The Catacombs of Rome

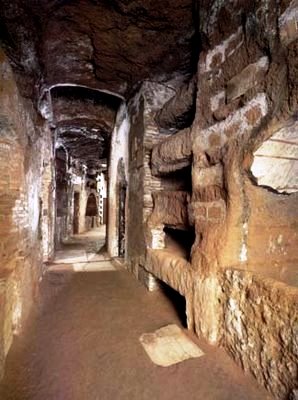

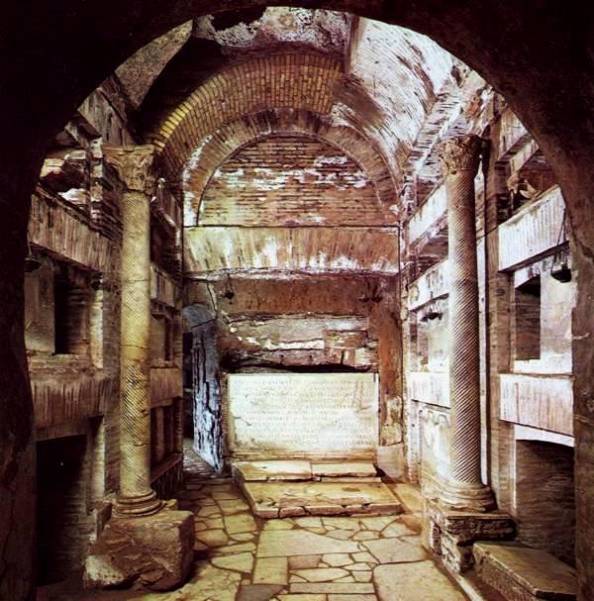

Well-lit corridor in the

Catacomb of St Priscilla

If you’ve ever been in a catacomb when the lights are off, you’ll get a foretaste of death. The darkness is total, overwhelming.

At right is a well-lit corridor in the Catacomb of St Priscilla. Nice and safe, and these days probably crowded with tourists. It was not always so.

Catacombs were ancient underground cemeteries with narrow winding tunnels normally about 8ft. high. The home of the dead. Not for the early Christians to hide in, as some movies suggest – everyone at the time knew they were there.

Why have catacombs?

They were used by the early Christian and Jewish communities for burial of the dead – early Christians rejected the custom of cremation, because they believed that bodies would one day rise from the dead.

At first the catacombs were used for funerals and then for memorial services, but later they became centers of devotion and pilgrimage.

Then, when relics became popular, they were greedily stripped of their contents.

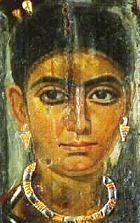

A richly dressed woman with arms raised in prayer, from the Giordani Catacomb in Rome. Usually the paintings in catacombs show scenes from the Bible; this is an exception. The detail in this face suggests she was a real woman known to the artist.

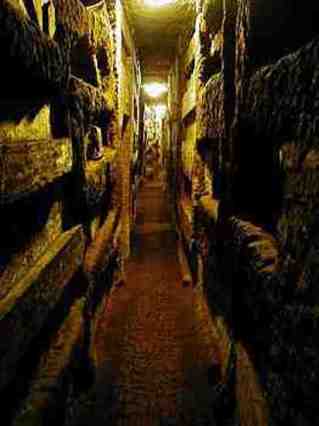

Catacomb of St Callixtus: A long gallery with loculi (cavities) on each side

Catacomb of St Priscilla, Rome. Horizontal burial loculi (cavities). A body was placed in each loculus and then a slab of stone was placed over the entry. The stone showed words or images to identify the person in the tomb.

Catacomb of St Callixtus; Tomb of the Five Saints. In fact, the mural shows six praying figures in a garden: ‘paradeisos’ is the Greek word for ‘garden’. Beside each figure is a name: Dionysia, Nemesius, Procopius, Eliodora, Zoe and Arcadia.

The catacombs were not only for Christians. This lavish tomb in the Catacomb of Via Latina has images of Hercules bringing heroic Alcestis back from Hades to her husband Admetus, for whom she had sacrificed her life – a story about love between husband and wife.

Christians and catacombs

The Christians of Rome were for the most part ordinary people. They lived in densely populated neighborhoods in the suburbs, near the places that offered the chance of good trade in supplies for the capital, or along the banks of the Tiber, or near industries like the transport services on the Appian Way.

Strangely enough, soldiers in the army seem to have been ready to listen to Christian teachings, and there were also many Christians among entertainment workers – in the circuses, amphiteatres, theatres, and naumachias dedicated to the public spectacles which were so important in Roman life.

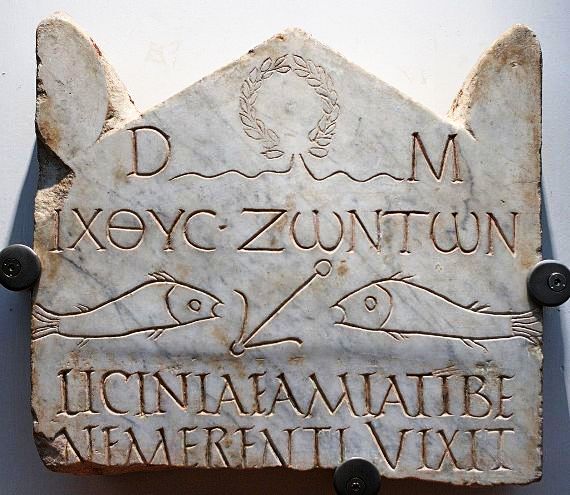

Funerary stele with the inscription ΙΧΘΥC ΖΩΝΤΩΝ (“fish of the living”), early 3rd century, National Roman Museum

Many more came from the great number of slaves who worked in Rome – from the imperial palace and the rich patrician residences to the city at large, where they made up the swarms of public servants employed in construction work, in the maintenance of aqueducts, road and drainage systems, and in fire-fighting and street cleaning.

See Slaves in the ancient world of the Bible for case studies of three slaves who appear in the Old and New Testaments.

A Roman coin showing the head of Domitilla the Elder, grandmother of Flavia Domitilla

But there were also rich and powerful figures among the Christians of Rome. By the end of the first century even the niece of the Emperor Domitian, Flavia Domitilla, had been sentenced to exile as a Christian and had ended her life on the island of Ponza with a ‘longum martyrium’ as St Jerome says. The Roman coin at right shows the head of Domitilla the Elder, grandmother of Flavia Domitilla.

After all, who but the wealthy could provide the economic means for organizing the Christian community? Believers gathered in their homes

- for the performance of eucharistic and baptismal rites

- to receive religious instruction

- to organize help for the needy.

During the 3rd century a certain number of these rich homes became established centers of Christianity, much like modern parishes today.

This wall painting of Christ is perhaps the first to show Jesus as a bearded man. It is from the late fourth or early fifth century AD. , from the Catacomb of Commodilla, and the tomb belonged to Leo, an employee of the ‘annona’, a revenue and food supplies administration center

Catacomb of Sts Marcellinus and Peter. Daniel in the Lion’s Den

2nd century fresco of Mary and the Child Jesus, said to be the oldest Christian image of the Madonna. Catacomb of St Priscilla, Rome (see also below)

Moses brings water from the rock, Catacomb of Sts. Marcellinus and Peter. This was originally the cemetery for the Emperor’s guards, but it later held the bodies of the many Christians martyred during Diocletian’s persecution

An underground cemetery

Because of the enormous population, residential Roman architecture developed upwards rather than outwards.

The limits of the city walls forbad urban sprawl. Buildings in Rome, unlike the ones in Pompeii and other cities, were up to four or five stories high.

A still from the film Quo Vadis, with St Peter preaching to the early Christians in Rome

So, in a sense, were the cemeteries. They were not built underground out of a desire for safety from persecution, which is a romantic fantasy shown in the movie ‘Quo Vadis’ where Christians use the catacombs as hiding places.

In fact, it would have been impossible to live in them for any length of time.

The ancients willingly made use of underground land when it could be easily and safely excavated. The soft tufa of Latium was ideal for a vast network of subterranean tunnels for waterworks, of chambers and galleries for graves, and even of recreation areas concealed in places called ‘cryptoporticus’ beneath summer villas.

The Christians and Jews of Rome simply used underground cemeteries to solve a problem which the large number of community members, and the choice of burial rather than cremation, had made increasingly difficult in a city where space was at a premium.

Without too much trouble, the multi-levelled network of catacomb galleries could be brought to a height of five meters. The chambers offered room for thousands of tombs along the walls and in the ground.

Catacomb of Pamphilus – the entrance. Unlike others, the tombs on the second level of this catacomb were found intact, decorated with ampullae, lamps, gilded glass and statuettes (see below)

Catacomb of Pamphilus. A bone statue mounted on one of the loculi/cavities. It must have been a personal object, to show who was buried there – this tomb did not have a written text identifying the deceased, and many of the poorer tombs had signs like this instead of text.

Crypt of the Popes in the Catacomb of St Callixtus. This contained the tombs of nine Popes who reigned between 230 and 283AD, and three African bishops who died during a journey to Rome

Burying the dead

Each corpse was wrapped in a sheet before being placed in the tomb, which often contained two or more members of the same family.

The name of the deceased was painted or sculpted on the brick or marble slab serving as its door, together with other information, usually the day and month of death. Small terracotta lamps and vases for perfume were often placed above the tomb, like the lights and flowers in cemeteries today.

Rectangular burial niches

in the Catacomb of St Priscilla, Rome

The sombre galleries lit by the dancing lamp flames must have made an impressive sight. See at right the rectangular burial niches in the Catacomb of St Priscilla, Rome.

The simplest niches were the loculi, rectangular cavities dug one above the other in the tufa walls.

A richer type of tomb was the arcosolium, a cell for the dead hollowed out of the tufa and often plastered and frescoed, with a horizontal slab for a lid over the grave, surmounted by an arch.

Arcosolia are most often found in cubicula, small rooms constituting family or corporation vaults. They are sometimes illuminated by pit-like openings in the vaulting like a skylight, which originally allowed for the removal of earth during the excavations.

The catacombs were used as cemeteries until the early fifth century. They became enormous underground cities, especially after the cult of the martyrs began, since ordinary people wanted to be buried closer to the sacred tombs as a near guarantee of salvation.

Coemeterium Maius, often called the Catacomb of St Agnes. The mural above shows a richly dressed woman, her hands raised in prayer. In front of her is a child. The painting is usually said to be an early Madonna and Child, but some scholars think it may be an image of the tomb’s occupant with her child. In other paintings from this period the Madonna was shown as a full-length figure, seated, with the baby in her lap, and there were nearly always figures around her, either people at prayer or Old Testament figures.

This mural from the Catacomb of Priscilla has been called a Madonna and Child, but there is some dispute. This catacomb has many scenes relating to persecution – Daniel in the Lion’s Den, the story of Susanna and the Elders, and a phoenix dying in the flames. They may suggest that the owner of the tomb was living through a period of persecution in the early Christian church.

Catacomb of Sts Marcellinus and Peter.

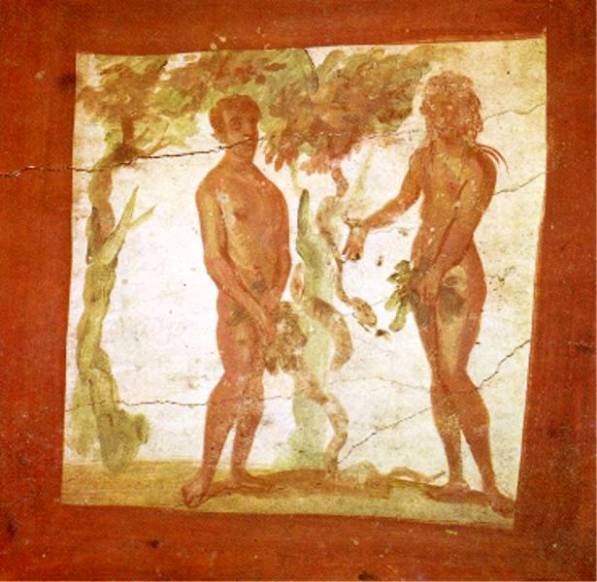

Catacomb of Sts Marcellinus and Peter. Adam, Eve and the Serpent

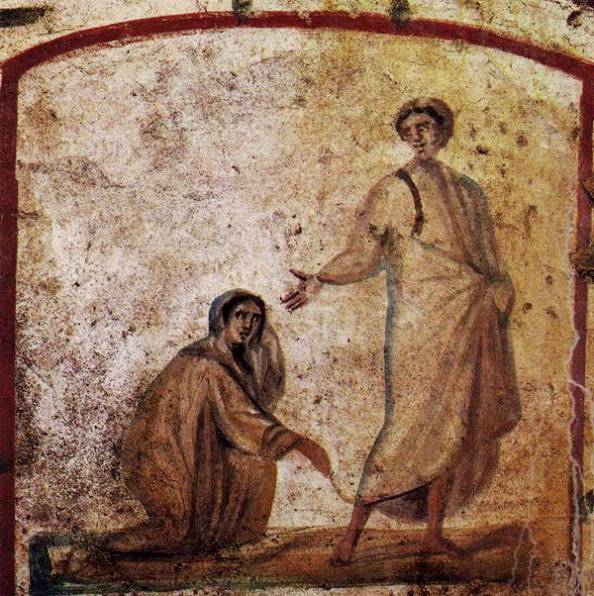

Catacomb of Sts Marcellinus and Peter. The mural shows Christ and the woman who menstruated for twelve years. It was one of three biblical scenes, all involving women: the Samaritan woman at the well, the healing of the crippled woman, and this one. In the vault above is an image of a woman at prayer. It was undoubtedly a woman’s tomb.

Saints, relics and pilgrims

When burials in catacombs came to an end, they became holy places. Immense numbers of pilgrims thronged to Rome from every part of Europe.

In spite of the wars against

- the Goths in the sixth century,

- the Longobard raids of the seventh and

- the growing insecurity and poverty of the Roman countryside

the martyrs’ sanctuaries were still regularly restored and embellished by the popes.

The Itinerari, guides for pilgrims written in the seventh and eighth centuries, show that devotion to them was still alive at that period. Nearly all of them were restored again in Pope Hadrian’s time.

But during the first decades of the ninth century the catacombs were looted for the relics they contained, which were transferred (perhaps for safety) from the original tombs to churches within the city walls.

Each and every catacomb was doomed to extinction, for the cult of the martyrs had been the only reason for their maintenance. When the relics disappeared, upkeep stopped.

The entrances to that dark underground world vanished beneath subsidence of the earth and an overgrowth of vegetation. Except for a few galleries, the catacombs remained unknown until the sixteenth century, when Antonio Bosio, “the Christopher Columbus of subterranean Rome” (!) began uncovering them.

Search Box

![]()

Catacombs links

____________

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher