The Capitoline Hill in ancient Rome. Eventually, the ancient ‘high places’ evolved into a much more elaborate form of architecture

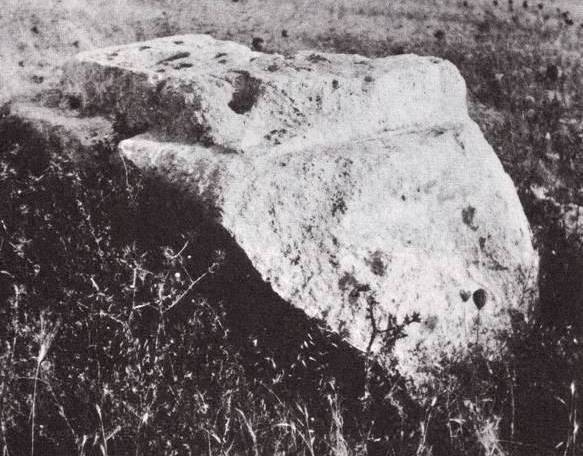

A ‘horned’ altar

Answer: because these ‘high places’, built at the top of a high hill or mountain, were part of the hated fertility cult of the Canaanites – hated by the priests of Yahweh, that is, not by the ordinary people, who hung on tenaciously to worship of the ‘old’ gods.

After all, the people of the Bible were farmers, familiar with Canaanite beliefs about weather and the cycle of the seasons. They were not about to abandon the old gods, who had looked after them, they believed, for millennia.

They already worshipped many gods. Now they simply added Yahweh to the list. That was fair enough. But abandon the old gods? No. An altar to Yahweh would be erected beside a hallowed stele (matzebah) and sacred tree or wooden pillar (asherah).

Monolithic stone altar in Malta

What were these ‘high places’?

The “high place“ was a country sanctuary, not a temple. They were not elaborate centres like the Israelite sanctuary at Shiloh or the Temple at Jerusalem. Marked by a tree or a group of trees, they were used for seasonal offerings and sacrifices in the countryside, and perhaps for ceremonies connected with clan or tribal memories of revered ancestors.

There was a long tradition of ‘high places’. Solomon built a ‘high place’ on a mountain, and they also existed near certain towns, in valleys and in ravines: ‘he sacrificed . . . on the high places and on the hills and under every green tree’ (II Kings I6:4).

What did a ‘high place’ look like?

Sit-shamsi found in Susa. This may be what a simple ‘high place’ looked like.

They were always raised above eye level, so that one looked upwards to them. Whether or not they were on an actual height, the “high place” itself was in the form of a mound, either a natural outcropping of rock or a man-made cairn or pile of stones.

Sometimes the high place contained ‘hammanim‘ or incense altars, used during worship.

Greenstone cylinder seal from Mesopotamia, with clay imprint of the seal.

The stylized tree in the center may be connected to the sacred tree or asherah.

To the Israelites, certain places were holy ground because God had shown His Presence there. The shrine of Bethel, for example, had been sanctified by God’s appearance to Abraham and Jacob. Jeroboam established a ‘beth-bamôth‘ there, literally, a ‘temple of the high places’, with altars and other cultic objects.

Reconstruction of a ‘high place’. Courtesy of www.bible.com

The tide turns against ‘high places’

Apparently ‘high places’ were not condemned at first in Israelite religion.

- Samuel (1Samuel 9:12 ff) and

- Solomon (1 Kings 3:3-4) sacrificed on a ‘high place’ (beth-bamôth) and

- the sanctuaries were visited up to the end of the monarchy and the reform of Josiah (II Kings 23).

But then Jerusalem became the center of worship, and the battle began. High places were condemned without exception and ‘bamoth‘ became synonymous with pagan sanctuaries and practices.

How do we know this? The chroniclers of the books of Kings, zealous for a religious revival, repeat over and over at the beginning of the reign of different kings of Israel and Judah, with the exception of the reformers, Hezekiah (527-698 BC) and Josiah (636-609 BC),

‘and he did not do what was right in the eyes of the Lord his God . . . and he sacrificed and burned incense on the high places . . .’

We don’t know exactly what ceremonies were held by Canaanite and Phoenician worshippers. The Bible assumes they are already well-known to its readers. But we can guess at them by looking at archaeological finds in Phoenicia, Carthage, Cyprus, Sardinia, Spain and Southern France.

Archaeological evidence of High Places

The problem is, of course, that the shrines were deliberately smashed by the prophets and the followers of Yahweh. Added to this, the centuries of took their toll. Stone makes a good building material. Why not use this large block of stone, once an altar, as a quarry for later buildings?

But there are still places that provide evidence: beth-bamoth, cairns and matzeboth dating back for a millenium before the Israelite conquest.

Here are some outstanding examples of ‘high places’ of the 3rd and 2nd millenium BC:

Pre-Israelite:

One of the oldest Canaanite high places known in the days preceding the Patriarchal period is the Megiddo cairn (see below). It was reconstructed some time in the Early Bronze Period (about 2500 BC) and remained in use until the 19th century BC.

Later, it became a kind of fossil, for another temple was constructed right next to it, following a quite different concept architecturally and therefore, most likely, religiously.

Megiddo ‘high place’ or bamah

The builders of the new temple constructed walls around the older bamah and it may be that in this way they expressed their veneration for the by-then ancient place of worship. It is possible they held ceremonies there, perhaps connected with ancestor worship.

The shrine at Hazor

The 13th century BC shrine at Hazor was probably destroyed during the fiery Israelite conquest of the city. It had a series of mazeboth, most of them plain; one shows, in relief, hands upraised as if in adoration, and above them the symbol of the moon. Not far from the row of stele was found the statue of a sitting person holding a cup in his hand. A number of cult objects have been found with these: a statue of a lion, a mask, and others.

The bamah in Nahariyah (see below) which stands beside a small shrine dating from the l8th century BC is about 6 metres in diameter.

Female figurines found at Nahariyah

The large monolithic altar (below) at Tsor‘ah, Samson’s home town, was apparently connected with a high place.

Large monolithic altar at Tsor‘ah, Samson’s home town

Sit-shamsi: Many scholars are inclined to regard the small 12th century BC model of the Sit-shamsi (see top of this page under ‘what did a high place look like?) found in Susa as a typical fully equipped bamah, with

- two altars at the sides of the model;

- the figures of a priest and a worshipper of the shrine’s divinity engaged in a purificatory act;

- two stele to their right;

- various cultic objects;

- troughs for dry offerings and libations and

- tree trunks, possibly asherahs.

The High Place of Gibeon

Both I Kings (3:3-5) and II Chronicles (1:3 ff) record the sacrifice which Solomon made at the ‘great high place of Gibeon’. The site is believed to be the village of Nebi-Samuel, the highest ridge visible west of the road leading to Jerusalem from the plain. There is an ancient tradition that Samuel was buried there, which may explain the name of the place.

Samaritan shrines

Better evidence for the ceremonies of the high place may have been preserved in the Passover celebration of the Samaritans at Nablus (see photograph below). There, the shrine is a rectangular enclosure of rough stones, trenches and hearths, quite simply fixed in the ground, very much like the Israelite sanctuaries that have been discovered. This may be a relic of the rites practised at the ancient high places.

Samaritan Passover, High Priest with scroll

Search Box

![]()

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher