for the Chapel, Michelangelo seems to have focused on heroic deeds, or on seminal moments in the story of God’s unfolding plan.

He saw Judith as one such hero, leaving the obscurity of her life as a widow in a small city to undertake terrifying actions that would ultimately save her people.

Bible reference: Judith 13:9-11

‘Judith’, Giorgione, 1504

Unlike the other paintings of Judith, this one does not show a particular moment in the story.

- Holofernes has been killed, but Judith is not in the process of returning to Bethuliah as she subsequently did.

- The head is not wrapped up, or being displayed on the city walls, but is simply a trophy taken in battle.

The battle of the sexes? The painting is more like a portrait of Judith as a goddess of sexual love – see Giorgione’s ‘Sleeping Venus’ for a similar image of idealized beauty.

See also Bible Heroines: Judith

Georgione’s image of Judith contrasts dramatically with other paintings of this subject. She is remote, untroubled, serene – a goddess, not a human woman who has just committed violent murder.

In the background is a landscape, reminiscent of the country round Castelfranco, which the artist knew as a boy, and loved all his life.

Giorgione died young, probably of the plague in Venice, but his works have remarkable maturity and a certain enigmatic quality. Could not this ‘Judith’ be likened to a profane Mona Lisa?

Biblical reference: Book of Judith

‘Judith with the Head of Holofernes’,

Elisabetta Sirani (1638-1665) circa 1660

Judith has returned to Bethuliah, and now draws the head of Holofernes out of the sack her maid has carried. Two attendants run to light her way with torches.

Now all the townspeople and all the enemy soldiers can see that the much-feared Holofernes is really dead.

Elizabeth Sirani came from a prominent family of artists – her father was Giovanni Adrea Sirano, principal assistant of Guido Reni. She died at the early age of 27. She has placed Judith in a medieval setting – note the ramparts of a city wall (Bethulia) in the background.

Biblical reference: Judith 13:15

‘Judith’s Return to Bethulia’, Alessandro Botticelli, 1470

Judith has completed her mission and returns to Bethulia, sword in hand. Her maid Abra follows with Holofernes’ head, wrapped up and carried on the woman’s head.

Judith has the air and demeanor of a goddess, rather than a mortal woman. She strides across an idealized landscape sword in one hand, olive branch in the other. She will live in peace if she can, but is prepared for war if it is forced upon her.

It is interesting to compare Botticelli’s Judith and Abra with the figures in his more famous ‘Spring’. There is the same sense of detached majesty at the center of the painting.

Judith dominates all around her – and reinforces her power by carrying a rather nasty-looking sword. Yet, as in the ‘Spring’ painting, the overall impression is of fluid beauty and movement.

For more on the unfortunate Nebuchadnezzar, see Bible Villains: Nebuchadnezzar

Bible reference: Judith 13:10

Save

Save

Judith, by Anthony Hecht

It took less valor than I’m reputed for.

Since I was a small child I have hated men.

Even the feeblest, in their fantasies,

Triumph as sexual athletes, putting the shot

Squarely between the thighs of some meek woman,

While others strut like decathlon champions,

Like royal David hankering after his neighbor’s

Dutiful wife. For myself, I found a husband

Not very prepossessing, but very rich.

Neither of us interested in children.

In my case, the roving hands, the hot tumescence of an uncle,

Weakened my taste for close intimacies.

Ironically, heaven had granted me

What others took to be attractive features

And an alluring body, and which for years

Instinctively I looked upon with shame.

All men seemed stupid in their lecherous,

Self-flattering appetites, which I found repugnant.

But at last, as fate would have it, I found a chance

To put my curse to practical advantage.

It was easy. Holofernes was pretty tight;

I had only to show some cleavage and he was done for.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Judith’s story: Off With His Head!!

Who was Judith? Judith was a wealthy and beautiful young widow living in a hilltop town called Bethuliah. During a siege of her town, she undertook a daring sexual mission to save her people from annihilation.

At great personal risk she went into the camp of Holofernes, the Assyrian commander-in-chief of the enemy forces. He had a fearsome reputation, but she charmed him, even managing to hold his sexual advances at bay (maybe…)

How did she kill Holofernes? Once she had lulled him into a sense of security she tempted him into getting drunk. Then she took his own sword down from where it hung on his bedpost, and hacked off his head as he lay in a stupor.

With his head wrapped in the bed curtain, she returned triumphantly to her own people in Bethuliah.

What did she do with his head? The head of Holofernes, hung on the town ramparts, caused panic among the Assyrians who fled in great disorder.

Her story is similar to the David and Goliath story, where a seemingly weak person overcomes a person of superior strength by calling on God’s help and using cunning and intelligence.

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher