The Bible: history, memory, truth

Elizabeth Fletcher, Independent Scholars Association of Australia, 24.7.2010

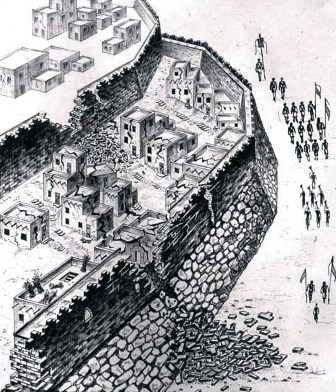

Reality (above) versus the idealised (below)

First, I want to state my position: I am looking at the Bible as a historian, not as a believer. I am a believer, but I want to put that aside so that I can look at the Bible from another perspective.

A believer searches for wisdom; a historian tries to reconstruct what happened at a particular moment in time. A historian’s task is to try to discern

- what is true

- what might be true

- what is probably not true.

A historian approaches the biblical stories as just that – stories – with a wealth of historical information embedded in them. Which is not, by any means, to say they are not based on true events.

A historian approaches the biblical stories as just that – stories – with a wealth of historical information embedded in them. Which is not, by any means, to say they are not based on true events.

But a historian does not take the stories as literal truth. In fact this stance, that the stories were about literal truth, would have puzzled the original story-tellers, who wrote on many levels, mostly symbolic and all of them profoundly sophisticated.

See Ancient History of the Middle East – Youtube video

Bible history: what really happened?

As a historian I might, for example, look at the story of Bathsheba. You may recall she was the beloved wife of King David and the mother of King Solomon. She was also the most powerful woman during the period of the early monarchy. After David’s death she occupied the most prestigious position a woman could hold, that of Queen Mother. She took part in court intrigues and influenced political events that gave the succession to her son Solomon.

That’s how she is usually introduced. This description emphasises the positives and plays down the negatives, which is something that instantly makes a historian suspicious.

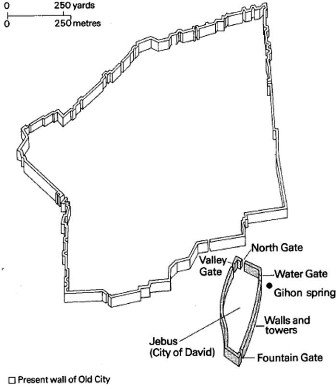

Jerusalem (Jebus) at the time of King David. David’s fortress was in the lower section; the upper section was only walled later on

In fact, Bathsheba was the young wife of a prominent army officer when King David first saw her. She lived in a house below the palace walls in Jerusalem, at that stage more a fortress than a city.

One late afternoon when she was having her ritual post-menstrual bath, which women often took in a screened area of the flat roof of the house, she was seen by David, who was standing, probably behind a lattice, on the open terrace of the palace apartments above.

‘Palace’ is perhaps the wrong word to describe the building where David lived. Judging from archaeological reconstructions of similar buildings in surrounding countries – nothing remains of David’s strong- house in Jerusalem – the building was probably more of a fortified long-house with side wings; the roof of these side wings supported a terrace of sorts.

Did Bathsheba know she was being watched? Your guess is as good as mine, but judging by later events I’d say yes. In later life she was an astute and manipulative woman, quite capable of shaping events to suit herself. At that moment, on the roof of her house, she was rolling the dice to see how they would fall.

Voyeuristic 19th century painters like to show her in a deliberately provocative pose, naked with arms raised above her head, and this image has entered our minds and continues to colour our ideas on the event. A historian has to disregard these distractions and look instead at what precedes the event, and what follows it. There are a few clues.

David, having seen her bathing, sends for her to come to the palace.

Does this mean she was, as feminist historians believe, taken there under duress? No. The Bible text uses just a few terse words to describe her reaction to his command: ‘and she went’. Whether she felt any scruples about doing so, we do not know. Certainly she knew the implications of going to the palace, and certainly her husband’s extended family/clan would have objected to her going in no uncertain terms.

At this point myth begins to change into history, because now in the story you have evidence of an event through the testimony of witnesses. As a historian, you are using the Bible as a primary source, and asking the sort of questions a historian asks:

- where does the story come from?

- what is the bias of the writer?

- what information is given, and what is left out?

- why is this piece of information given, and another piece left out?

As a biblical historian, I know that Bathsheba’s story originally came from the records of the royal court of the Davidic kings of Judah, but has been through many edits since it was first written. More to the point, I know that royal records, like modern newspapers, will only ever tell me two things:

- what they want me to know

- what they have to tell me because it is already common knowledge in the community at large. Pretty much in the same way that politicians work today – and Bathsheba is very much the politician.

So if I’m dissecting her story, I know that she was having her ritual post-menstrual bath. This means

- she has recently menstruated

- is not already pregnant

- but is approaching the peak time of conception in her monthly cycle.

In the next sentence, we are told that, following the visit to the palace, she has conceived and is pregnant. Because of the preceding information, we know the baby must be David’s. So the whole story of the roof-top bath has set the reader up for this conclusion.

At this stage, there is a jarring coda. This first-born baby dies. Bathsheba, installed in the palace harem, conceives again almost immediately.

The questions arises: why tell us something scandalous about King Solomon’s mother? Why tell us about a baby who dies and is therefore out of the picture, historically speaking?

The answer lies in the fact that Solomon will eventually seize the throne of Judah under very dubious circumstances indeed. He deposes and kills an older brother who not only has the right of primogeniture (though this is not a firmly established practice at the time), but has been acclaimed by ‘the people of the land’, which means by a confederation of tribal leaders – and this was a very powerful endorsement of any candidate for the throne. Until this date, it seems to have been the deciding factor in election to kingship.

So we can assume that Solomon’s right to the throne must have been hotly disputed at the time of his accession, and Bathsheba and the court faction supporting Solomon only won out over the older brother’s candidacy by using mercenary troops to suppress dissent. The older brother was executed on a trumped up charge, with testimony of treason supplied by, you guessed it, the Queen Mother Bathsheba – hardly a disinterested witness.

So why have the story of the rooftop bath and subsequent seduction? The historian, reading this story, surmises that one of the accusations made against Solomon at the time he seized the throne must have been that King David was not even his father.

The story of the rooftop bath and the summons to the palace rebut this. They support the idea that Bathsheba and David were an established couple even before the birth of Solomon, her second son. Therefore, the story says, Solomon must indeed be David’s son who had some right to succeed to the throne, even if a lot of killing has to be done to get him there.

Whether this was true or not is another story. Bathsheba’s court officials controlled the records. Their version of the story is the one that survived.

Memory: how do we recall an event?

Example 1: the story of Cain and Abel

The creation stories in Genesis 1-3 grew out of a society quite different to our own.

Nomad’s tents

There were two separate ways of life, co-existing with each other:

- nomadic life, where people travelled with their cattle, moving from pasture to pasture as the seasons changed and periods of drought and plenty occurred

- settled agriculture – farms and crops provided a relatively stable existence, and villages and towns gradually appeared.

Nomadic life was hard and precarious but relatively free and easy.

Agriculture was more secure but it meant back-breaking labour and problems such as

- individual land ownership

- hygiene and sanitation

- the stress of living with neighbours.

Reconstruction of the ancient town built by Akhnaton at Amarna, Egypt

People chose the system that best suited the climate and fertility of their land, but agriculture gradually won out over nomadic life, because it could support a larger population.

The struggle between these two ways of life is mirrored in the stories of the Garden of Eden, in Eve‘s choice of the apple, and particularly in the fight between Cain and Abel. Cain represents settled agriculture and village life, Abel stands for the nomadic way of life, which later settled societies looked back on through rose-coloured glasses.

In the ancient, early biblical world, both ways of life were locked in a struggle for dominance, and though the nomadic way of life lingered on in some places, it had been almost entirely replaced by agriculture. We do the same thing when we, an industrialised society, look back nostalgically at our past, at a world of farms, rather than factories.

The Bible remembers the struggle between the nomadic life and settled agriculture through a story where the different characters represent different ways of life. It is history remembered through a different medium, history embedded in a story.

Example 2: the story of Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife

At another level, people used memory of an event to lock an idea into their national consciousness.

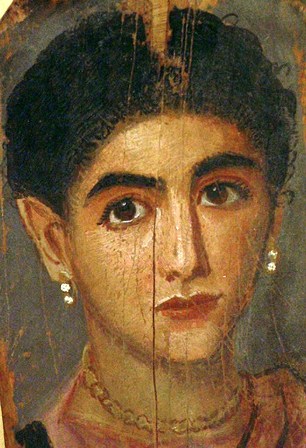

Portrait of an Egyptian woman, from a Fayum coffin portrait

Portrait of 1st-2nd century Egyptian woman, from a Fayum coffin portrait

An example of this is a story that unfolds in the household of a rich Egyptian, Potiphar, who owns many slaves. The time period for the story is uncertain, but it seems to be set during the Middle Kingdom, somewhere between 2030BC to 1640BC when, it could be argued, Egypt was at its zenith. It’s possible that ‘Potiphar’ may be linked to ‘Ptahwer’, an officer of Pharaoh Ahmenemhet III. But the name may also be linked with the word for ‘eunuch’ – the Bible is full of sly little jokes and innuendos like this, that were carefully excised during the Victorian era.

The Book of Ruth, for example, takes on a whole new dimension when you know that the words for ‘shoe/sandal’ and ‘foot’ were ancient euphemisms for male and female genitalia. But that’s another story…

Joseph and Potiphar’s wife live a period of economic prosperity. One of Potiphar’s slaves is the Hebrew Joseph, a man of unusual ability who has been placed in control of Potiphar’s large estate and household.

He is young and handsome, the Brad Pitt of ancient Egypt, and very clever as well.

Potiphar’s wife is a bored, rich Egyptian woman who, à la Mrs. Robinson, falls for this handsome young slave. She sees him, she wants him, and she tries to get him. She is unsuccessful and, chagrined, accuses him of rape. In the way that the story is told, she is a corrupt, unscrupulous person and he is a virtuous and vulnerable man whose life she ruins.

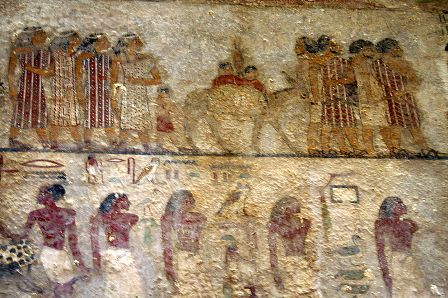

A group of travelling merchants, probably Hebrews, from the Egyptian tomb at Beni-Hassan

A group of travelling merchants, probably Hebrews, from an Egyptian tomb at Beni-Hassan

That’s on one level of the story. On another level, Potiphar’s wife and Joseph are code for Egypt and Israel, and the different ideals, different cultures, and different practices of the two countries.

The seductive nature of Egyptian society and culture always posed a danger to Israelite culture. Egypt’s sophistication was admired throughout the ancient world, and many people came under its influence. But the Israelites led by Moses eventually fled from it, just as, in this story, Joseph fled from the arms of an alluring Egyptian woman.

There were other things about Egypt that repelled the Israelites. For example, they did not like the land tenure laws of the Egyptians, where land was owned by a rich landlord who held it on behalf of Pharaoh. The Israelites in the early kingdom period believed that parcels of land had been allocated to each tribe, not given to any individual owner, and that land was held in trust by each tribal leader and his descendents. It could not be bought and sold like a normal commodity.

This is why Naboth refused to sell his land to King Ahab and his wonderful wife Jezebel. She was not a woman you could mess with. She solved the problem by organizing the swift judicial murder of Naboth.

Despite her ruthlessness I have a fondness for Jezebel, partly because she gets a raw deal from the biblical writers, and partly because of the unfairness of the way her name is associated with sexual immorality.

Ivory carving of the Woman at the Window, circa 8-9th century BC

Jezebel was not sexually immoral. If anything, she was fiercely loyal to her husband, who was King of the northern kingdom of Israel. After he was killed in battle and her two sons murdered, she is described in the last moments of her life as putting on make-up and ‘adorning her head’, probably with one of the heavy ritual wigs worn by royalty at that time. This is where the ‘painted Jezebel’ epitaph comes from. In all probability she was putting on the tradition make-up and clothing of a queen and priestess of Baal, as she prepared to die.

She went out in fine style, shouting insults at her killers and refusing to be afraid. Good for her.

The biblical writers hated her with a vengeance. She was foreign, powerful, and loyal to the fertility gods that the Yahwist priesthood tried, not entirely successfully, to suppress. They aligned her with the ‘Woman at the Window’, a famous image that appears in ancient Middle Eastern art, and was probably linked to worship of a goddess like Asherah or Athirat, a fierce goddess, mother of gods, ‘she who strides across the sea’.

The biblical writers were of course Yahwist priests, supporters of the Yahwist party. ‘Impartial’ is not a word you would use to describe them.

Search Box

![]()

Truth: whose truth? yours or mine?

Example 1: the Zealots of Masada

Now we turn to one of the key moments in the New Testament, when Pontius Pilate and Jesus confront each other at the trial of Jesus, and Pilate asks that seminal question: what is truth?

Jerusalem by this stage is a very different place to the fortified town it was in King David’s day. It is an imposing city with a religious area that according to the Bible account outshines the Acropolis in Athens.

Reconstruction of the Temple of Jerusalem

as it was at the time of Christ

Pilate was an educated Roman, and certainly aware that one of the central questions of philosophy is the nature of truth.

The trial scene in John’s gospel is an interesting confrontation between the two men, one a Galilean peasant with a brilliant grasp of the complexity of the human condition, the other a sophisticated Roman aristocrat well-versed in Greek learning.

Pilate gives us the question, but not the answer. What is truth? Is it your truth, your reality? Or mine? This is the eternal problem for the historian, and it continues to be asked in today’s world.

I’ve recently been researching the Zealots, who were core instigators of the Jewish Revolt in 1st century Palestine. This group was utterly dedicated to getting rid of the Roman presence in the Jewish state, and some of them ended up committing mass suicide at the fortress of Masada in southern Israel, killing every one of themselves rather than surrender to the Roman army.

It was probably a wise move. At best, if captured, they would have ended up as slaves, but even this was a long shot. By the time that Masada was taken, Jewish slaves were a glut on the market. No one was keen to have them. No-one is ever keen to have utterly committed rebels cooking their tea or farming their land, or even working in their mines. They are too much trouble. So the Roman soldiers would probably have slaughtered the Zealots on the spot anyway.

A short dagger similar to ones used by the Zealots

Before their highly dramatic deaths, the Zealots had been successful urban terrorists, and it is not surprising that the Romans hunted them down. The Zealots’ method was this: they used a small dagger easily concealed within the folds of their clothing. At festival time – there were four major festivals in ancient Jerusalem – they mingled with the dense crowds until they were close to their target, usually a Roman official or a fellow-Jew whom they considered to be a collaborator, then they jostled their way up against their target and stabbed him. In the ensuing confusion they were usually able to vanish into the crowd.

The parallels with modern-day terrorism are easy to see. The truth is that the murder of one official, like the deaths of 52 people in the London Tube bombings, was not threatening to the overall safety of the State. But the fear and paranoia it could generate was substantial, out of proportion to the numbers killed. It achieved its aim, causing panic among people who no longer felt safe in a public place.

The Zealots are revered in Israel today as liberators and freedom fighters. Masada has become almost a site of pilgrimage, a holy place. So my question is: were they freedom fighters or terrorists? And back to Pilate’s question, and the historian’s dilemma: what is truth?

Example 2: Joshua at Jericho

Taking a large step back in time, we go to the invasion of what was the land of Canaan, later Israel, by the Hebrew tribes when they came spilling out of Egypt.

Do you remember the film ‘The Ten Commandments’ with Charlton Heston as Moses? A rather pretty young actor called John Derek played Joshua.

This was total miscasting. The real Joshua was an experienced military commander who led some very tough people. Think of one of the hard-faced military commanders in present-day Israel and you’ll have it.

Joshua knew what his task was – to capture a foothold for the Hebrew people in Canaan – a land that was strange and hostile

strange because it was not Egypt, where they had come from

strange because its people, the Canaanites, were more sophisticated and better organized than the nomadic ex-slaves of the Hebrew tribes, and they did not welcome the newcomers.

Capturing Jericho was Joshua’s first great victory. But there is debate about how it actually happened.

Reconstruction of the moment the walls of Jericho collapsed

You’ll be familiar with the story of Hebrew priests circling the walls of Jericho, blowing trumpets until the walls of Jericho came tumbling down. Did it really happen?

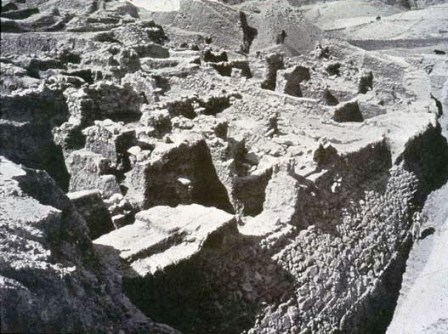

Archaeologists at Jericho have uncovered signs of a fierce fire and massive destruction – storage jars full of charred grain, fire-darkened bricks, burnt foundations of houses, that sort of thing.

So we can assume that Jericho was destroyed by invaders at roughly the time that Joshua lived, and was conquered and burnt at harvest time, matching the biblical account in Joshua Chapter 6.

But was it the Hebrews who did t his damage?

That’s more difficult to say. Up to this point they were nomadic wanderers, moving from place to place with their flocks, so they carried only light equipment, not objects that survive the centuries. In other words, there’s no tangible evidence of their presence at the scene.

What we do know is that they infiltrated the area over a period of time in about the 14th century BC, gradually taking possession of villages and towns.

Ordinarily they wouldn’t have had a snowflake’s chance in hell. The Canaanites were better equipped and organized, quite capable of repelling any attempt at a takeover.

Excavated walls of ancient Jericho. The human figure at far right shows the scale of the buildings.

But these were not ordinary times. There was a great multi-country migration going on at the time, with civil unrest and disorder everywhere. The Hebrews had only been able to flee Egypt because it was in chaos.

Pharaoh’s control had been drastically weakened in Egypt, the great tombs and temples were being looted, the army was embattled – so the Hebrew slaves seized their chance to escape.

What was happening in Egypt was also happening in Canaan. Jericho had once been a major city, but now it had fallen on hard times and could no longer defend itself. By the 14th and early 13th centuries BC, it was relatively small, an open settlement sheltering under once-great walls.

The Hebrew tribesmen were quick to take advantage. They seized what sites they could, including Jericho, then adapted to Canaanite culture – we know this, for example, because there is no break in the design of pottery and domestic articles during this period.

Did the walls of Jericho come tumbling down at the sound of Joshua’s horn, as described in the Bible? Again, hard to say.

In Joshua 2:1 he commands his soldiers to reconnoitre the city, and then later, as the priests sound their horns, the walls collapse. This collapse is backed up by archaeological evidence. The walls certainly did come tumbling down at about this time. There are collapsed stone and mud brick walls all over this level of the city. But from an archaeologist’s standpoint, it is impossible to tell whether this destruction was caused by invasion or earthquake. The truth is, it was probably both.

In any case, a literal reading of the story may not have been what the biblical writers intended. According to the Book of Joshua, the Hebrews were able to capture Jericho because they made a ‘great noise’ on their shofars, rams’ horns that were the traditional instruments of summons for the Israelite herdsmen.

A large number of shofars blown at the same time would make a very loud noise. But in Hebrew the ancient word for earthquake is ra’ash, literally a ‘great noise’. A great noise destroys the city of Jericho. The implied meaning of the original text is that the ‘great noise’ of Yahweh, an earthquake, destroyed the walls and helped Joshua capture Jericho. So a literal reading of the text, that Jericho was destroyed by the sound of the horns, rather misses the point.

To sum up: the Bible is a far more sophisticated and complex piece of writing than modern readers realize. It contains all the things we have been talking about today – history, memory and truth. Please don’t limit it to a literal reading of the words.

Search Box

![]()

Women in the Bible: a resource for Study Groups and Schools: The Bible as History

Bible history links

Whose version of the story are we getting?

Cain & Abel

Nomads versus farmers

Jesus and Pilate

Confrontation

at the trial

Joseph & Potiphar’s wife

Israel versus Egypt

Jezebel

A powerful woman

Famous Paintings

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher