Ancient Cities of the Bible

What were ancient cities like?

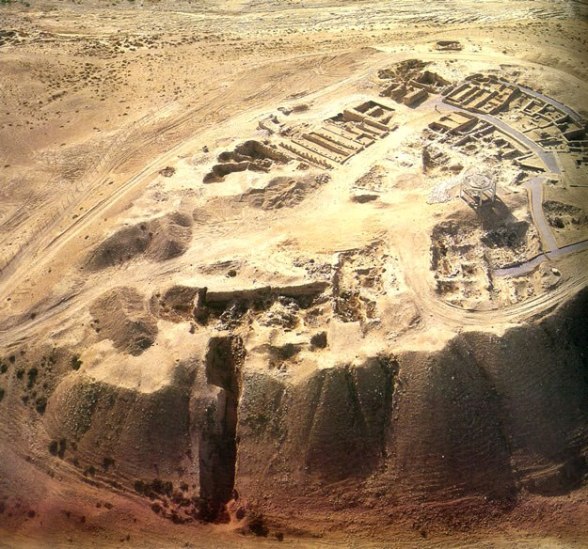

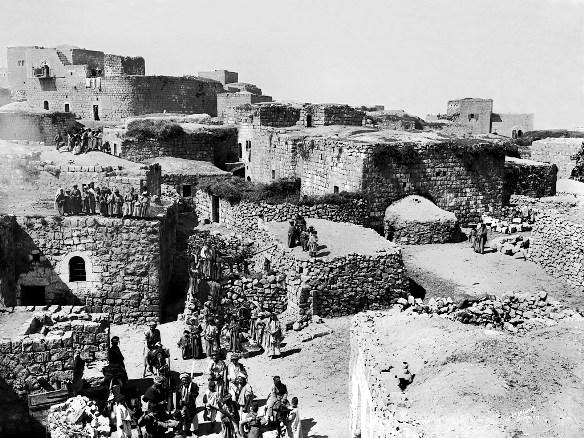

This is what ancient Bible cities look like now – the tel at Mamshit

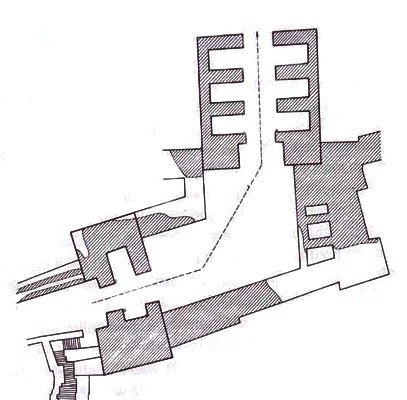

This is how an ancient city was set out.

Yes, it’s an aerial photograph of a medieval city in France. But it shows the way ancient cities were designed. There was a strong outer wall to protect all the important buildings: the palace, the main place of worship, and houses for all the people who acted as royal ‘back-up’: public servants, military personnel, craftsmen and traders. Cities in the ancient world used the same layout.

What did an ancient city look like?

It was on high ground, protected by a ring of walls, with a rampart leading up to the city gates. Inside the walls were houses of  varying shapes and sizes, but also large, important buildings that covered a substantial part of the walled area.

varying shapes and sizes, but also large, important buildings that covered a substantial part of the walled area.

Among these were the temple and the palace, often at the center of the settlement or in a prominent position.

All the houses were accessible via narrow alleys.

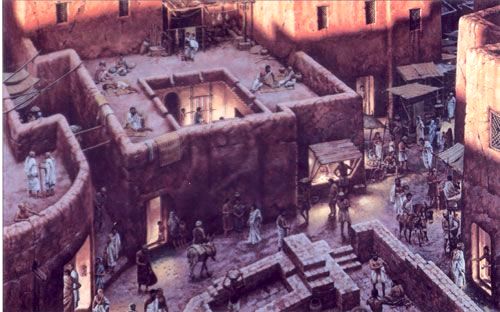

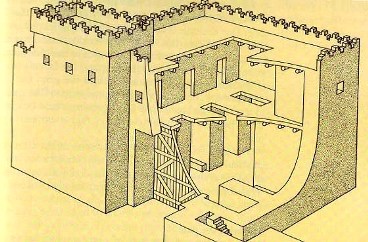

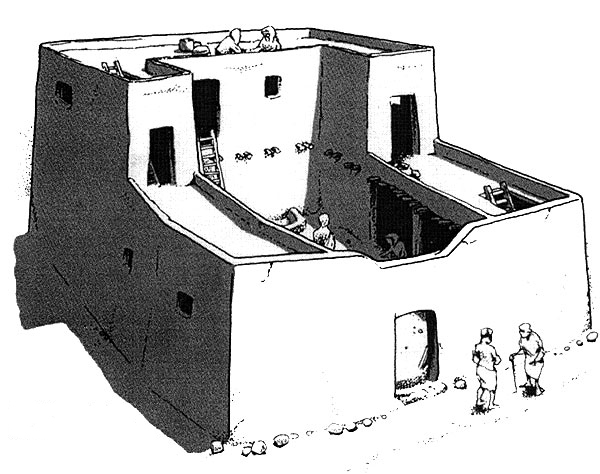

Reconstruction of houses in the ancient town of Uruk

What did a city need most? Water

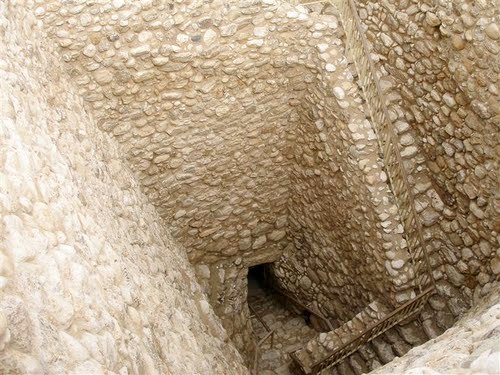

Before you built a city, you had to have a reliable water supply, protected inside plastered cisterns.

Before you built a city, you had to have a reliable water supply, protected inside plastered cisterns.

No water, no city. And the more water, the bigger city you could build.

As well, you had to protect your water supply. The installations at Megiddo make it clear that care was taken that water would still be available if the city was under siege or attack.

In Lachish and Jerusalem, the system of making underground tunnels to bring water into the citadel was further developed.

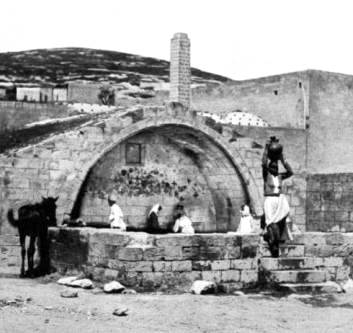

Entrance to a well built in the biblical era. What superb building skills these people had.

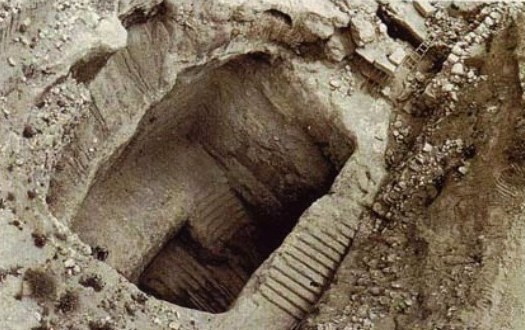

The water system at Hazor

What were ancient houses like?

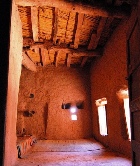

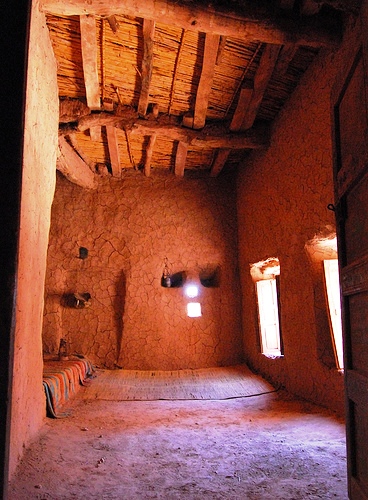

The earliest type of house was the wide-room house. Its basic design has changed very little (see the interior of a mudbrick house with small shuttered windows and a wooden roof, at right).

The earliest type of house was the wide-room house. Its basic design has changed very little (see the interior of a mudbrick house with small shuttered windows and a wooden roof, at right).

The floor was below ground level and you entered the room by two descending steps. The entrance from the street was in the shorter wall.

Rooms had benches running along the walls, and this might be the only furniture.

This basic design could easily be enlarged by the addition of extra rooms.

Fortifications – keep the enemy out!

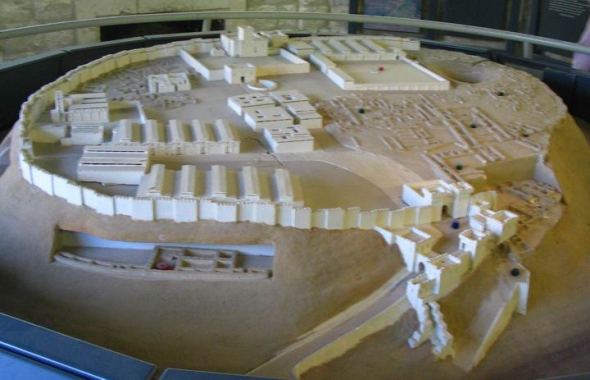

If a site had no natural defence (e. g. the slope of a hill), a thick bank of earth would be raised and the wall constructed on top. This is illustrated by the gateway of Megiddo (see below).

A model of the Megiddo tel; a high bank of rock and earth supports the entrance road and gates

An ancient tel and the city on its top would have looked something like this, minus of course the window-openings in the city wall, which are later additions

Before the monarchy, walls were made of unbaked bricks on a stone foundation. In the early days of the monarchy, casemate walls were constructed. These were made of two parallel walls, the outer one thicker than the inner, connected by a series of cross walls about 1.50-2 m. long which gave the whole system the appearance of a series of rooms. You can see this in the illustration below.

Casemate wall (double wall with central hollow space between the walls)

in the ancient city of Hazor

There were two ways these casemate walls could be used:

- They could be filled with earth in times of siege to make a strong defence against battering rams and similar siege engines.

- They also formed an inner ring road circling the town, for in several Palestinian cities houses were built up along it close to the inner wall, and the inside of the wall used for storage or housing (see the story of Rahab, the prostitute).

Later on, the casemate walls of a “royal city” like Samaria, built by Omri and Ahab of Israel (1 Kings 16:24), supported imposing superstructures, shops and a palace overlooking a paved courtyard.

Reconstructed Iron Age wall at the ancient city of Dan. Note the salient wall jutting out, and the size of the people standing before the wall. Soldiers defending the wall could easily target attackers.

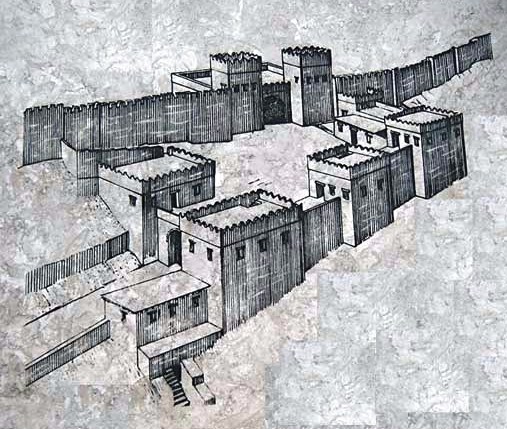

Types of fortification were improved during the monarchy and another very popular form of city wall developed, made up of a massive “broken line” of alternating recesses and salients (see the reconstructed Iron Age wall at Dan, right). This meant that attackers approaching the inside of the recess were exposed to the defenders standing on the salients on either side.

A typical Israelite wall was made of a mixture of hewn wrought and unhewn stones, the wrought stones being used for corners (cornerstones) and as headers and stretchers at fixed intervals; the space between them was filled by rough stones embedded in mortar.

This was a quick and cheap method of building.

Fortified Gates

Plan of the gate at Gezer

The gate of a city was

- the key to a city’s defence and

- potentially its weakest point.

Walls were broken for gateways only very reluctantly and then great care was given to their situation. Jerusalem had a number of gates, all mentioned by name in the Bible, but most Israelite cities had only two, one for wheeled traffic and the other, on the opposite side, for pedestrians only.

The road which led to the main gate was planned, wherever possible, with war as well as peace in mind. An army marched to the attack with the soldiers holding their weapons in their right hands and their shields in the left.

Why was this important to the city gate? Wherever possible a city gate was placed so that anyone coming up the road had the wall and its defenders on the vulnerable right-hand side.

Where, as in Megiddo, this was physically impossible, a second outer gate would be built to protect the entrance to the city (see the reconstruction of Megiddo’s gates below).

Above & below: a reconstruction of the gates at Megiddo, with floor plan showing the guardrooms on either side

The great door itself was guarded by two or more pairs of massive piers, forming the guardrooms between them.

Behind the first set of piers hung the door, with a huge vertical beam at each side, strengthened by strips of bronze. It moved on hinges fitted into hollowed-out stone door sockets on either side of the piers. The friction between the hinge and the socket (see dotted line in the image below) naturally wore out the stone so door sockets might be protected by bronze covers.

The sockets for city gates and the doors to other important buildings had to be replaced frequently. For this reason, many more worn-out door sockets than city gates have been unearthed in Israelite cities. Sometimes the socket stones were used in later buildings.

Gate-towers

The gateway was usually further protected by towers. These might be built over the doorway, as they were in Megiddo, or jutting out from it as in Hazor.

A ramp or stairway led up to the tower from the foot of the hill, or the bottom of the earth foundation on which it stood. The top sometimes had an outwork on it.

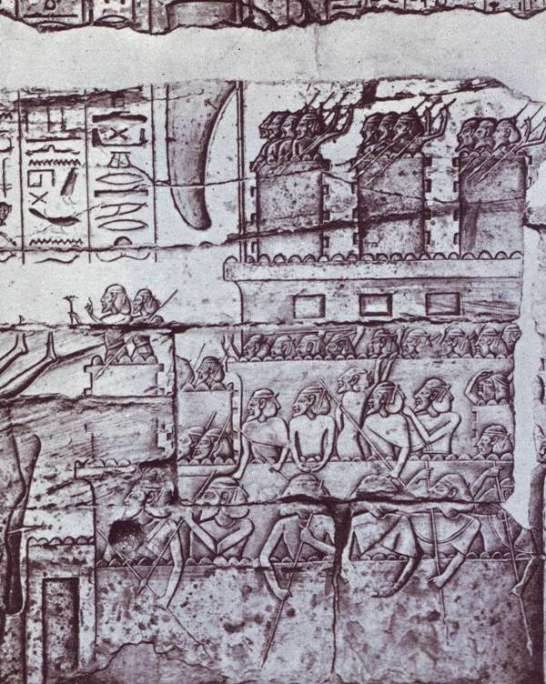

This wall relief of Ramses III attacking a Syrian town shows towers with wooden or stone transoms

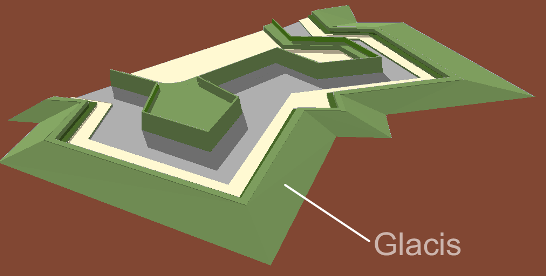

Many cities also had the added protection of an artificial slope or glacis with a ditch at the bottom – for example at Tel Sheikh Ahmed-el-Areyny (Gath) -see below.

Town-Planning

When we visualise a town, we see it with streets. This was not always so. In the earliest Israelite cities (Iron Age 1, 12th to mid-10th century BC) streets were almost unknown. Although Canaanite cities had streets and sewers, these disappeared.

Instead the city became a haphazard grouping of family units, ‘beit-ab’ or patriarchal houses.

Photograph of a 19th century Arab village with flat-roofed stone buildings and small windows similar to villages in Bible times

What were houses like in ancient times?

- Each house was a collection of rooms built around a central courtyard which would be used for all household tasks such as preparing and cooking food.

-

Reconstruction of a village courtyard

Around it, on the ground, floor, were workshops and storerooms containing, for instance, the great jars in which oil and grain were stored,

- while in the upper storey the family slept, four to six to a room, in winter.

- In summer, they slept on the cool, flat roofs.

Why did people build houses like this?

Because Israel had a shortage of long straight timbers. Standing timber such as pine and cypress was mostly used up in the spate of house-building during Iron Age I.

At that time, people gave up the nomadic life in favour of a settled life – so they built village and towns. Timber became scarce. Rich men like King David and his son Solomon imported timber, but the average person could not afford to do this.

Rooms were plastered and medium sized. A house would serve an entire family, from grandparents down to grandchildren. From the limited number of rooms in each dwelling it seems likely that they housed between one and two dozen people.

- One of the rooms on the ground floor was usually reserved for livestock and

- provisions were often stored in the living rooms.

Artist’s impression of a typical village house, with flat roof and central courtyard

A laneway connected the ‘big house’ and its dependent smaller ones, while each group was separated from the next by an alley. The only means of communication through the town was along these alleys or, more probably, through the courtyards. Privacy was more or less unheard of.

The lay-out of walled cities of the period followed a similar pattern. Inside, and a little distance from the walls was the ring road with houses, the gap between them and the wall being used as storage silos. The centre of the city was a closely-built maze of cramped alleys and dwellings.

‘Town’ replaces ‘settlement’

As long as the family and clan remained the central units of Hebrew society, haphazard town planning was appropriate.

But during the 12th, 11th and 10th centuries BC, tribal bonds weakened and were replaced by a central government. This gave cities a new status. They now featured public buildings and narrow streets.

Water Supply and Sewage

People in cities got their water from two sources:

- rain water stored in hollowed-out tanks under the houses and

- public wells within the city limits, from which water was collected in pitchers and jars.

Fountain of the Virgin, Nazareth

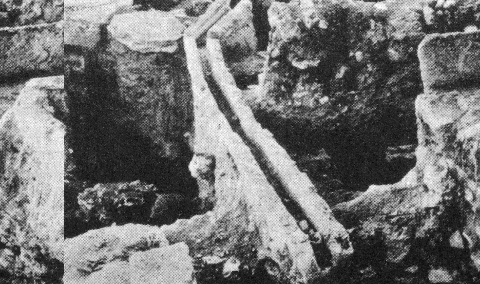

And what about sewage? We know there were combined bath and toilet rooms, mainly in the better class houses, from clay and stone sewers and pipes found in the foundations of Canaanite and Israelite cities (see below).

The sanitary facilities, bath-tubs and squatting oriental style toilets must have looked much like the remains of the bathroom in the palace of Lachish (8th century BC) – see image below.

- A drain passed through the bottom of the wall

- A water-closet fitted against it on the other side (see parallel stones, centre)

- A large tub would be used for cold water, the small one for hot.

- After a bath, the water could be run off through clay pipes into a drain or cesspool.

- The toilet was flushed from a ewer of water and emptied directly into the sewer.

- Sewers and pipes (see below) would be cleaned at intervals.

Archaeological evidence of drain and sewage channels in Lachish. Some modern archaeologists state that sewage, including human faeces, was simply hurled into the street and left there. To test this nonsense, try leaving household rubbish and faeces at the entrance of your own house for a week. People in the ancient world were not idiots. Every small village had a manure pit at its edge.

See the Youtube video on the history of Toilets, especially what instructions the Bible gave about sewage – Jewish people were scrupulously clean.

The City Gate

The social and economic life of the city centred around the gate. In peacetime, this was much more than the entrance to the city. People met there, did deals, heard news.

- There or close nearby was the market where outsiders could bring their merchandise to sell and could buy provisions.

- There the citizens came to take part in buying and selling, and to meet and gossip.

- There the city’s prostitutes did business – see the story of Tamar & Judah.

Gateway to the city of Megiddo

Rich and Poor

The growth and increasing power of a commercial class created a hierarchy of rich and poor. We know this from reading the Book of Amos – who criticised the tensions between the classes.

The 8th century BC level of Tirzah (Tel Farah) shows a group of excellent private houses with a courtyard flanked on three sides by rooms.  This is separated by a long, straight wall from a quarter in which smaller houses are closely huddled together. The rich did not want close contact with the poor.

This is separated by a long, straight wall from a quarter in which smaller houses are closely huddled together. The rich did not want close contact with the poor.

Most people lived by working in the fields around the town. Many peasants also lived outside the city walls, scurrying within them for protection in times of danger.

Storehouses

Ancient grain silo with stairs, Megiddo

Storehouses were often cut out of the soft rock on which the city stood.

Their upper part was shaped like a beehive. Their dimensions varied. The best preserved ones range from 4 to 11 metres in diameter, 3.75 to 7 metres deep, with capacities from 40 to 450 cubic metres. They were usually built on stone foundations, with a brick floor.

Very often the storehouse was part of the defences of the town, serving the needs of the local garrison.

One of the best examples is that discovered in Megiddo with two flights of steps, one used for people and loads going up, the other down.

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher