Popular & sacred music in the Bible

Music was part of people’s lives from the very beginning. Hardly had God finished Creation when Jubal invented music. At the same time his brothers, Jabal and Tubal-Cain, introduced cattle-raising and metal-working, Genesis 4:21.

Music was part of people’s lives from the very beginning. Hardly had God finished Creation when Jubal invented music. At the same time his brothers, Jabal and Tubal-Cain, introduced cattle-raising and metal-working, Genesis 4:21.

The world was a busy place.

So Jubal was ‘the ancestor of all those who play the lyre and pipe’ – hence, the patron of all musicians.

(See Musical Instruments for pictures).

What was music for?

Music was not just for pleasure. It had an important place

- in prayers – both personal and public

- in work, providing a rhythmic beat for working in unison

- in important individual and national events.

Music in the Temple

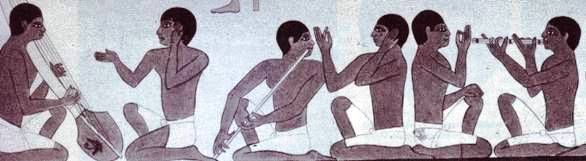

Above: Egyptian temple school for musicians, detail from a wall painting

The Jerusalem Temple would have had a similar school in the Temple precincts

In the early days, women predominated as ritual dancers and singers. They are prominent in the stories of Miriam (Exodus 15:20-21) or the women who welcomed David after his defeat of Goliath (l Samuel 18:6-7). Later, however, the Temple cult was restricted to men.

Bronze cymbals, Phoenician, excavated at Megiddo

Chronicles gives a full description of the musical activities of the Levites when it describes the purification of the Temple at the time of Hezekiah: ‘And he stationed the Levites in the house of the Lord with cymbals, harps and lyres’ (2 Chronicles 29:25).

See the Phoenician cymbals of the 10th century BC excavated at Megiddo at right, or the reconstructed Sumerian lyre of silver (below right).

‘And when the burnt offering began, the song of the Lord began also, and the trumpets, accompanied by the instruments of David, king of Israel. The whole assembly worshipped, and the singers sang and the trumpeters sounded… And Hezekiah the king and the princes commanded the Levites to sing praises to the Lord with the words of David and Asaph the seer, and they sang praises with gladness, and they bowed down and worshipped.’ (2 Chronicles 29:26-30).

Reconstructed Sumerian silver lyre, 2600BC

In the time of the First Temple built by Solomon, religious music was not restricted to the priestly class (the Levites). lt was part of the non-priestly cult as well.

The singers during this period may have been professionals, but they were not Levites.

Only after the return from Exile did Temple music become the exclusive domain of the Levites and the descendants of Heman (Nehemiah 12:27, 45 ff).

‘and the Levites with lyres and harps and cymbals and trumpets and innumerable other instruments…’

(See Musical Instruments for pictures).

Above: a court musician with lyre (centre), from an engraving on an ivory plaque excavated at the ancient city of Megiddo

Popular music

The mellifluous flute (ugéb, illustrated by the Roman relief from the 2-3rd century AC) or oboe (halil), lyre (kinnor) and drum (toph) were used to accompany songs at work and at festivals. During the monarchy, however, foreign influences and the development of urban life destroyed the earlier pastoral simplicity.

The mellifluous flute (ugéb, illustrated by the Roman relief from the 2-3rd century AC) or oboe (halil), lyre (kinnor) and drum (toph) were used to accompany songs at work and at festivals. During the monarchy, however, foreign influences and the development of urban life destroyed the earlier pastoral simplicity.

The splendours of orchestral sound and sophisticated court and urban dance music were introduced partly under Egyptian influence. The flute and lyre were replaced by more powerful wind and stringed instruments.

The first mention of professional musicians occurs in ll Samuel 19:35, when Barzilai regrets that age prevents him from enjoying ‘the voices of singing men and singing women’ at David’s court.

ln the 8th century BC, Sennacherib carried off male and female musicians from Jerusalem as part of the spoils of war, while Psalm 137:1-3 bears witness to the Babylonian demand for “songs of Zion”.

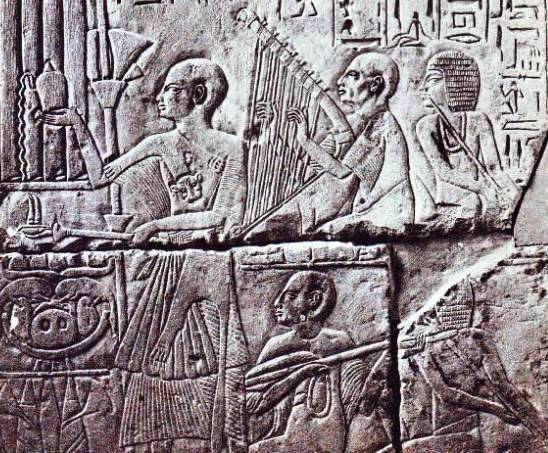

Captive musicians stolen by Sennacherib as part of the spoils of war

Music as the accompaniment to a life of luxury and leisure earned the condemnation of the prophets.

- Amos (6:4-5) mocks those who lie on beds with ivory ornaments and strum on their harps.

- lsaiah (5:11) foretold the doom of those whose only occupation was to ‘run after strong drink’ with ‘lyre and harp, timbrel and flute’ to entertain them.

Captive musicians stolen by Sennacherib as part of the spoils of war

Popular Secular Music

Popular secular music was a different matter: the Song of Songs is evidence of this. The songs of the vintners and the wine-pressers are also referred to in Isaiah’s lament for Moab (16:10).

Weddings were naturally rich musical occasions. The Song of Songs probably contains many of these songs and they were intended to be sung:

- Song 2:8 is a serenade in the springtime

- 7:12 was sung at the harvesting of fruits

- 4:4 or 5:10 is a sword dance

- 5:12-16 was sung at weddings to the accompaniment of musical instruments.

Even as early as Jacob’s flight from Aram (Genesis 31 :26, 27) Laban reproached him, ‘Why did you flee secretly, and cheat me, and did not tell me, so that l might have sent you away with mirth and songs, with tambourine and lyre?’

Music might be exhilerating, but it could also be soothing. David’s playing soothed King Saul when he was troubled by an ‘evil spirit’ (1 Samuel 16:23). The powerful emotional and psychological effect of music is acknowledged in ancient literature (e.g. the Orphic myths), and this is echoed in the story of the young David and King Saul.

Remains of the gold plated lyre excavated in the tombs of Ur by Sir Leonard Woolley. These would have been used in the royal court, as a similar lyre or harp was used when David played for King Saul.

The Sound of the Shofar

The sound of the shofar (made from a ram’s horn) was familiar at all periods of lsrael‘s history, summoning the people to solemn assembly, its blast claiming attention for announcements, proclamation of holidays and public events, coronations and of course calls to war and alarms.

Shofar, photograph by Roie Galitz

Trumpets were made of metal. ln the tabernacle or Temple worship, they were presumed to attract God’s attention.

Music for God’s Holy War

The ‘War Manual’ of the Dead Sea Scrolls is a nostalgic reconstruction of the epic deeds of the past. When the trumpet has sounded for God’s final Holy War, the members of the sect gird themselves for battle. Their army is organized according to the rules for the priestly war camp in the desert (Numbers 2:1-34) but the Scroll also owes a certain debt to a military manual composed during King Herod’s reign.

More important than the tactics prescribed, an atmosphere of religious exaltation pervades the camp, heightened by the sound of shofars and trumpets, reminiscent of battle scenes in Israel’s past:

‘Blown by levites and priests they sound. For calling to arms: a blast on the trumpets of assembly; a quavering blast for drawing the line of battle; a subdued note for advance to the enemy line; blasts on the six trumpets for preparing to slaughter; the priests are to blow upon the trumpets a sharp insistent sound to direct the wings of the battle; and all the people shall silence their war cries, while the priests keep blowing the trumpets for carnage….and the priests shall blow for them on the trumpets of pursuit.“ (War Scroll Vll:8-IX-9).

Battle scene: Gideon against the Midianites

The priests would signal withdrawal in moments of reverse, or would blow encouragement to the warriors. then urge them

‘to take up positions in their assigned places. Then the priests shall sound a second blast on the trumpets . . . everyone shall raise his hand with his weapons in it and the priests shall blow on the trumpets the signal for carnage and all the people with ram‘s horns shall sound a blast and the infantry shall start to launch an attack . . ‘ War Scroll XVI:11-XVll:5).

The Sound of Israelite Music

lt is much easier to discover, from archaeology and descriptions, what Israelite musical instruments looked like, than how they sounded.

Nevertheless, musical research has been able to get some idea of the rhythm, notation and acoustic qualities of Old Testament music, especially liturgical music from the time of the Second Temple.

For instance, certain musical patterns have been provisionally distinguished that later developed into traditional Church modes, e.g. Gregorian chant. Archaeological evidence for this is supported by the remarkable similarity between early ecclesiastical chants and the tunes intoned by remote Jewish communities (e.g. in the Yemen) who had never come into contact with Christianity.

The remnants of liturgical and popular music have been preserved in the chants and songs of the Jewish communities of Yemen, Mesopotamia, Persia, Syria and North Africa, where Jews lived in seclusion for more than thirteen hundred years.

The traditional antiphonal singing used in many of the Psalms (e.g. 13, 20, 38, 69, 89) was long retained in the synagogue, but when the mediaeval ‘hazan‘ wanted to impress his congregation, he began to embellish the traditional melodies. Signs or ‘accents’ were instituted to help the singers remember their variations and these were to have an influence on the beginnings of Western musical notation.

The book of Psalms, many of which were used in the Temple liturgy both before and after the Exile, gives some indication of the musical style in which the individual psalms were recited or chanted.

Unfortunately the terms used, whether referring to musical instruments or the type of psalm, have proved almost impossible to understand. Even the Septuagint translators were defeated by most of them.

This shows that the headings were already archaic and incomprehensible by the 2nd century BC – even though they are later than the Psalms which must be older still.

The words which appear at the head of the psalms apparently defined their nature, e.g. Mizmor, Shir (some- times Mizmor-Shir or Shir-Mizmor), Miktam, Maskil, Shir hama‘aloth (possibly, Pilgrim‘s Song, Song of a Returning Exile, or of a singer standing on the Temple stairs).

Higgayon (resounding music) and Shiggayon (wild or tumultuous music) may also belong to this group, although some authorities think the Words refer to musical instruments used for accompanying the singers.

Scholars are no nearer agreement on the meaning of Gittit, Minim (although it is now usually agreed that ‘minim‘ was not a single object, but meant a group of related instruments), Neginot, Nehilot (perhaps wind instruments), Alamot, Sheminith. Possible meanings of these obsolete terms are still being sought.

The general view is that some of them at least were not instruments, but melodies or styles of singing.

Reproduction of an Egyptian harp

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher