What was Crucifixion?

Bible Study Resource

-

Crucifixion was a cruel form of execution for slaves and rebels. The condemned man was nailed or tied to a wooden frame, then left to die.

Crucifixion was a cruel form of execution for slaves and rebels. The condemned man was nailed or tied to a wooden frame, then left to die. - Crucifixion originated in Assyria, was used by Alexander the Great, then by the Romans.

- It lasted from about 600BC until abolished by the Emperor Constantine in 337AD.

- The crucifixion of Jesus is described in Matthew 27, Mark 15, Luke 23, and John 19.

The Cross: psychological warfare

The Persians probably invented crucifixion, then it was copied by the Greeks and Romans – who perfected this horrifying way of killing a criminal.

Photograph of the original ankle bone of a crucified man excavated at Giv’at ha-Mivtar, with a reconstruction of the bones

Originally the ‘cross’ was simply a stake that impaled the head of someone already dead – as happened in medieval times, when the heads of executed men and women were place on pikes at city gates or on battlement walls.

It was meant to terrify all those who witnessed it, and humiliate and torment the person condemned to die.

The Assyrians (see below right) were past masters of psychological warfare. They impaled captives to mock and terrify their enemies. The heads or bodies held aloft on spikes were intended as a public display, a humiliation of the enemy – see the wall carving from the palace at Nimrud (impaled captives are in upper left of picture at right).

In the Roman Empire, crucifixion was not normally used for citizens or free men, but reserved for people lower down the social ladder. Thus it became known as the ‘slave’s punishment’.

- Those higher up the social ladder, like St Paul, could demand a quick death by decapitation, which was considered more humane.

- Herod Antipas had John the Baptist beheaded, possibly because he admired or feared him.

Giv’at Ha-mivtar

Assyrians besieging a city. Notice the captives impaled on the city walls (upper left corner). This is probably how crucifixion began.

How do we know about crucifixion? Mostly from written sources like the gospels. But there is some archaeological evidence.

Bodies of captives (see right) or executed criminals were usually dumped as rubbish, to be eaten by scavenging dogs.

But in some cases, as with the death of Jesus, the body was retrieved by grieving relatives and friends and given a decent burial.

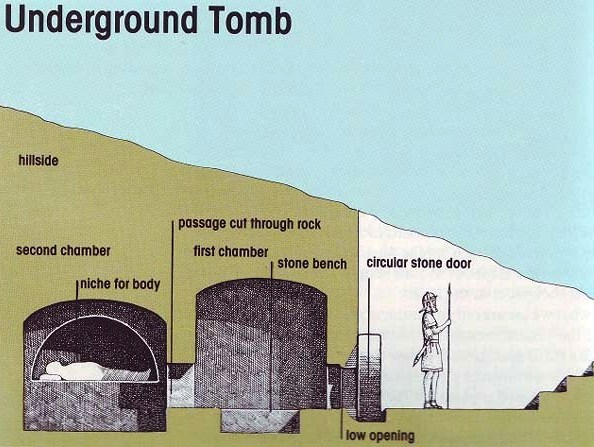

In 1968, the remains of one such man was discovered in a burial cave at Giv’at ha-Mivtar, northeast of Jerusalem. This cave contained five ossuaries or bone boxes (see Ancient Tombs for more information).

Photograph of the ankle bone of a man found at Giv’at ha Mivtar; the original nail is still lodged firmly in the bone of the crucified man

In one of the ossuaries were the bones of a young man who had died in his mid-twenties, crucified at about the same time as Jesus. A 4.5inch (11.4 cm) nail was still lodged in the heel bone of the man – apparently the people who buried him had been unable to pull it out.

There was even a small wedge of wood remaining between the heel bone and the head of the nail, which had been put there by some Roman soldier to hold the nail and his foot firmly in place.

According to the ossuary box inscription, his name was ‘Yehochanan’, which in English is ‘John’.

Both his leg bones had been smashed, something that was done to hasten the death of the crucified man – the gospels describing Jesus’ death emphasise that this did not happen to him, since he died quickly.

Torturing the victim

After a prisoner was arrested, he was held in a cell then brought before a court which decided what to do with him. If he was found guilty of the charges and condemned to die by crucifixion, he was often flogged beforehand.

Flogging involved stripping the prisoner and tying his hands to an upright post. A soldier stepped forward with the flagrum in his hand. This was a whip with a short wooden handle and leather thongs with small pieces of metal attached to the end of each thong.

The whip fell repeatedly on the condemned man’s head, shoulders and body.

Reconstruction of the whipping of Jesus, from the movie ‘Passion of the Christ’

The metal pieces on the flagrum first bruised, then cut into the skin and subcutaneous tissues, producing first an oozing of blood from the capillaries and veins of the skin, and finally spurting arterial bleeding from vessels in the underlying muscles.

Finally the skin of the back would be gaping open and the entire area would become an unrecognizable mass of torn, bleeding tissue.

This flogging was meant to punish, terrify and weaken the condemned man, and hasten death.

The severity of the beating matched the severity of the man’s crime. The Roman soldiers would have seen Jesus as a rebel and a terrorist, possibly one of the hated Sicarii. They would have used every sort of brutality and humiliation on him in the night after his trial – and the Romans soldiers sent to Judea were already bottom-of-the-barrel scum.

What they did to Jesus, and to any others like him, does not bear thinking about.

Crucifixion

When it was time to go to the place of execution, a heavy beam of wood, the crossbeam, was placed across the man’s shoulders, probably attached there by leather straps to prevent the weakened man from dropping it.

The route taken by the procession of soldiers and condemned man was along a crowded street, so that his suffering was evident to as many people as possible – crucifixion was used as a deterrent to other citizens who might be tempted to commit the crime for which the condemned man was being punished.

At the place of execution, the vertical stake that would support this cross-beam was already in place in the ground.

The condemned man was stripped naked, a further humiliation, and the beam across his shoulders was lowered to the ground. This threw his body backwards, because the straps or ropes tying him to the beam were still be in place.

According to the seriousness of his crime, the condemned man was either tied or nailed to the cross. Nails were reserved for the worst criminals.

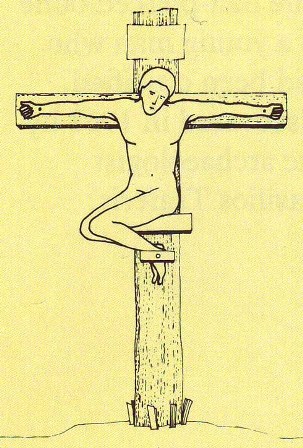

Reconstructions of crucifixion, based on the pierced heel-bone found at Giv’at ha’Mivtar

In Jesus’ case, a soldier drove a heavy, square, wrought-iron nail through the wrist, deep into the wood. When both wrists had been nailed, the beam was lifted into place at the top of posts already lodged upright in the ground.

It might lie across the top of the stake, forming a T, or be positioned part way down the stake, forming the traditional shape of a cross.

This second option must have been the way that Jesus was crucified, since two of the gospels (Matthew and Luke) describe an inscription that was fastened above his head at the top of the cross.

A small block of wood was positioned half way down the surface of the cross, so that it formed a support for the condemned man’s body.

Death

Many condemned men were left in this position, with their legs tied to the upright beam, but Jesus seems to have had his feet nailed to the wood as an extra punishment.

It made his death more brutal, but it also made it quicker, since the additional agony sent him into shock, while also making it more difficult for him to push his body upwards, to breathe. He also lost more blood, weakening him further.

Since he was effect hanging by his arms, his chest muscles began to go into cramp. He could breathe in, but it became increasingly difficult to breathe out. Carbon dioxide built up in his lungs and in the blood stream. He was horribly dehydrated. The pericardium, the sac surrounding his heart, filled with fluid, compressing his heart, and he died of heart failure and suffocation.

Since he was effect hanging by his arms, his chest muscles began to go into cramp. He could breathe in, but it became increasingly difficult to breathe out. Carbon dioxide built up in his lungs and in the blood stream. He was horribly dehydrated. The pericardium, the sac surrounding his heart, filled with fluid, compressing his heart, and he died of heart failure and suffocation.

Jesus died relatively quickly. Others were not so lucky. Death could be very painful and very slow, usually taking more than 36 hours.

Sometimes death was hastened by breaking the legs, and because of this crucifixion was also known to the Romans as ‘broken legs’. Cicero mentions ‘that it is quite impossible for Plancus to die unless his legs are broken (he is crucified as a slave). They are broken, and still he lives.’ (Cicero Philippicae XIII 12 (27).

Josephus, the ancient Jewish historian, called crucifixion ‘the most wretched of deaths’ (Wars of the Jews VII 202), and records that some victims survived even after several days on the cross (Josephus, Vita 75).

The Dead Christ, Hans Holbein

Burial

It is assumed that most people who had been crucified were buried in a common pit outside the city walls, but excavations in north Jerusalem have revealed a burial cave with the skeletal remains of a crucified man dating from the 1st century AD, at about the same time that Jesus died.

On the evening of his death, Jesus’ body was placed in a tomb by his family and friends.

The fate of other 1st century men who were executed as criminals is unknown. Their bodies may have been placed in unmarked graves, or claimed by their families, or simply placed on a rubbish dump.

Whatever happened, the fact remains that, apart from the significant find at Giv’at ha-Mivtar (see above) there is very little archaeological evidence relating to crucifixion.

See Bible Women: Major Events for information about death and burial in ancient times – what happened to the body of a family member who had died.

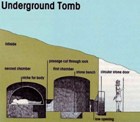

Diagram of a 1st century tomb cut into the hillside:

entrance, foyer and inner chamber

Crucifixion in art

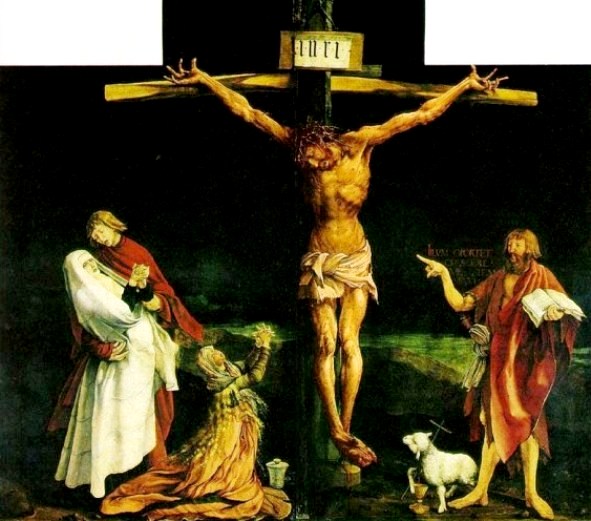

Folding altarpiece by Matthias Grünewald, the crucified Christ with Mary of Nazareth, John, Mary Magdalene, John the Baptist

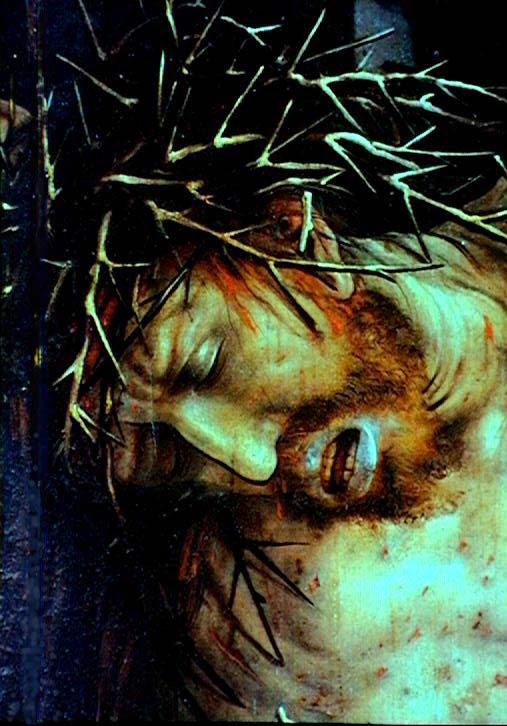

Above: details from Matthias Grünewald’s magnificent altarpiece ‘Crucifixion’.

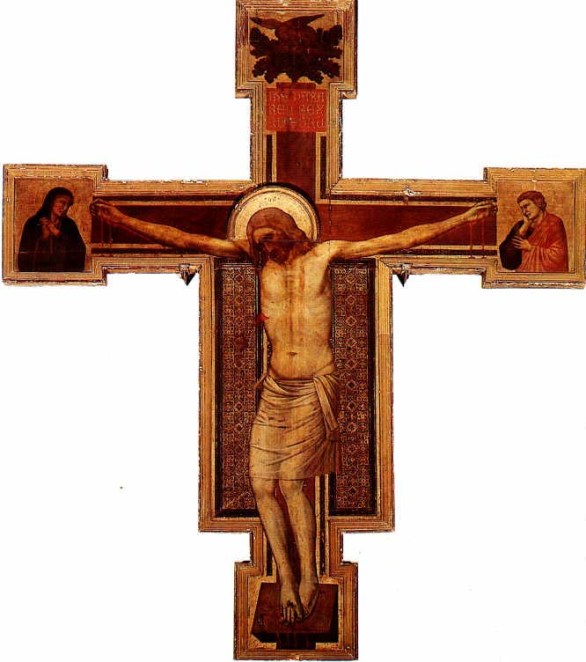

Artists sanitized images of the Crucifixion, leaving out or softening the reality lest they offend the viewer – see Giotto’s ‘Crucifixion’ above. There is little evidence of the torture Jesus endured during his Passion and Death

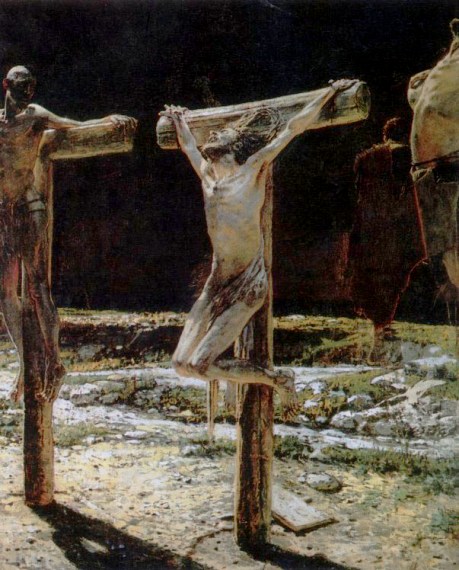

Crucifixion, Nikolai Ge (Gay), 1893

Francis Bacon’s disturbing ‘Crucifixion’ captures something of the horror of that event.

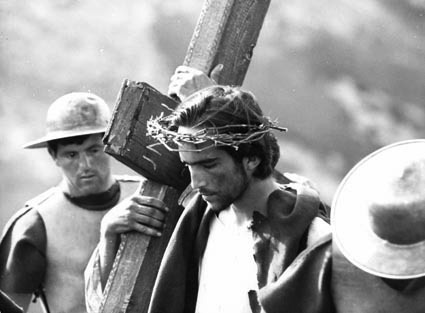

Crucifixion in movies

Modern films are sanitized to get them past the censors. This image from Pasolini’s ‘The Gospel According to St Matthew’ shows a calm and dignified Jesus as he makes his way to Calvary.

Mel Gibson’s ‘The Passion of the Christ’ was much closer to reality.

For more on these two films, and on other Bible films, go to

For more on these two films, and on other Bible films, go to

Bible Top Ten Movies

‘Crucifixion’ links

Watch Pasolini’s ‘Gospel of St Matthew’ movie – one of the best ever movies about Jesus

____________

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher