Who was Tamar?

- Tamar married, but was childless. Tamar married into the family of Judah, first to Judah’s son Er and then, after his death, to Onan his brother. Because Onan practised a form of contraception, Tamar did not become pregnant. For a Jewish woman this meant disgrace, because people thought that being childless was a punishment from God. Read Genesis 38:1-11

- Tamar claimed her Levirite rights. God punished Onan and he died. By law Tamar should then have married Judah’s third son so she could have a baby who would inherit her dead husband’s share of the tribal wealth. But this did not happen, so she decided to get justice for herself. She dressed as a prostitute, had sex with her father-in-law Judah and conceived twin sons. Read Genesis 38:12-19

Newborn twin babies

- She was accused of promiscuity. Because she did not name the father of her child, it was assumed she had been promiscuous, and Judah sentenced her to burn to death. But she saved herself by a clever ploy. Read Genesis 38:20-26

- She bore twin sons. God rewarded her tenacity with the birth of sons, one of whom was the ancestor of King David, Israel’s great hero. Read Genesis 38:27-30

Tamar marries, but remains childless

Genesis 38:1-11

The Empty Cradle

As a young woman, Tamar married Er, eldest son of Judah and an unnamed daughter of Shua. It was a good match and things should have gone well, but Er practised some form of birth control, probably by withdrawing before ejaculation, and so Tamar was childless. God punished Er – people at the time saw withdrawal as a crime against Nature and God. Tamar suffered a double tragedy: her husband Er died, and she lost the chance of having a child.

‘Er, Judah’s firstborn, was wicked in the sight of the Lord, and the Lord put him to death. Then Judah said to Onan ‘Go into your brother’s wife and perform the duty of a brother-in-law; raise up offspring for your brother.’

Read Genesis 38:1-11

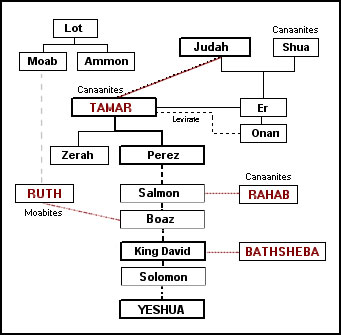

Genealogy of King David and Solomon, and of Yeshua (Jesus of Nazareth); Tamar was one of the foremothers of both these leaders

Widowed and without children, Tamar was low in the pecking order of the tribe. But there was a way out: the Levirate Law. This law was found in Deuteronomy 25:5-10. If a man died, and his wife had not yet had a child by him, she could go to his brother and demand that he marry her and give her a child who would inherit the property of the dead husband.

This practical law was about

- providing for all members of the tribal family, whether their fathers were alive or not

- a woman’s right to have children.

Under Levirate law, Er’s younger brother Onan was obliged to give Tamar a child. But he refused outright to do so, probably because it meant his future share of the inheritance would be less. Any child born to Tamar would carry Er’s name, not Onan’s, and would inherit Er’s portion of the estate. Onan practiced the same form of birth control, and Tamar did not conceive.

Onan was guilty on two counts:

- he failed to carry out the Levirate obligation to Tamar and

- he disobeyed his father’s command.

God punished Onan. He died, and his death at such an early age was seen as just punishment. Since then, ‘onanism’ has become the technical word used to describe uncompleted coition and masturbation.

A pair of leather sandals

Deuteronomy 25:9-10 describes the punishment for a man who refused to obey the Levirate law. It was public and confronting. The woman, the injured party, went up to him in a public assembly, pulled his sandal from his foot, spat in his face, and said ‘This is what is done to the man who does not build up his brother’s house’.

To us the punishment does not sound very much, but in the context of the time it meant public disgrace that could not be lived down. The action involving the sandal had symbolic meaning: the foot symbolized the male genitals, the sandal the female sexual organs, and the spittle, the semen.

The woman’s action publicly humiliated the man, and his family’s disgrace was remembered long after he was dead. Public shame was often used to enforce the law in ancient times.

When Onan died without giving Tamar a child, she looked to the third son of Judah to be her husband. But this boy, Shelah, was too young to be a father. So Judah sent Tamar back to her family, promising to send for her when Shelah was old enough.

It may have been that Judah really meant to carry out his promise, but as time went by he became convinced Tamar was a jinx, bad luck, responsible for the deaths of his two eldest sons.

Tamar claims her rights

Genesis 38:12-19

Tamar waited patiently, but after a while it became clear that Judah did not mean to give her his third son Shelah as a husband. Judah refused to keep the Levirate law.

When she saw that she was to be left a childless widow, Tamar decided to act. She intended to get what was rightfully hers. She would trick on Judah, just as he had tricked her. The deceiver now became the deceived.

She dressed in the special clothing of a prostitute which included a veil across her face that disguised her identity, waited for Judah at the city gates (see below), and persuaded him to have sexual intercourse with her.

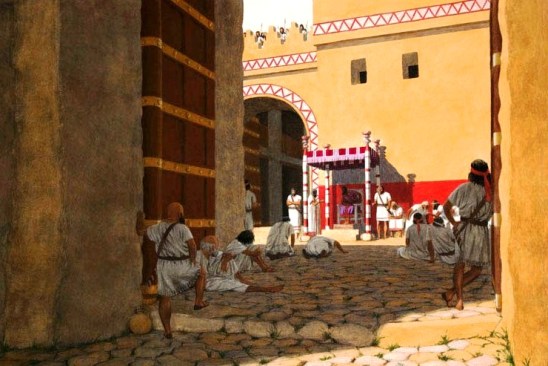

Reconstruction of ancient city gates

The city gates were something like the reconstruction above: massive mudbrick walls with a strong gateway that could be shut tight against an enemy, or closed at night for security. Here the townspeople congregated to carry on the city’s business. Here also the city prostitutes waited for customers. No respectable woman would sit there, or be there alone.

‘Tamar put off her widow’s garments, put on a veil, wrapped herself up, and sat down at the entrance to Enaim, which is on the road to Timnah. She saw that Shelah was grown up, yet she had not been given to him in marriage. When Judah saw her he thought she was a prostitute, for she had covered her face.’ Read Genesis 38:12-19.

It is possible, though unlikely, that Judah perceived Tamar as one of the sacred prostitutes. The Hebrew words for a sacred prostitute (kedeshah, sacred woman) and a normal prostitute (zonah) are both used in this story. In Israel, prostitutes were required to cover their faces at all times.

This extraordinary picture by Kevin Rolly adds a new dimension to the story of Tamar and Judah; the recently widowed Judah, gripped by grief at the loss of his wife, still wears his wedding ring

Tamar may have followed a version of this practice, but she also asked for payment from Judah. He promised to send her a kid from his flock, and in the meantime, as a guarantee, he left his seal, cord and staff, all of which were personal items that could be identified. Judah decided on the fee, Tamar on the pledge.

Ancient cylinder seal

Then she took off the special clothing of a prostitutes, dressed herself again in her widow’s clothing, and returned home.

The seal, cord and staff were symbols of a man’s identity, items of great personal worth, and it is astonishing that Judah gave them up. Judah’s seal may have been a cylinder seal similar to clay seals found in a number of archaeological excavations, particularly in the Mesopotamian area. Herodotus gives a description of the staff made specifically for each person, with a personal emblem carved on the top of it.

Carved wooden staff

It is even more astonishing that Judah gave up his staff. This was not simply a length of wood used for walking. The tribal leader’s staff was an emblem of authority, something like a royal sceptre. It had the lineage of the leader carved into it, the names of his forebears.

Judah’s handing over of these items show the disordered state of his mind at this point in his life, after the death of his wife and sons. He was not thinking clearly, or acting wisely.

Tamar saw the cord, seal and staff in quite a different way: they symbolised the son she intended to have, the son who might succeed Judah.

This famous incident has been recorded by a number of painters; see Bible Art: Tamar for their work.

Tamar is accused of promiscuity

Genesis 38:20-26

When Judah’s friend came to make payment to the unknown prostitute and reclaim Judah’s seal, cord and staff, the woman was nowhere to be found. Tamar had gone home, without telling anyone who she was. But through this one act of sexual intercourse with Judah she became pregnant, a fact that was soon evident to the people around her. Judah, who already blamed her for the deaths of his sons, thought the worst when he heard that she was pregnant. She was accused of ‘playing the whore’.

And Judah said “Bring her out and let her be burned”.

And Judah said “Bring her out and let her be burned”.

Judah, as head of the tribe, had the right to pass judgment on her, and to condemn her to death. The Code of Hammurabi, Law 129, reads ‘If the wife of a man has been caught while lying with another man, they shall bind them and throw them into the water. If the husband of the woman wishes to spare his wife, then the king in turn may spare his subject’.

Deuteronomy 22:22, the Hebrew law code, recommends death for both the man and the woman.

Judah pronounced that Tamar should be burnt to death, a particularly cruel way to die. But Tamar was not finished yet. She sent the seal, cord and staff back to Judah, with the message that they belonged to the father of her child, and Judah, confronted by the evidence, had little choice but to acknowledge that she was in the right, that she had been acting according to the law.

The birth of Tamar’s twin sons

Genesis 38:27-30

When Tamar went into labor she was the center of a tight little band of kinswomen and villagers: a midwife, her relatives and her friends. She knew what to expect, having seen other village women giving birth.

Childbirth in ancient times

Tamar’s insistence on her rights was rewarded by the birth of not one but two children!

‘While she was in labor, one baby put out a hand; and the midwife took and bound on his hand a crimson thread, saying “This one came out first”. But just then he drew back his hand, and out came his brother; and she said “What a breach you have made for yourself!” Therefore he was named Perez.’

These twins were jostling for position even before they were born. The theme of a brother pushing ahead of his elder sibling is a common motif in Genesis.

Crimson thread bracelet

Tamar’s sons were called Perez and Zerah. Perez would be an ancestor of King David.

Tamar’s actions were unorthodox by modern standards. But in a way she ‘redeemed’ Judah. She saved him from doing what was wrong, and was thus a pre-figure of Jesus, who was one of her descendents.

Tamar: claiming her rights

Tamar covered her face

with a veil

Tamar means ‘date palm’, source of food, shade, life

Judah means ‘give praise to God’

Er was Tamar’s first husband; Er spelt backwards in Hebrew is the word for ‘evil’

Perez means ‘he who pushes through’, breaks through a wall; Zerah means ‘scarlet’

Onan means ‘the virile one’ – this is ironic, since he refused to give Tamar a child

Main themes of Tamar’s story

- God’s promise to continue the Jewish people through many generations. This is one of the main themes of the Book of Genesis, and Tamar’s story is a central example. None of the people in this story understood God’s long-term plan for the Jewish people. They saw only their own predicament. But the mind of God had a plan of which they knew nothing.

Date palm, heavily loaded with clusters of dates; dates were a symbol of fertility

- Bad things happen to good people, but good can come from evil, even when we cannot see God’s plan or understand it.

- The quest for social justice. The story lays the foundation for the continuing Jewish preoccupation with social justice. Despite Tamar’s unorthodox methods, she was a woman of integrity who risked her life to fulfill her duty to herself and her family. She knew she had the right to a child, and she knew that her first husband Er had the right to an heir. Once again, God’s plan unfolded through the unorthodox actions of a woman.

Tamar is one of the four female ancestors of Jesus, in Matthew’s gospel. All four had irregularities in their marriages/sexual relationships. For more on this see The Ancestors of Jesus

Read about

other fascinating women of the Bible

Bible Study Resource for Women in the Bible: Tamar, the Levirite Law, and Judah

Tamar links

Ancestors of Jesus

Ruth, Tamar, Rahab

& Bathsheba

Having a baby

– or two

Childbirth

in ancient times

Movies often tell a story like Tamar’s, where the heroine has to adapt to an unwelcome situation. In ‘Hobson’s Choice’ an enterprising young woman makes the best of a bad situation, and ends up happy and in love. Can you list some other movies with similar themes?

Sexually charged moment when Tamar meets Judah: famous paintings of this story

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher