Who was Mary of Nazareth?

It depends on which Mary you’re talking about. There were two:

- a Jewish peasant girl living in a backwater province of the Roman Empire, and

- the semi-goddess Virgin Mary, in Christian churches all over the world.

This page describes the first one.

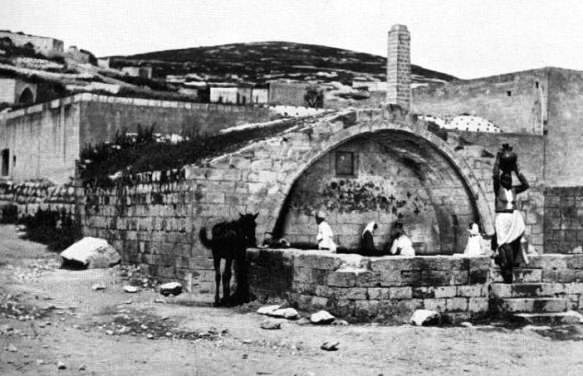

19th century photograph

of a young Bedouin girl

What did Mary look like?

- Mary, the future mother of Jesus of Nazareth was a young peasant girl, probably less than five feet tall, with glossy black hair oiled and parted in the center, the center parting painted with red or purple dye.

- She’d have been robust, sturdy, with plump little breasts and strong brown hands callused from work.

- Her teeth would have been good, maybe better than ours, since the only type of sweeteners she’d get came from dried fruit – or at least from sweet syrup made from figs or dates. Sugar was unknown and honey was a luxury item she would probably never taste.

Mary’s jewelry?

There were heavy gold earrings swinging from her ear lobes – an important part of her dowry, so they’d be as flashy as her family could manage.

There might be a gold nose-ring as well, though you’re unlikely to see this on any statue of the Virgin. A Jewish peasant girl needed to make an impact with the way she looked – lumps of gold at her ears showed she was a respectable girl from a decent, established family.

What were Mary’s clothes like?

Her clothes were made from homespun wool or linen, which she wove herself. The dress fell in a practical loosefitting design, in one of the soft colors produced by natural dyes – cream, a deep faded pink, a soft blue-grey, or light brown.

The fabric and weave depended on the season – heavy wool for winter, light wool (or linen, but only if you were rich) for summer. The long skirt got tucked up into the waistband when she worked.

There would be folds in the fabric, from where the garment had lain in one of the storage niches in the wall of her house.

Handwoven fabric and tribal-specific embroidery were common

in 1st century Palestine

Was there embroidery or smocking on the front yoke of the dress? Most probably. The women of the eastern Mediterranean had been famous for embroidery for hundreds of years.

The woven belt she wore round her waist was probably stiff with embroidery too, geometric designs, circles, colored edging, all in the same soft colors. Brighter colors came from expensive dyes she could never afford.

She wore leather ankle-length boots in winter, sandals in summer, and cut her dusty toenails with a sharp knife.

The gift of speaking well

The language she spoke was Aramaic. It’s a poetic language, and if you’ve ever heard the prayer her son composed, the Our Father, said aloud in Aramaic, you’ll know Jesus was a gifted poet. The alliteration and rhythm of the words are lovely to hear.

But Mary spoke it with a broad Galilean accent, disdained by the sophisticated Jerusalemites.

19th century photograph of a Middle Eastern girl

She could talk the leg off an iron pot. Being able to talk well has always been a valued skill among Jews. Have you ever listened to Jewish mothers in New York prodding their children into constant talk – ‘are you sure about that? Why do you think that? And what did you say then? Tell me why you did that….’ This question and answer barrage goes on from morning to night. No wonder Jewish children grow up with the ability to argue a point. They’ve learnt it from birth.

Mary would have been the same. Hers was an oral society where stories, prayers and poems were learnt off by heart, rather than read. The great enemy in ancient societies was boredom. Story-telling and clever talk were ways to keep boredom at bay. Good talk was a major way to pass the time.

Being able to entertain people made you valuable – since everyone got bored at some time or other before the print media was invented.

Women in rural communities like the town of Nazareth did not read. It was unnecessary.

Men had to learn to read because they were commanded to know the Torah, but it was seen as a specialized skill, something that men did, not women. In point of fact, any story is better when told with nuance and wit.

What the modern world has forgotten is that the Scriptures were entertaining. People in the ancient world told stories and acted them out for pure enjoyment. There is, after all, more sex and violence in Scripture than in anything that has come out of Hollywood.

You don’t believe me? Read Judges 19a – the Levite’s concubine or Genesis 38 – Tamar seduces Judah, for a start. Then imagine the stories acted out with gusto. That was entertainment.

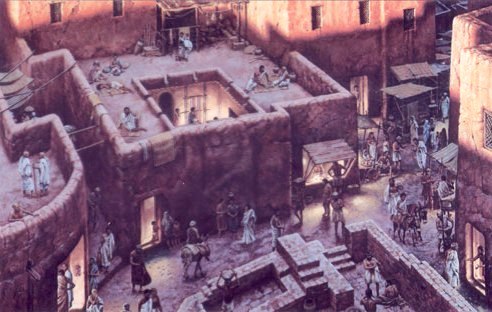

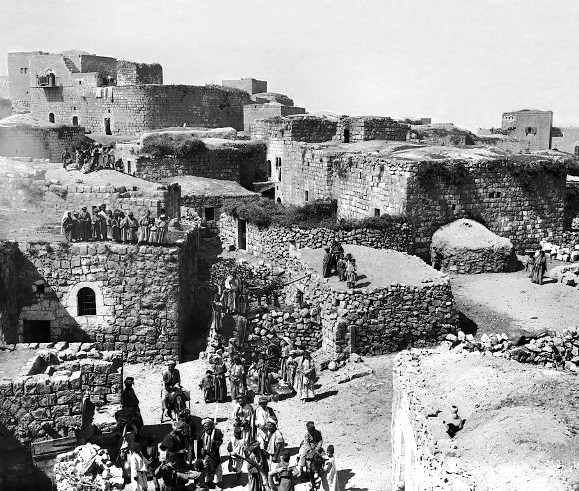

What did Mary’s village look like?

It has to be said that the little village of Nazareth, on the dreary outer fringes of the Empire, was not an attractive place. Hot and dusty in summer,  cold and muddy in winter, there was not much to recommend it. The streets were narrow, impossibly so by our standards. It was a squeeze to get a laden donkey through. Carts went around the village rather than through it.

cold and muddy in winter, there was not much to recommend it. The streets were narrow, impossibly so by our standards. It was a squeeze to get a laden donkey through. Carts went around the village rather than through it.

We know how tiny it was because of the tombs excavated there. Tombs were always placed outside the village limits, so by looking where the tombs were, you know the outer limits of the village.

If you liked people – there were about 400 in Nazareth when Mary lived there – the limited space could be an advantage. You were never more than a few feet from someone else. You knew their business, and they knew yours.

Why am I mentioning this? It’s important to keep this lack of privacy in mind when we talk about the circumstances of Mary’s pregnancy.

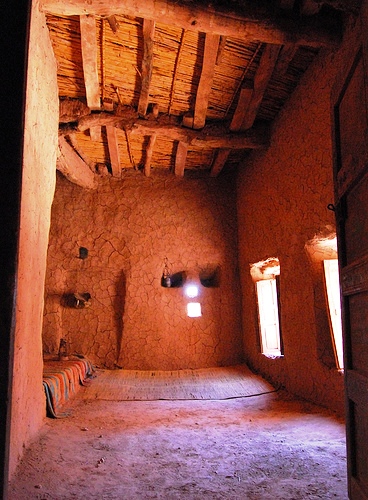

What sort of house did Mary live in?

The mud brick houses were blank-fronted, with small high windows and an occasional wooden door.

Most houses had, as a minimum, a courtyard and two rooms – a front, public room with an awning, and a private room behind it.

The flat roof above these, with exterior stairs, was used as an extra room, with awnings of thick woven goats’ wool to protect against the sun.

Interior of a clay brick house

with wooden roofing

Inside, the rooms were quite comfortable, though Spartan by our standards. There were raised platforms at one end of the room, covered with cushions and mats – woven by the women and embroidered with intricate patterns.

The walls were covered with plaster, rubbed flat with a stone and painted with geometric patterns.

Was there any furniture?

There was hardly any furniture as we know it. Niches were cut into the mud-brick wall, and these provided storage space for bedrolls and clothes. Large amounts of food – jars of oil and olives, etc., were kept in a separate storage area, made secure against mice.

A village the size of Nazareth could never have supported a full-time carpenter (as Joseph is said to have been) for any length of time. Anyone in this trade would have needed to travel elsewhere to find steady employment.

As well as the buildings above ground, archaeological excavations show there was a honeycomb of underground rooms under the houses, hollowed out of the rock. They were used for a variety of purposes – living quarters in the fierce heat of summer, cisterns for water, grain silos, and storage.

Who was in Mary’s family?

Mary lived in an extended family.

There were at least eight or ten people sharing the house. The nuclear family of today simply did not exist. It would not have worked. There were too many tasks that needed several people working together.

Note: Maybe that was not such a bad thing. I remember my daughter-in-law coming to stay with us, bringing her three-month old baby. There were three women in the house – my daughter, the young mother, and myself. We shared the tasks between us. In the afternoon, when the baby was most likely to be fractious, the young mother would go for a walk or have a rest. My daughter would take the baby, walking him, patting him and talking to him. I would cook tea. By mealtime, the food was cooked, the mother was relaxed, and all of us felt that things were as they should be. The men were happy with the situation too. I got satisfaction from knowing I was useful; my daughter was happy to take over another woman’s child for a few hours; and the young mother knew she was not alone in caring for her baby.

We are so accustomed to paintings of a solitary Mary or a three-person Holy Family that we forget that Mary came from a large family/community in Nazareth

Mary and the women in her family worked together in much the same way, sharing everything.

Her work was not limited to the house. Galilee, where she lived, was the breadbasket of the Jewish kingdom. There were orchards, olive-groves and vineyards to be tended, and of course the grain crops planted and harvested yearly. The women did a lot of the work in the fields.

Menstruation – girl into woman

When she was about 11 or 12 years old, Mary began to menstruate. This meant she was of marriageable age, in Aramaic a betulah. The corresponding word in Hebrew, the ancient language of religious texts, is almah.

Note: remember this word. It means ‘young woman of marriageable age’ – possibly a virgin, but not necessarily so.

The first menstruation was a big milestone in any girl’s life, and in Mary’s case it would have been celebrated with a party – to let everyone know she was now ready for marriage.

She would have been introduced to the special customs that Jewish women followed at the time, particularly those relating to menstruation.

During her menstrual periods, a Jewish woman was relieved of many of her normal duties.

- She was not required to draw and carry water from the well,

- or cook and serve food to members of her family.

- She did not have to go to the marketplace.

- If she was married, her husband could not approach her for sex.

The days of her menstrual period were regarded as time out, time for herself. On these days, relieved of the mundane activities of her normal daily life, she has time to think and rest. Ah, the good old days.

There were purity laws for men too. Men had to wash themselves and change their clothes whenever they have any sort of sexual emission, spontaneous, as in a wet dream, or deliberate, in sexual intercourse.

The design of a mikveh has remained virtually unchanged for many centuries

What is a mikveh?

After her menstrual cycle, a woman in 1st century Galilee was required to bathe herself from head to toe in a special pool of clean water, called a mikveh (see at right the ancient mikveh excavated at Masada).

Each small community had its mikveh, and towns and cities had large numbers of them, some public, some private.

The mikveh pool was built a special way, so it had

- enough headroom under water to allow complete immersion,

- an additional tank for gathering clean rain-water, and

- a small pool at the entrance for washing hair, hands and feet before entering the main pool.

Do you remember the story of King David watching, hidden, while the beautiful Bathsheba (whose husband was away with the army) took her bath? The whole point of the bath in this story is that she must have just finished menstruating, so she’s not pregnant at this point, so the baby she had later on must have been King David’s…..

In any event, the washing of a woman’s body was a tangible way for the woman to renew herself, refresh herself.

It wasn’t a bad idea in terms of hygiene, either. It meant that every adult had to wash himself or herself, wash their clothes, and put on clean clothes at regular intervals. The cleanliness of Jewish women benefited the whole population.

Ancient people did not know about bacteria, but they were aware of the connection between dirt and disease. The religious ritual of the mikveh lowered infant mortality, and kept Jewish mothers healthier.

Mary’s marriage is arranged

A young bride being prepared for her wedding: painting by Frederick Goodall

Now that Mary’s menstrual periods had started, serious consideration was given to the choice of a husband.

It was taken for granted that she would marry. God had given the commandment to ‘be fruitful and multiply’ to Noah, and so Jews believed it was their duty to marry and produce children. Any person who had passed the age of twenty without being married had not carried out the will of God – which makes you wonder about Jesus, and whether he was married or not, or who he might have been married to. But that’s another story….

Mary’s whole family joined in the selection of an appropriate husband. After all, it was something that wouldl affect them all. This was not a nuclear family living by itself in a separate house. This was an extended family, where any new member had to be acceptable to everyone – or there could be trouble down the line.

Mary’s family had to be sure she was marrying someone whose family and way of life would fit in with hers. She would be living and working with these people for the rest of her life, so they must be people she would get along with.

What sort of person was Mary hoping for?

A young Galilean woman would hope for someone

- round about her age. An old husband and a young wife spelt trouble

- someone with enough money and goods to give her comfort and security

- physically attractive; Jews believed a happy sex life was one of the gifts God gave to a married couple

- someone from a reputable family; there must not be any scandal or bad blood attached to his family

- A student of the Scriptures; scholarship meant a man was intelligent, prepared to work, and able to think

That’s the shopping list for a young girl in 1st century Palestine.

Mind you, there was not a lot of choice in Nazareth, since it’s estimated that there were only about 400 people there altogether. So the person her parents suggest to her was probably someone she’d known all her life, and always half expected to marry.

He was also probably related to her in some way, though not too closely. Joseph was his name.

Joseph, Mary’s prospective husband

Joseph was a young man, not much older than she was, and well-regarded by the people of Nazareth. We know this because Matthew’s gospel call him ‘just’ or ‘righteous’, and the Gospels don’t bandy adjectives round without good reason.

His name ‘Joseph’ is one of the most popular Jewish male names of the time. Nine first names made up 44% of the male population in 1st century Palestine, and Joseph was in the first three on the list.

He was a builder, not a carpenter, if he lived continuously in Nazareth. But if he had already moved out and worked in nearby Sepphoris, a much larger town than Nazareth, or moved to any of the other great building projects that King Herod the Great had under way, he might have been a carpenter.

The marriage contract

A marriage contract would have been worked out between the families of Mary and Joseph. In theory, this was done by the male heads of family, but in practice a good deal of the power in Jewish families lay with the women, and nothing was likely to go ahead unless they said so.

In any case, an agreement was reached, and the engagement went ahead – again with a big party.

Ancient dowry necklace from the Middle East

The betrothal was a formal agreement to marry, settled with the transfer of property from the young man to the girl. Sometimes it was a substantial amount, sometimes a token. It was usually returned to the husband when the formal marriage took place, as a contribution to setting up a new family.

What about Mary’s dowry?

The dowry was a separate matter. This was property handed over by the girl’s family at the time of her marriage, and afterwards owned by the wife. It was her share of the family inheritance, enough to act as an income for her should she be abandoned or widowed.

There were complicated laws regarding payment and ownership of the dowry. In neighboring Mesopotamia the dowry could be inherited only by the woman’s sons, not by any of her husband’s family. This was a precaution against the dowry being used to enrich the husband’s family.

In Rome the dowry was paid in three annual installments after the marriage. If her husband died or was the guilty party in a divorce, the wife reclaimed the entire dowry. In the later Empire, she could reclaim the dowry even if she was the guilty party.

Mary’s betrothal to Joseph

The betrothal of a young couple had to be public, witnessed by many people. Part of the ceremony in Galilee could involve the young man picking up the young woman and placing her on a donkey or on some other means of transport like a boat or a cart. At this stage, there was no sexual contact.

People in the ancient world knew it was dangerous for a woman to give birth before her young body was properly developed. She could be a permanently disabled. So marriage was deferred, usually for about a year.

But the engagement went ahead, and this agreement/contract was so binding in Galilee at this time it could only be broken by a formal divorce.

Mary was pregnant. What then?

The next thing we know, Mary was pregnant. Her normal menstrual periods stopped. This can be hidden for quite a while in the modern world. But in Mary’s time, when a whole family lived and slept in one or two rooms, the fact that a young girl’s periods had ceased was noticed immediately.

A woman in 1st century Palestine, and in fact until quite recently, needed a whole stack of equipment to cope with her menstrual flow. There had to be a pile of absorbent cloths, usually of wool or linen, and the tapes or belts to keep them in place.

Every month when she had her period, a woman took the piece of cloth, folded it lengthwise and tied it up between her legs so that it soaked up the menstrual fluid.

Every month when she had her period, a woman took the piece of cloth, folded it lengthwise and tied it up between her legs so that it soaked up the menstrual fluid.

Then, when the cloth was used, she put it into a leather bucket or a clay pot filled with water, to soak it clean. (The water, by the way, had to be carried from the well by another woman, since the menstruating woman was ritually unclean.)

After a day or so of soaking, she scrubbed her napkin clean and laid it out to dry on the flat roof of her house.

Having your menstrual period was highly visible.

When a young woman became pregnant, all this paraphernalia was no longer needed, since she was not producing any blood-stained napkins. It was immediately obvious to the women around her that she was either ill or pregnant.

So it would have been in Mary’s household. The other women, her mother, aunts and sisters, knew straight away that something was up.

Mediterranean families are not known for their reticence in such a situation. In the conservative Jewish family Mary belonged to, her pregnancy meant severe embarrassment if not outright disgrace to herself and all her family.

The secret may have been limited for a time to the women in the family. How long this particular secret could be kept depended on the personalities of the other women. Judging from later clues we have to Mary’s character, we can assume she came from a family of strong women.

Even so, the secret could not be kept indefinitely. Apart from anything else, the loose dress she wore was tied up with a wide sash, and her swelling tummy would eventually give the game away.

Who’s the father of Mary’s baby?

First, I’m taking it for granted that there’s a real, human father for her baby. No, I’m not abandoning the ‘conceived by the Holy Spirit’ idea. But I’d like to put it on hold for the moment. We’ll get back to it later.

These are the facts we know:

- Mary was pregnant.

- there had to be a human father.

- she was frightened, her family embarrassed, and the man, whoever he is, could not be named.

So who was he? There are several theories.

Shocking as the idea may be, he may have been a member of her own family. Statistics in the modern world show that pregnancies with an unnamed father usually come from the girl being interfered with by an older male relative.

Probably not much has changed in two thousand years. This is one possibility, however distasteful, that has to be faced.

Was Mary the rape victim of a Roman soldier?

Another theory, quite well argued, is that the father of her baby was a Roman soldier stationed in a nearby garrison center. On the face of it, this sounds far-fetched, something you read in a sensational tabloid. But there are some facts that make the theory at least plausible:

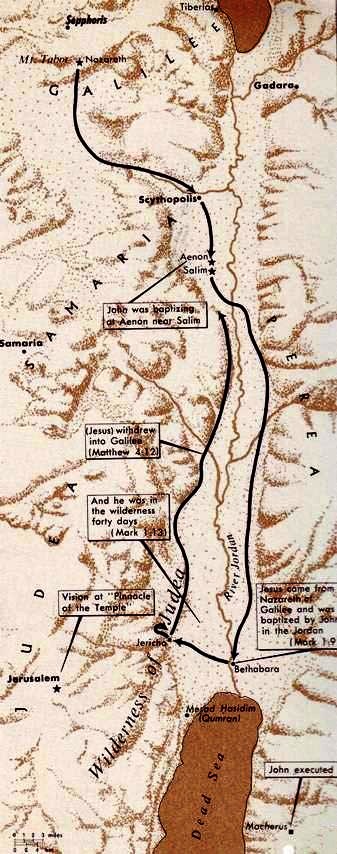

1. Nazareth, where Mary lives, is only a few miles from Sepphoris, the capital of Galilee (see top left of the map at right). It was much more sophisticated than little Nazareth, and there were Roman soldiers stationed there. Mary and the other inhabitants of Nazareth certainly came into contact with these soldiers at various times.

Sepphoris is in the north of Galilee

2. At around about the time that Jesus was conceived, much of Galilee was in open revolt against Roman rule. This revolt followed immediately after the death of Herod the Great in 4BCE. Sepphoris, only four miles from Nazareth, was the center of the revolt in Galilee. The royal palace there was attacked and looted (Josephus, Ant.17, 10.5/271-72). The whole area was a hotbed of seething resentment against the Roman occupation.

3. In the mopping up operations after the rebellion, the Roman general Gaius burned Sepphoris and sold its inhabitants into slavery. Remember that Sepphoris was less than four miles from Nazareth. Some of this violence and disorder must have been felt in Nazareth, only an hour’s walk away.

5. Is it too much of a stretch of the imagination to think that in this situation a young girl may have been raped by a soldier from nearby Sepphoris? Any Roman soldier stationed in the backblocks of Galilee would have been the dregs, socially speaking, of an army already noted for its brutality – a ‘kill first then let’s talk’ policy was what had built the Roman Empire.

6. Early Jewish writings (the Baraitha and Tosefta, written about 150-200AD) openly talk about Yeshu the Nazarene, who was the son of a Roman soldier called Pantera. ‘Yeshu’ is the original Semitic word for ‘Jesus’. Though it may of course be pure coincidence, a tombstone was also found of a ‘Tiberius Julius Abdes Pantera of Sidon, aged 62, a soldier of 40 years’ service, of the 1st cohort of archers’. Jesus, during his short career as a philosopher/teacher, makes an otherwise unexplained trip to Sidon, detouring quite out of his way to go there. (Mark 7.31) It seems a strange thing to do, unless he has some connection to the place.

So a Roman soldier as father of Mary’s unborn baby is a possibility. No more than a possibility, but at least that.

Mary visits her cousin Elizabeth, Giotto, Padua

File written by Adobe Photoshop? 5.0

The visit to Elizabeth

It’s at this stage of her pregnancy that Mary was sent away to stay with a respectable cousin, Elizabeth, probably a relative of her mother’s. It’s possibly done for her own safety.

The usual practise under such circumstances is to try to hush things up. A discreet curtain is pulled over the whole matter. After the birth of the child the young girl returns, with or without the baby.

Such a practice has existed in most societies, with everyone being tactful and pleasantly horrified – schadenfreude, as the Germans call it. People pretend the scandal never happened.

But this does not happen with Mary. Joseph seems to have a change of heart, and she returns to Nazareth some time before the birth.

Why did Joseph take responsibility?

At this point in the story, Joseph offers to marry her. As I see it, this is one of the central questions in the story of Mary.

Why does Joseph, who has been humiliated by Mary’s pregnancy, agree to marry her even though he knows he’s not the father of her baby? (Matthew’s gospel makes it clear that Joseph knows he is not the father.) What does he know that we don’t?

We get some clues from the same gospel.

This account of events around Jesus’ birth starts with a genealogy. By Jewish standards of the time, it is a strange genealogy. It includes the names of four women, a very unusual thing to do. Biblical genealogies usually only mention men’s names. So why is this one different?

The women mentioned are not the ones you’d usually boast about as being among your foremothers. Each of them has a story, which you can read by following the links.

But not only that. Each of them has a ‘past’.

- Tamar is the first. She was a determined Jewish woman who was refused her legal right to bear a child. She would not accept this injustice – the status of Jewish women was measured by their children, and without a child she is condemned to a bleak future. She dresses as a temple prostitute. Disguised this way (prostitutes at that time hid their faces behind a veil) she had sexual intercourse with her father-in-law, Judah, and conceived a child. When her pregnancy became obvious, she was sentenced by Judah, as head of the clan, to burn to death. Only when she was able to prove that he was the father was the sentence of death revoked. She bore twin sons, a clear sign that God was on her side. (Genesis 38)

- Rahab is the second in Matthew’s genealogy. She is a prostitute in Jericho. At considerable risk to herself, she helps Joshua, the leader of the Jewish people after Moses, in his efforts to capture Jericho. When Jericho is captured, the lives of her parents and family are spared by the rampaging soldiers. Joshua 2:1-21, 6:22-25)

- Ruth, the third woman, has one of the great love stories of the Bible – a biblical Mills and Boone.

The man Ruth wants, Boaz, cannot be brought to propose marriage, even though it is obvious he is in love with her. Boy meets girl, boy loves girl, boy will not propose. Ruth has to resort to some blatant sexual ploys to bring him into line, but she wins the day. And if you’re reading the story for yourself, you’ll understand things better if you know that ‘foot’ is a biblical euphemism for male genitals. (Book of Ruth 2-4)

The man Ruth wants, Boaz, cannot be brought to propose marriage, even though it is obvious he is in love with her. Boy meets girl, boy loves girl, boy will not propose. Ruth has to resort to some blatant sexual ploys to bring him into line, but she wins the day. And if you’re reading the story for yourself, you’ll understand things better if you know that ‘foot’ is a biblical euphemism for male genitals. (Book of Ruth 2-4) - Bathsheba is the fourth woman mentioned in the genealogy of Jesus. She is the wife of Uriah, but King David sees her and lusts after her. She may have been raped, or she may be complicit in the act,

but through her eventual marriage to David she becomes wife of one king and mother of the next, King Solomon. She is an extraordinary woman whose illicit pregnancy eventually benefits the whole of Israel. (2 Samuel 11:1-26, 12:15-25, 1 Kings 1:1-37, 2:10-25)

but through her eventual marriage to David she becomes wife of one king and mother of the next, King Solomon. She is an extraordinary woman whose illicit pregnancy eventually benefits the whole of Israel. (2 Samuel 11:1-26, 12:15-25, 1 Kings 1:1-37, 2:10-25)

For more on these women, see The Ancestors of Jesus of Nazareth

- Each one of the four women in Jesus’ genealogy had an irregular sex life. None were as respectable as you might hope.

- But each one, in Jewish thinking, formed an important part in God’s plan. In fact, each one is indispensable to the working of God’s plan for Israel.

- This is an important clue to Mary’s situation, and of course it shows the way that Matthew, when he came to write his gospel, presented Mary’s irregular pregnancy.

What sort of man was Joseph?

After the genealogy in Matthew’s gospel, we’re introduced to Joseph. He is presented as a man of principle who wants to do the right thing but isn’t quite sure what the right thing is.

He thinks of sending Mary away quietly, and in fact this is about the time when she makes a visit to her cousin Elizabeth, obviously a highly respected and respectable family member.

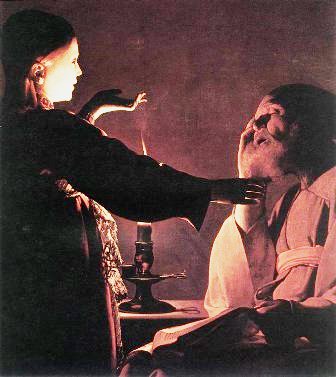

Joseph’s dream, George de la Tour

But then he seems to have what we in the modern world would call a psychological breakthrough.

We’re told an ‘angel’ appears to him in a ‘dream’.

What exactly is an ‘angel’? In this case, it seems to be an idea that comes so strongly into Joseph’s mind that it must be coming from somewhere else. Not only from somewhere else, but also from Someone else, that Someone being God. It is a conviction that settles on his mind, telling him he has to follow a particular course of action.

In modern words we’d say his subconscious was speaking to him. We don’t believe in dreams the way the ancient people did. They, unworried about their image, said it a different way: an angel spoke to them in a dream telling them something they had to do, and they were bound to obey because they had been told to do whatever it was, by God.

Why did Joseph marry her?

Very few men, if any, marry a pregnant girl just to be helpful. Joseph must have access to other information.

He must have known who the real father was.

Part of legal thinking at the time held that wrongdoing was the responsibility of the whole community, not just of the individual who committed the crime. The reasoning was that in a small, tight-knit community, people ought to be aware of wrongdoing, and take measures to stop it happening. If those measures were not taken, then the community was to some extent guilty of the crime.

We do much the same thing when we blame society for current social ills like drug-taking, petty theft, etc.

Icon of Joseph and the child Jesus

Perhaps Joseph knew that Mary had been wronged in some way, and felt a sense of outrage about what had happened. He tried to protect her and her child from unmerited censure. He had, after all, known her and her family since they were children. Maybe he knew she has been an innocent victim of something quite outside her control and as such should not be blamed.

Matthew emphasizes the fact that Joseph was well thought of in the community.

- Why else would a man like that, a just and respected man, be prepared to take on responsibility for another man’s child?

- Was he aware of exactly what had happened?

- Did he know who the real father was?

- Or was it just a shrewd guess?

We cannot know the answer for sure, but we can make an educated guess.

And an interesting little question: does anyone ever think about Joseph’s mother in all of this? Of what she thinks about her son’s decision to marry a girl already pregnant to someone else?

Knowing Jewish mothers, I’d be happy to bet she had an opinion on the matter.

In any case, the marriage ceremony went ahead. But everyone in the town of Nazareth, small as it was, knew that

- Mary became pregnant before the official marriage ceremony with her fiancé Joseph

- Joseph was not the father of the child and had to be persuaded to marry her

- Joseph ‘named’ the baby, calling him Jesus; by doing so, he recognized the child as his own, and accepted legal responsibility as father of this newborn child.

Where was Mary’s baby born?

Mary and Joseph at the birth of Jesus

We’ve all grown up with the idea that Mary has her baby in Bethlehem, with a star shining over the stable.

Well, maybe. And maybe not. Despite all the beautiful hymns written about the matter, despite the Christmas cribs, despite the legends, there was simply no good reason for Joseph and Mary to be in Bethlehem at that time.

- First, there was no census being taken then. The first census taken by the Romans was in 6AD, on the order of Quirinius, legate of Syria. Palestine came under his jurisdiction. (Josephus, Antiq. 18, 1.1, 6/1-11, 23-25). It was documented because it was a very unpopular census. People at the time knew its purpose was to gather tax more efficiently from them.

- Second, people registered for a census in the town where they normally lived. For Mary and Joseph, this was Nazareth, not Bethlehem. No one was required to go to a town of tribal origin.

- Third, a woman in advanced pregnancy would never have left her home village and her family, since this was far too dangerous for her and the baby. Jewish women give birth in their own houses.

Unfortunately, the idea of Jesus being born in Bethlehem is almost certainly an invention. It was meant to reinforce Jesus’ connection with kingship and the House of David. The writers of the gospels probably never meant it to be taken literally as a real historical fact. Its purpose was theological, not factual.

What was the birth like?

During the birth of her son, other women surrounded Mary (in Nazareth): a midwife, her relatives and friends, and female servants if there were any – in Mary’s case, there were probably no servants.

Mary would certainly have seen other women giving birth, so she knew what to expect and what to do.

Childbirth was commonplace, and not private.

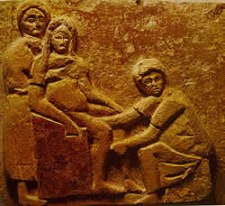

Ancient childbirth,

with birthing chair

In primitive times, women squatted over a hole hollowed out of the ground, standing on bricks or stones at either side of the hole. They gave birth in a squatting position, with the closest relatives and friends taking turns to support her under the arms.

But by Mary’s time there were special stool/chairs with a U-shaped hole in the seat and supports for the feet and back. See Childbirth in the ancient world

As soon as the baby was born it was washed and wrapped in long bands of cloth (swaddling bands), which held the limbs of the baby firmly, though not tightly.

These bands gave the baby a sense of security; we do much the same with modern babies when we wrap them firmly in a shawl. Swaddling bands were also thought to promote strong, straight bones as the baby grew.

What was Mary’s life in Nazareth like?

After the birth of her first child Mary’s life followed the familiar, comfortable pattern of a Jewish peasant woman.

The ideal Jewish woman was described in Proverbs 31:10-31. It was this ideal that Mary would have aimed for. You might like to compare it with the tasks expected of a modern woman.

A woman in biblical times was expected to:

- find a respected and well-to-do man to be her husband; Mary had already done this

- spin and weave cloth; this was a continuous activity for women in the ancient world, one that was never really over

- make and sell cloth and finished items of clothing

- organize suitable clothing for all members of the household, for winter and summer

- dress herself well

- keep herself physically and mentally strong and fit

- give religious instruction to her children

- work to produce crops, then assemble a varied diet for the members of her household

- administer the finances of the family and oversee the finances of the family business; this of course depended on her position in the family hierarchy – more was expected of a senior woman than a junior one

- invest any profits wisely

Village woman sifting grain

- perform charitable work and care for the poor

- organize and supervise the tasks of all those worked in her household, if she was in a position of authority

- oversee the emotional and physical well-being of all the members of the household

- be available at all times to anyone who needed her

The day was never long enough.

You will notice the list hardly mentions children. This is not because children were unimportant — quite the reverse. It was taken for granted that children were the central concern of a woman’s life, and did not need to be mentioned.

What did Mary do?

Mary performed all the small tasks of daily life, common to any woman in a farming community.

She washed clothes, probably in an open-air communal water-trough. The communal wash-troughs all over the Mediterranean world were famous for gossip and camaraderie.

She carted water from the single ancient spring that served everyone in Nazareth.

This well in Nazareth has probably been built and re-built many times; the well used by Mary of Nazareth is said to have been on this site

She prepared food for daily meals.

- Steaming bread cakes made from wheat or barley flour were a daily item.

- Popcorn, made by putting fresh grain on a metal plate over a fire, was popular.

- At certain times of the year the women were swamped with the task of preserving and drying crops like grapes, dates and figs.

- Olives were eaten fresh or pickled in salt water.

- There was a wide range of vegetables, eaten fresh, or dried and stored: beans, lentils and peas, onions and leeks, melons and cucumbers.

- These were made into spicy soups.

- Goat cheese and yogurt were common, eaten fresh because of the heat.

- Dried fish and eggs were sources of protein, with chicken, mutton and lamb for special occasions.

- The food may have been simple, but the taste was strong, seasoned with rock salt, vinegar, mint, dill and cummin.

The clothes of the day were plain in design, but they were made entirely by the women of each family —

- tending the goats and sheep who grow the wool,

- clipping the animals,

- spinning and carding the wool,

- weaving the cloth,

- shaping and sewing the clothes,

- mending them when they showed signs of wear…..

Each house was a thriving little production center.

As well, every Jewish woman, young and old, knew the small tasks involved in caring for the elderly, and for family members who were ill – sponging their face and hands, combing their hair, tidying the room.

The work may have been shared among all the women, but it was still heavy work, and Mary probably ate her food with a hearty appetite at the end of each day. Her life centered on her house, her village, and the land around it.

The inside rooms of her house tended to small and dark, so the courtyard and the roof were important work areas, since they had better light. Spinning and weaving, for example, could only be done with a good light. Food preparation also needed light.

Middle Eastern Village, 19th century photograph

The flat roof of her house could be used for sleeping, for working and for drying food or textiles. Rahab, the female ancestor mentioned in Jesus’ genealogy, hid Israelite spies under the heaps of drying flax stalks on the roof of her house. It was also a cool place to sleep in the hot weather.

Down in the courtyard was the mikveh, available for whoever needed it. This was where the cooking area was, with an open fire, an oven and an array of cooking utensils. There was a mortar and pestle for grinding small amounts of grain and a covered area where people sat while they worked or talked.

In a corner of the courtyard was the family toilet, emptied every day into a communal manure pit.

Did Mary have other children?

God’s first commandment, given to Noah in Genesis 9:1 was ‘Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth’, and Jews took this commandment very seriously indeed.

It’s hard to see why Mary wouldn’t have taken it seriously too. Jewish women were fertile and proud of it. They were glad to be able to produce life from within their own bodies. They saw a lack of children as a terrible misfortune.

A good Jewish woman – and Mary was certainly this – saw it as her duty to have a number of children, to carry out this commandment as best she could. A story in Mark’s gospel (3.31) talks about Jesus’ brothers and sisters – though in 1st century Palestine this could refer to cousins as well. Matthew’s is the earliest gospel, and probably the most historically accurate.

The idea of Mary being a virgin throughout her life came later, and was more about Jesus than about Mary. The Virgin Birth, described in Luke’s gospel, made Jesus unique, godly, comparable to the Greek and Roman divinities of the ancient world.

So yes, it’s possible that Mary had a number of children, hopefully a whole tribe of them, with Joseph as their father.

Jesus may have been simply the eldest of these children.

Meanwhile, what was Joseph doing?

As we’ve seen, the amount of work in Nazareth was not enough to keep a carpenter/builder employed full-time. Joseph had to move around seeking work. Fortunately there was a great deal of building going on in Palestine at that time. Herod the Great, who ruled Galilee when Jesus was born, was one of the great builders of the ancient world.

Even after Herod died, there was still work for a builder. The fashionable town of Sepphoris, near the village of Nazareth, had been burnt to the ground at about the time Jesus was born, but it’s an ill wind that blows no good. Herod Antipas, Herod the Great’s son, rebuilt it on a lavish scale, providing work for hundreds if not thousands of men in the building trade. Joseph must have been one of them.

One of the grand colonnaded streets in ancient Sepphoris

The new Sepphoris was a Greek-style city shimmering in the sunlight of Galilee. It had great open courtyards paved with cut stone, and a ‘we-mean-business’ type of fortress permanently garrisoned by Roman soldiers. There was a Greek-style theater that seated upwards of 4,000 people, a palace to cater for visits of Jewish royalty, colonnaded streets, an upper and a lower market place, government archives, and even a bank.

Joseph and Jesus were probably involved in rebuilding this city.

It’s odd to think that Joseph and Jesus were almost certainly on the payroll of Herod Antipas, that great villain of the New Testament!

Mary’s eldest son is a worry

Portrait of an older woman

So from his earliest years, Jesus had contact with two very different ways of life – traditional, conservative, rural life in Nazareth, and cosmopolitan, sophisticated, Greco-Roman Sepphoris. Judging by the gospels, he also seems to have had regular experience of hierarchical, ceremonious worship in Jerusalem.

He was a complicated young man, with a strong sense of worth and the confidence to believe that what he thinks is in fact true. His birth wa shadowed, and so he was not entirely accepted as one of the villagers in Nazareth.

Perhaps this was why he didn’t settle easily into an ordinary life. He had trouble fitting in. He was clever and restless. Mary watched him with all the anguish and love of a mother.

At some stage, he left home and became a wandering teacher and charismatic healer. Mary probably worried about him, and like any good Jewish mother she let her thoughts be known on the matter.

Did Mary understand her son Jesus?

That one is hard to answer. She was a normal Jewish peasant woman. She did not foresee the future. She may have known he had extraordinary ability, but she could not know he would be the founder of a breakaway sect of Judaism. As a conservative Jewess, she would probably have been deeply troubled to know that her son would later rebel against conservative Jewish authority.

One thing she did realize was that he was getting himself increasingly distrusted by powerful people. She decided she must do something, to try to save him from himself.

We don’t know what brought things to a head, but at one stage she and her other children went after him, to persuade him to return to Nazareth.

They had obviously heard that he was saying and doing things that offended and upset people, especially people in authority. He was getting himself into trouble. Possibly Joseph has recently died.

It would, she may have thought, be much better for everyone if he came home, married a nice girl, and took on the duties of an eldest son.

Jesus’ response to this was hostile, rude, confronting. In effect, he disowned his family and claimed the people he travelled with were his ‘real’ family.

The incident must have been a profound shock to her. I’m always rather disappointed the gospels don’t tell us what her comment on the matter was. Pungent, I imagine.

Jesus visited Nazareth. What went wrong?

Jesus rejected at Nazareth

The next we hear of Mary is during a visit that Jesus made to Nazareth. He was at first greeted warmly, as you would expect of a returning traveler.

But then things went sour. Just why they went so sour so quickly is not entirely clear, but it would seem the people of Nazareth did not treat Jesus with the respect he had now become accustomed to. He resented their skepticism.

Probably, the basis for this skepticism was Jesus’ illegitimacy.

How, after all, could a man born outside wedlock be respected or even taken seriously as a spiritual teacher and leader? These were people who took their lineage very seriously indeed.

Today, knowing what type of people your past relatives were doesn’t matter too much. We ‘judge people on their own merits’. Ancient people tended to look more critically at what sort of background you had, what your people were like. As the tree grows, so shall the branch…..

Events surrounding Jesus’ birth were murky. It was not so much that Mary had become pregnant before the final wedding ceremony, but that Joseph was not the father, as he should have been.

So people reasoned that his mother was not quite respectable, and her family had not produced a branch they could be proud of. Spiritual leaders and teachers had to come from the best stock, have impeccable backgrounds, if they were to be credible. Jesus did not.

Moreover, he was not a tactful man, and he rubbed people up the wrong way.

It’s interesting to speculate what the world would have been like if Jesus had done as his family asked, been tactful and cautious and stayed at home to run the family business.

But he wasn’t, and he didn’t. He stayed on the dangerous path he’d set out on, and became one of the greatest Jewish ethicists of all time.

As long as Jesus stayed in Galilee, he was reasonably safe. Herod Antipas ruled there, and he was a tolerant, rather lazy man. Despite what history has said about him, he only killed when he had to.

But Jesus felt impelled, for whatever reason, to go to Jerusalem at Passover time, and this wa a whole different ball game, and much more dangerous.

Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem

By this time, Jesus was a celebrated figure with a large following.

Something convinced him that now was the moment to confront the Temple authorities head on.

He made a very public, staged entry into Jerusalem, when there are large crowds of people there for the annual Passover celebration. He went to the Temple, that most hierarchical of institutions, with his egalitarian message.

Passover was the worst, or best, possible moment to make such an open challenge.

Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem

From Mary’s point of view, it must have seemed like madness. She was a pragmatic peasant, and she probably would have advised him not to seek out trouble, because it will find you soon enough.

At the same time, she loved this errant son of hers, enough to be there in Jerusalem when he made his move. Or she may simply have been there as one of the pilgrims. She and her family members seem to have made frequent pilgrimage journeys to Jerusalem.

Things had changed since his neighbors in Nazareth dismissed him. He had a large following now, of people from all over the country.

Did Mary expect her son to be the catalyst that would tip Israel into the messianic age?

It’s impossible to tell. Both of them had their fears, but Jesus certainly expected something momentous to happen.

Whether or not she shared that belief, we will never know.

The plan goes wrong

The authorities were on the alert; Jesus was swiftly arrested, tried and found guilty.

Pontius Pilate was Roman to the core, and not about to take chances with state security.

In the darkness, jostled by the crowds, Mary was probably only partly aware of what was going on. Whatever the events actually were – and there is much debate about what really happened – she knew her son was in deep trouble, arrested as a rebel against Roman authority and tried for blasphemy.

He was found guilty, and almost before she knew what was happening, she was standing on a hillside watching her eldest son being crucified.

Crucifixion – an horrific way to die

Crucifixion was designed not so much as revenge as a deterrent. A site close to a crowded highway was preferred, with the victim naked and in full view of everyone traveling past. To humiliate him, his genitals were not discreetly covered as they are on traditional crucifixes.

Head of Christ Crucified, Nicholas Ge

The crucifixion had three parts:

- a beating/whipping,

- a harrowing journey to the place of execution, and

- the nailing and lifting of the cross into place.

A notice on a piece of board, attached to the top of the wood, told the crime that had been committed.

The upright beam of the cross was already in place. Across it might be nailed a flat board, which could act as a sort of seat. The condemned criminal carried the cross section to the place of execution.

The person to be executed was nailed through the wrist rather than the hand, as a nail through the palm could tear through the flesh when the body weight bore down on it. It the person was nailed through the hand, ropes had to be tied round the upper arms to support the body weight.

The crossbeam, with the person hanging on it, was lifted into place with Y-shaped poles, and dropped into a mortise on the upright. The feet were then nailed to the upright.

The person died from a combination of asphyxiation and blood loss.

They could breathe as long as they held their body straight, but this meant putting the full weight of the body on the flesh torn by the nails in their hands and feet. If they eased this weight by letting their body sag forward, it was difficult to breathe.

The muscles of their arms, legs and thorax went into spasm, and they were unable to exhale properly. Their lungs filled with carbon dioxide, their breathing became a ghastly asthmatic wheeze, and they eventually died. This could take quite awhile, sometimes several days.

Jesus was luckier than some. The beating he took beforehand at the hands of the soldiers must have been especially severe. That, coupled with the loss of blood, sent his body into severe shock, and he had a relatively quick death.

The Romans meant brutal business, and they made capital punishment as fearsome as they could. Death by crucifixion, in a public place, was as humiliating and ghastly a death as was ever devised.

Mary at the crucifixion

Most parents would go under, seeing such a thing. Mary did not. She survived the unimaginable ordeal of watching this happen to her son.

Her mental toughness and innate strength were extraordinary. No doubt it was the worst moment of her life, but her endurance put the lie to all those simpering modern statues of Mary.

This was a woman as strong as an oak, with a peasant’s stoicism and endurance.

Mary buries her son Jesus

Mater Dolorosa – the Sorrowing Mother

She was there at his death, and she was there to bury him. It was the last act a loving mother could perform.

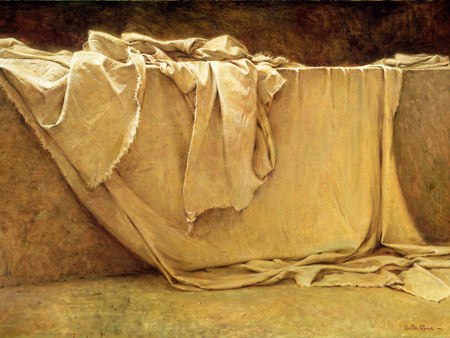

In 1st century Palestine it was a woman’s task to prepare the body of a family member for burial. The body was tenderly washed, and hair and nails cut. Then it was gently wiped with a mixture of spices, and wrapped in linen strips of various sizes and widths.

While this was happening, the women prayed, wept, and talked to the dead person – all the things we still do when we mourn. Afterwards, they would tell stories about the person, remembering him.

You will notice that a good many of the post-death stories about Jesus are told from the women’s point of view. This grew out of their ritual story-telling after his death.

Normally, the body was then carried to a tomb and laid on a long shelf carved into the stone. It could be wrapped in a shroud, but was otherwise uncovered.

Then the tomb was visited and watched for three days by family members.

On the third day after death, the body was examined. This was to make sure that the person was really dead, for accidental burial of someone still living could occur. On this third day, the women of the family treated the body with oils and perfumes.

This would have happened if Jesus had died back in Galilee.

But he was in Jerusalem, far from home, so the procedure was different. Temporary graves were provided for pilgrims or executed people who died in Jerusalem. Usually, their bodies stayed there until they decomposed, and then their bones were taken home for permanent burial.

Jesus was placed in a temporary grave, lent to his family by a sympathizer. His body was meant to stay there until it could be taken back to Nazareth. The bones would then be collected and stored in an ossuary, a ‘bone box’, with the large bones at the bottom and the smaller bones and skull placed on top.

This was the normal practice. But something else happened, something that ignited a fire rather than snuffed it out. The body of Jesus disappeared.

What happened to Jesus’ body?

Burial clothes in the empty tomb of Jesus of Nazareth

No-one is really sure what happened. Possibly the Roman authorities removed his body and disposed of it, hoping his followers would simply disperse.

They had soldiers guarding the tomb, and during the night they may have taken the body from the tomb and put it somewhere else – perhaps dumping it out in the desert somewhere. This way, they reasoned, there would be no more trouble.

But the followers of Jesus were utterly convinced that something much more mysterious had happened, something that involved God’s direct intervention. They were convinced that Jesus was about to usher in a Messianic age, and that this had in fact happened, even though their Messiah figure was dead.

Mary and early Christianity

At first disoriented by his death, which they obviously did not expect, the family and followers of Jesus began a fierce promotion of his ideas. He had a vision of a perfect society and how it could be achieved and they intended, come what may, to keep talking about it to whomever would listen.

Jesus’ ideas caught on and spread. They appealed especially to the lower classes and to disadvantaged people like women and slaves, because they promoted the idea, revolutionary at the time, that all people should be equal. Embryonic Christian communities began to form.

There were however a couple of problems that had to be solved.

- Not only had this extraordinary Jewish man been executed as a criminal.

- There was also talk about his birth, and

- the marital status of his mother at the time he was conceived.

The story of his death was transformed by presenting Jesus as a sacrificial offering who had given his life for humanity. This was a familiar idea to ancient peoples, since they came into frequent contact with the sacrifice of animals in temples. Jesus was just such a sacrifice, the Christian groups argued, but on a much higher plane.

His birth was transformed too, with some ingenuity. There was a long tradition in the Greek world and in other ancient religions of human women giving birth to great heroes. Greek mythology is full of such stories.

Ancient peoples imagined the sort of person who might result from the mating of a human woman of extraordinary beauty with some elemental energy force in nature – the power of the sea, perhaps. The child that would be born from such a mating would be quite different to an ordinary human. It would have extraordinary powers, being something less than the deity who was its father, but more than a human being.

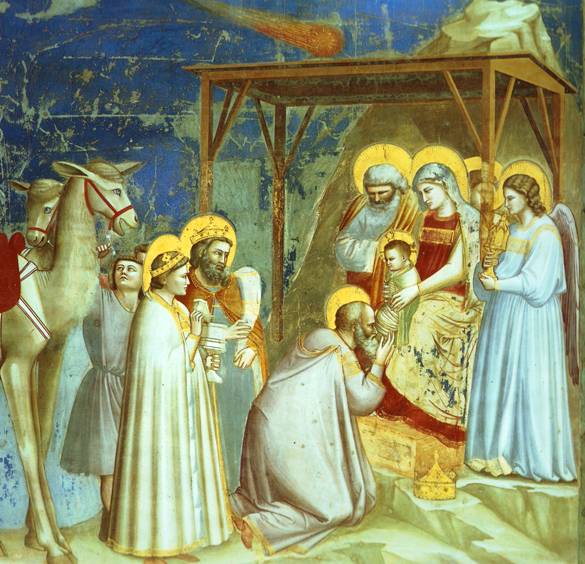

Giotto, the Wise Men visit the newborn Jesus

The idea gradually took shape that Jesus was just such a person. It explained the confusion surrounding his parentage, and lent status to his birth. It gave legitimacy not only to Jesus but also to his teachings and recorded actions.

Why is Mary, mother of Jesus, called ‘Virgin’?

This idea was backed up by something else that happened around then. The Old Testament, known to every Jewish man and woman, had originally been in Hebrew. But well before the time of Jesus, Hebrew had ceased to be the spoken language of Jews. In Palestine, Aramaic had taken its place. Large numbers of Jews lived outside Palestine, in countries fringing the Mediterranean.

These Jews spoke neither Hebrew nor Aramaic. They were more comfortable in the language of the country where they lived.

So in about 250BC the Jewish scriptures were translated into Greek, the language spoken by most Jews living throughout the Mediterranean. This meant that all Jews now had a common, Greek edition of their scriptures.

This new edition contained a significant mistranslation, in Isaiah 7.14. The Hebrew word ‘almah’, meaning ‘a girl of marriageable age’, was translated by the Greek word ‘parthenos’, which means a ‘virgin’, a woman with an intact hymen – two quite different things.

The fledgling Christian communities used both the original Hebrew version, and the Greek translation. One group uses the word ‘almah’, the other group uses the word ‘parthenos’. Confusion about the right meaning for the word arose.

When this passage in Isaiah was applied to Jesus, the confusion was magnified. Gradually, as the Jerusalem community lost its precedence, the Greek word became the ‘real’ word. With it came Mary’s translation from ‘a young girl of marriageable age’ to a ‘virgin’.

When this happened, the whole of Christianity shifted its axis.

What did Mary think of all this?

What Mary herself thought of it, if she was still alive, is lost to us. In early life she had been forthright, if we are to believe the scenes described in Mark 3:31, Luke 8:19 and Matthew 12:46), physically robust and apparently the leader of her family.

Perhaps the idea of a ‘miraculous’ birth only surfaced when she was dead. By that stage she was not there to pour ridicule on it, as any good Jewess would have done. After all, virginity was an alien idea to the family-oriented Jewish woman. It ignored the command of God, given to Noah, to go forth and multiply.

The idea was more popular with the groups of Christians for whom Luke’s gospel was written. In fact, the idea may have originated with him. Certainly it sat very well with Hellenised Jews, who were steeped in Greek culture, and familiar with all the Greek stories about gods and mortal women.

But as time went on the idea caught on for another reason. The ancient religions, in all their beauty and wisdom, were slowly disappearing. Their complex view of the human psyche and the forces of nature were going out of style. The gods and goddesses were dying.

Mary the mother of Jesus filled the void.

Mary, the Assumption of the Virgin, Murillo

Mary became the paradoxical Virgin Mother, the womb of creation.

She was everything to everyone, all the goddesses rolled into one.

- She was Hera, guardian and model for all families.

- She was Athena, valuing wisdom and civilization.

- She was Aphrodite, patroness of visual beauty, and the stimulus for countless lovely icons and paintings.

- She was Demeter, protector and nurturer of all creatures.

- She was Artemis, patron of childbirth and health.

- She was Persephone, protector in life after death and comfort to those who mourn the loss of loved ones.

What the early Christian communities were finding out was that people still yearned for a female image of God. It was not enough to have a male God with his male son Jesus. That might satisfy theologians, but ordinary people wanted someone who was female, with all the powers of the female – in particular, a mother figure, someone they could turn to when all else failed.

Mary of Nazareth, in her new incarnation, satisfied that hunger for a goddess. She acquired all the trappings of a goddess, her own churches, altars, devotions, miracles, art works. As time went on, she sometimes seemed more important than her son Jesus.

Mary as a sturdy peasant girl. Madonna, by Elliott, Cathedral of St Stephen, Brisbane

In each century, images of her reflected the current ideal woman. Sometimes that worked in women’s favor, sometimes not. Churches today are still prone to have images of Mary that reflect a 19th century idea of how a virtuous woman should be.

In them,

- Mary is sexless, flat-chested and thick-waisted.

- Her head is bowed forward, sweet and yielding.

- Her hands and arms are turned outwards, showing the soft underside of the wrist – a classic submission pose.

- She stands with her weight on one foot, off balance – unthreatening body language, all of it.

Not a very useful image for a modern woman.

The peasant woman in Galilee, with her dirty feet and stocky figure, had been entirely forgotten.

Over the centuries, another woman appeared in her place – benign, aloof and loving at once, gorgeously dressed, almost always with a single child in her arms.

Impossible to think of this calm goddess as she had been in life, the disgraced girl who found herself the mother of a religious radical who was executed as a criminal.

The Christian world had made Mary a goddess, shaping her image to suit its own needs.

The real woman was lost in the mists of time.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cornfeld G., (ed), The Historical Jesus, Macmillan Publishing, New York, 1982

McArthur, Harvey, In Search of the Historical Jesus, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1969

Powell, M A, The Jesus Debate, Lion Publishing, Oxford, 1998

Rousseau, John, Jesus and his World, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, 1995

Warner, Marina, Alone of All Her Sex, Quartet Books Ltd, London, 1978

Wilson, Ian, Jesus the Evidence, Harper & Row, San Francisco, 1984

Read about more fascinating women of the Old and New Testaments

Search Box

![]()

Bible Study Resource for Women in the Bible: the real Mary, Joseph and Jesus of Nazareth

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher