Farming in ancient times

How did farming begin?

Israel may have been the Promised Land, but much of it was dry and infertile. Farming was hard work – and at least 90% of people in the ancient world lived by working the land.

The story of the first human beings hints at this: the Hebrew word for ‘man’ is adam; the word for ‘earth’ is adamah.

According to the Bible story, the Hebrews were farmers (Cain), and nomadic herders (Abel). It was the conflict between these two groups of people that inspired the story of Cain and Abel. See Top 10 Bible Murders.

Farming was also important in New Testament times. Jesus talked often about the land and its products in his teachings, showing he was familiar with farming techniques. Matthew 13, for example, contains four farming parables. You can read about them at Famous Parables of Jesus.

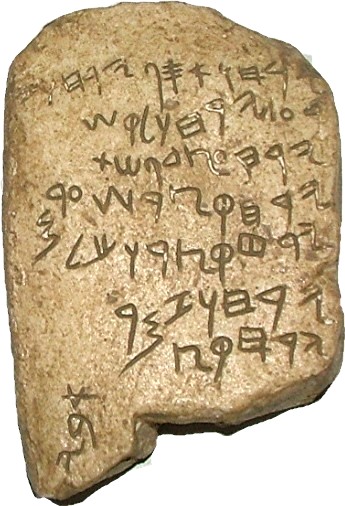

Ancient farming calendars

Gezer-Calendar, reproduction of the original ancient artifact

The Gezer Calendar (see right) is a limestone tablet about 4inches (10cm) tall. It dates from the time of Solomon, in the mid-10th century BC. It describes the agricultural cycle month by month, giving the tasks to be performed at certain times of the year.

- August and September are times of harvest

- October and November for planting

- February is devoted to cultivation of flax and

- March to the barley harvest, etc.

Note: the Gezer Calendar is deciphered at the bottom of this page. It has the farmer’s tasks for each month of the year.

What was the annual cycle?

The major festivals in Israel were closely linked with the farmer’s annual cycle.

- The Feasts of Passover and Unleavened Bread were celebrated at the beginning of the barley harvest.

- Fifty days later came the Feast of Weeks, or Pentecost, when the wheat harvest began.

- The Feast of Tabernacles, or Ingathering, took place when the harvest was complete.

Sowing and ploughing began in about the middle of October at the time of the early rains. This was followed by harrowing and weeding. The later rains were vital for ripening the crops, and the rainy season usually ended around early April.

Harvesting began with the barley harvest, around the middle of April. The gathering of the grain harvest, the summer fruits, and the grapes lasted until August and September, although the last olives were finally picked in November.

Irrigating the land

After settlement in Canaan the Hebrews became predominantly farmers.

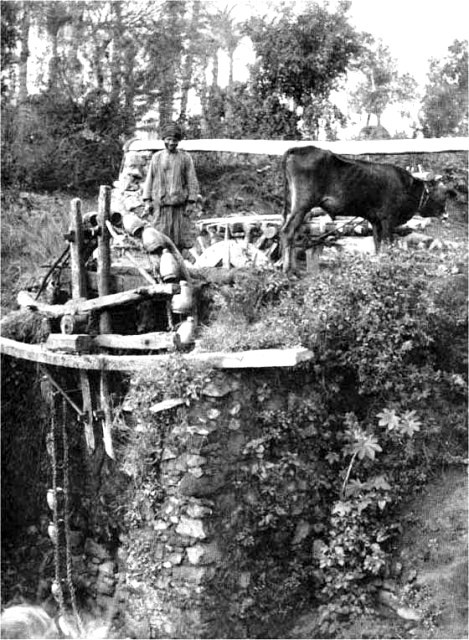

Drawing Water, example of a Shakeyehz: 1894 photograph

Canaan was surrounded by countries with successful farming methods – Sumerians in the Tigris and Euphrates valleys, and Egyptians in the Nile valley.

These countries had already mastered irrigation and cultivation methods – see Ancient Technology.

The main crops were

- grain

- grapes (for wine and dried fruit) and

- olives (for oil).

These three crops are mentioned over and over again in the Bible.

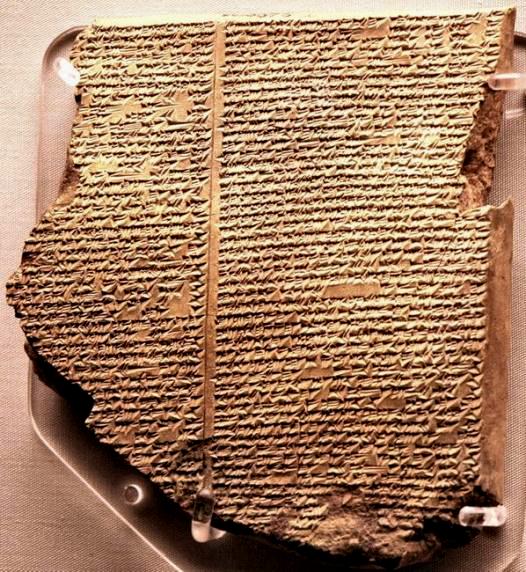

Assyrian clay tablet telling the story of the Gilgamesh flood

Unsown land was ploughed three or four times, suggesting biennial fallow, but the Hebrew sabbatical (seventh) year fallow was also important in promoting soil fertility.

About 30lbs/13.5kg of seed was used to a half acre of land (0.2 hectares). This is about half the quantity of seed normally used today.

Aerial shot showing traces of an ancient irrigation system in Iran

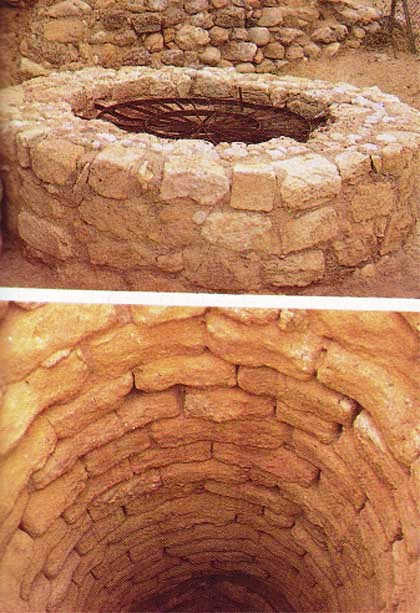

Above: Two images of a traditional stone well used to collect and store water

Ploughing

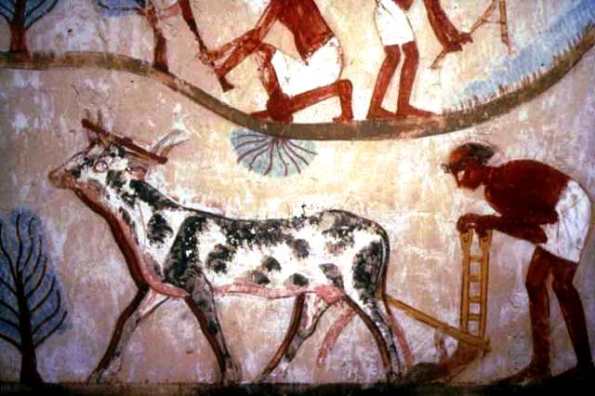

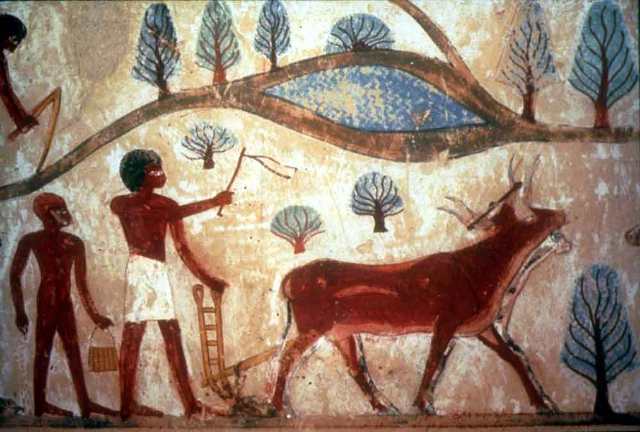

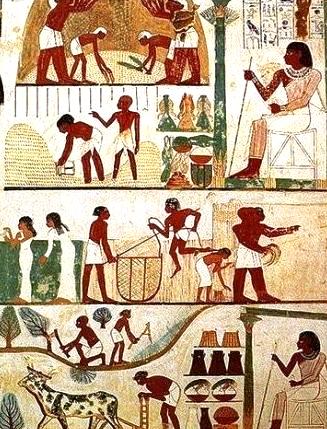

Wall painting from an official’s tomb in Thebes, showing a plough preparing land for sowing

Ploughing in the Plain of Jezreel, from a 1925 photograph. Jezreel had fertile farming land and was constantly fought over. Jezebel took some of this land from Naboth (1 Kings 21:1-16) , and she and her family were eventually murdered.

See Jezebel’s Story

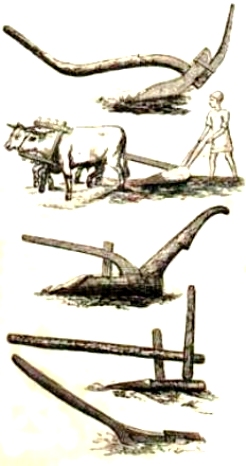

The useful plough

Where did ploughs come from? Who thought of them first?

The design of the plough developed from the hoe. Hoes were used by humans, but a plough had the advantage of being pulled by animals, which meant less gruelling work for the farmer.

Except for the plough-point, the plough was made of wood.

The early plough-points were made of bronze, but after the 12th century BC, iron plough-points started to replace bronze. The plough had either one or two handles, so that pressure could be applied by a downward push of the plough-blade. It was pulled by a team of oxen or a single beast.

Unsown land was ploughed three or four times, suggesting beinnial fallow, but the Hebrew sabbatical (seventh) year fallow was also important in promoting soil fertility.

Sowing the seed – how? when?

Sowing took place after the first rains had softened the ground. If the farmer tried to plough before the rain, the plough-blade could not dig into the ground.

“I shall give the rain for your land in its season, the early rain and the later rain, that you may gather in your grain and your wine and your oil. Take heed lest the anger of Yahweh be kindled against you, and He shut up the heavens, so that there be no rain…. (Deuteronomy 11:13-17)

There were two methods of sowing seed:

- by broadcasting the seeds by hand

- or using a seed-drill.

Two animals draw a plough as the ploughman encourages them with a whip. Notice the boy behind him, carrying a satchel containing seed for planting.

- For the first method, the farmer walked along the furrows at a constant pace pulling handfuls of seed from a bag at his side and throwing them over the soil.

- Several people might be involved for the second method: one to direct the plough and push the handle down into the soil, one to direct the animals, and a third person to hold the seed bag on his shoulder and drop the seeds into the funnel which pointed down to the soil. These seeds would fall behind the plough-point, so that they were covered by the falling soil.

The animals were yoked together with either a single yoke or a double yoke wih bars over and under the neck. An ox goad, a long staff with a nail or metal tip, could be used to control the unfortunate animals.

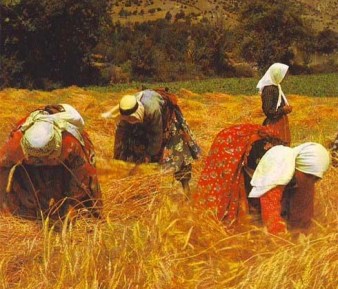

Reaping the crop

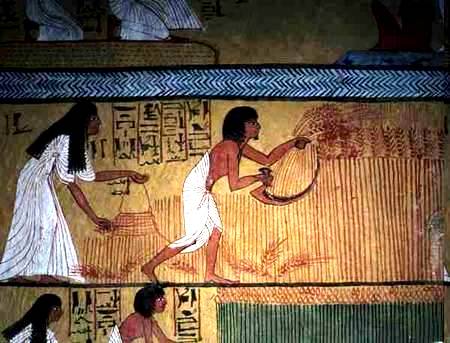

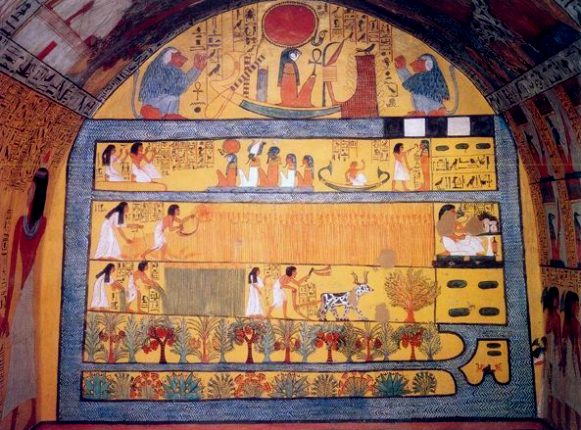

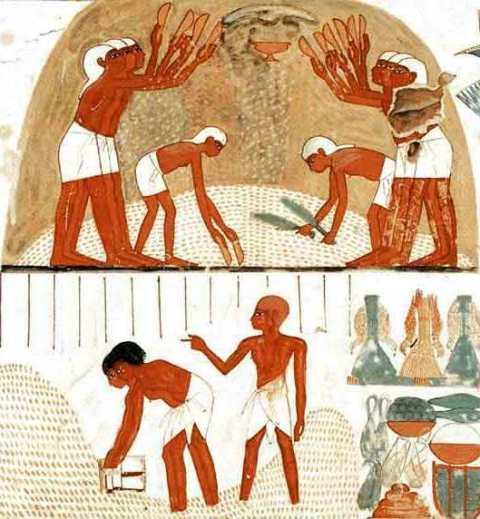

Tomb of Sennedjem, Amarna: cutting ripe grain with a blade

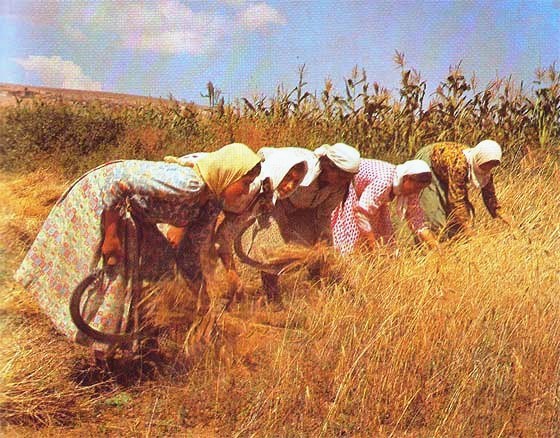

Harvesting was intense work, and itinerant workers had to be hired especially for it.

Harvesting the crops involved

- cutting the standing grain with scythes,

- tying the stalks into sheaves, and

- transporting the harvested crops to the threshing area.

Reaping was done with a sickle held in one hand while a bunch of stalks was seized with the other. The reapers were led by a foreman, and behind them came other people who were taking part in the harvest – the young men and women.

For an example of this, see the story of Ruth and Naomi.

This painting (above) covered all of one wall in the Tomb of Sennedjem, at Amarna. It shows several phases in the process of farming, including a prayer ritual offered to the gods. The prophet Isaiah referred to the various processes involved in growing grain, saying that it was an occasion for wonder and praise of God. (28:23-29)

Who got the grain?

There were others who were not directly involved with the harvest – the poor, who were allowed by religious law to glean any grains that the reapers dropped or missed.

Religious law specified that a corner of the field had to be left for the poor – this part of the field could not be harvested by the landowner (Leviticus 19:9, 23:22).

The workers were given food – bread dipped in vinegar and parched grain.

Modern-day women harvesting with sickles

Threshing the grain

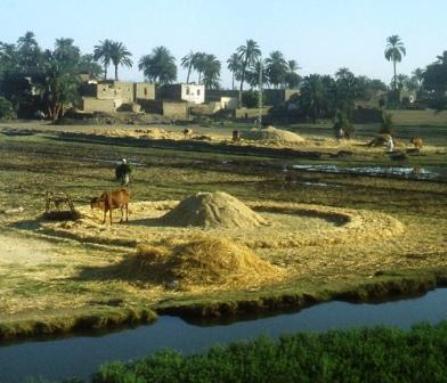

The separation of the grain from the stalks was done on the hard, flat rock of the threshing floor. This was usually located outside the city or town, in a spot where the prevailing westerly wind could help with the winnowing.

A threshing floor surrounded by a low stone wall to contain the grain

Woman threshing grain, Israel, 19th century photograph

The threshing floor was a wide, open space also used for public functions.

For the most famous Bible story involving a threshing floor, see the love story of Ruth at Bible People: Ruth

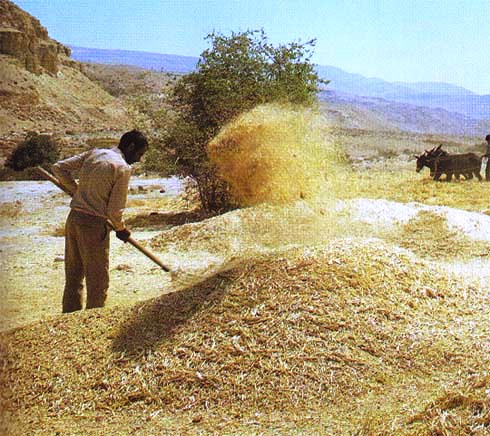

Winnowing – nothing was wasted

Theban tomb painting, grain being winnowed

After winnowing was completed, the farmer was left with several products.

The first, of course, was the grain itself.

But there was also coarse thick straw suitable for kindling, or as binding in brick making.

There was also a finer sort of straw that was the main component of animal fodder. The fine residue of dust/powder left on the threshing floor was used as packing around the grain-filled storage jars.

Winnowing the grain, threshing with donkeys

Wine and oil production

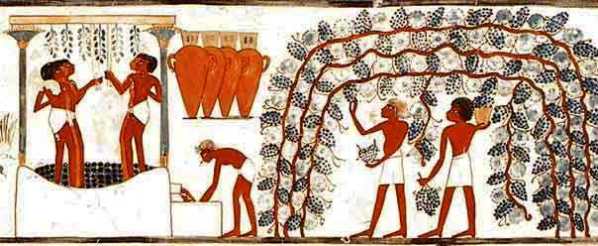

The Old Testament law let people eat grapes while they were collecting them, but not put them in their own baskets while in someone else’s field (Deuteronomy 23:24).

The grapes were mainly used for wine, but some were dried as well for later use. Isaiah 5:1-7 gives some idea of the hard work involved in preparing and cultivating vineyards.

As the fruit began to ripen from July onwards, people used stone towers to keep watch for both human and animal intruders. Harvesting the grapes and making wine were great social occasions.

A press was used to crush the oil from the olives after they had been harvested – see Ancient Technology. This press had a beam inserted either into a niche in a wall or into a large stone. Weights were tied to the other end of the beam. The olive baskets were placed under the beam, inside a collection basin.

In later times, during the Roman occupation of Palestine, large stone wheels were used to press oil.

Theban wall painting: grape-vines trained over a trellis, then crushed in a vat.

The Bible credits Noah with inventing wine, but Bible Art: Noah shows what happened then!

The land and its crops

The Bible praises the fertility of the “promised land”, and in fact remains of ancient settlements demonstrate that the land could support large numbers of people.

Field Crops

The principal crops were grain, wine and olive oil (Dt. 7:13; Hos. 2:8).

A large slab of rock used as an ancient mortar for crushing grain

Grain, i.e. wheat, barley and spelt, has been found in the ruins of even the earliest settlements, going back to prehistoric times, while mortars were found at El-Wad cave. Many authorities agree that grain was first cultivated by people living at the foot of Mount Carmel in the Mesolithic Age (8th millenium BC) or perhaps even earlier.

Stone lined grain silo at the ancient city of Megiddo; see inset for steps leading down into the storage area

Grain silos have been found in the underground dwelling caves of prehistoric people of the Chalcolithic Age (4th millenium) near Beersheba (Tel abu Matar). The silos, bell shaped and with a capacity of 40-55 litres were found both in the living chambers and the connecting galleries.

From the later Bronze and Iron Ages, silos were dug into the floors of houses for the storage of grain from one year to the next and larger granaries serving a communal or administrative purpose become a commonplace of excavations.

Of these, the best preserved and largest is the stone lined silo at Megiddo (see above), from the time of Jeroboam II (8th C. BC), or the granary excavated at Gezer.

Ploughing and harvesting – how?

The earliest fields were worked with hoes.

In the Stone Age these were made of a sharpened flint attached to a wooden stick. Wooden implements, digging sticks, etc. were used earlier but the remains of this “wood age” have rotted and disappeared from the soil of Israel.

Bronze hoes from Kobuleti, circe 1300-1200 BC.

Presumably, stone implements were used along with wood from the earliest times, as shown by hand-axes used by men who lived in caves several millenia before the Mesolithic and Neolithic ages.

But bronze replaced stone, and tools improved.

The biggest step forward came with the introduction of the plough. Ploughs were made — as they still are today in primitive communities — from a piece of wood, later tipped with metal, drawn by one or two oxen.

The biggest step forward came with the introduction of the plough. Ploughs were made — as they still are today in primitive communities — from a piece of wood, later tipped with metal, drawn by one or two oxen.

Then by the 11th century BC (Late Iron Age), iron had been introduced.

At first, manufacture and repair of iron implements was monopolized by the Philistines. They guarded this technology jealously, because it gave them the edge on other groups.

Harvesting the crop

From the Neolithic to the late Bronze Age, flint sickles were used in harvesting.

About 1100-1000 BCE iron began to be used for all types of tools and weapons and iron sickles displaced the flint ones. By the time of the divided monarchy, it is clear from the number of iron agricultural tools that have been found that the metal was readily available to everyone.

Even so, a plough of this type could only scratch the surface to a depth of 7-10 cms. It could not turn the soil into a furrow.

Flint sickles, flat grinding stone, stone ax with wooden handle

Sowing

The basic grain crops were wheat and barley. The wheat was of a very poor variety compared to modern strains. Rye seems to have been unknown. By the time of the monarchy, other seeds such as spelt and flax were also sown.

Sowing was done by scattering the seed by hand. The land was then ploughed again to cover it, branches being dragged behind the plough to smooth the ground over the seed, (Is. 28:24-5; Job 39:10).

It might take weeks of laborious work for the Israelite to sow a small field.

Vineyards

Vineyards came second in importance to fields, but they needed a great deal more care and evoked a strong attachment in their owners — as witness the story of Jezebel and Naboth’s vineyard.

A vineyard was a precious possession. It called for much hard work — it had to be weeded and fenced and a stone watch tower erected to guard it against animals and marauders — and then years of waiting were needed before it came to fruition.

A vineyard was a precious possession. It called for much hard work — it had to be weeded and fenced and a stone watch tower erected to guard it against animals and marauders — and then years of waiting were needed before it came to fruition.

Vines were grown sometimes as bushes or small trees; in other cases, fig trees might be used to support the vines. From this came the phrase “every man under his own vine and under his fig tree” (1 K. 4:25) as a symbol of an ideal of social well-being.

The “Song of the Vineyard” (Isaiah 5) is a moving parable of the care demanded by a vineyard, with a vivid description of the agricultural operations involved. It is typical of Isaiah that he used such a parable to plead for justice for the small man and the peasant, “Woe to those who join … field to field” (5:8).

Nothing remains of these ancient vineyards.

The little heaps of stone which cover many slopes in the Negeb were once taken for vestiges of vineyards or grapevine hills, but this is now known to have been a mistake. They were used to divert rain water from hill slopes to terraced “wadis” or cisterns. What do remain are the enormous stone grape-presses.

Grape Presses

When the grapes were ripe, they were gathered and dumped, one or two baskets at a time, into a small vat whose floor sloped down towards a small basin. The grapes were trampled by foot to extract the juice.

Some of the grape presses found in the Judean lowlands (the Shephelah), may also have been used to extract olive oil by a similar method.

Reconstruction of a Roman wine press

Wine presses cut in solid rock abound in Judah and Samaria. Some are single square vats for treading out the grapes.

Others had three sections,

- one where the grapes were trodden,

- one for refining and

- one for storing the juice.

One of the oldest of these is the 7th century wine press at Gibeon with dipping basin and stone trough, left, and openings to four vats – see Ancient Technology.

Fruit trees – main source of sugar

Figs were a staple of the country’s diet, being one of the main sources of sugar.

An alternate variety was the sycamore fig, grown mainly in southern Palestine. Amos (7 :14) was “a dresser of sycamore trees”, meaning that he punctured the green fig while still on the tree, to ensure the softening of the fruit, after which it rapidly ripened and became edible.

Fig syrup, like that of carobs, was used for sweetening, while dried and pressed figs were a convenient preserve, easy to transport and acceptable as gifts. The wily woman Abigail gave David two hundred cakes of pressed figs.

Figs were also said to have medicinal value: a poultice of figs was applied to Hezekiah’s boils, on the advice of Isaiah.

Olive trees for oil

These were of great importance for ancient Israel’s economy. Olive oil is used in

- cooking

- for lamps

- for cosmetic purposes

- as a cleaning agent and

- in the treatment of sprains and wounds.

To extract the oil, the ripe olives were put into the vat and then either trodden or pounded with a stone or pestle. The oil produced in this way was the finer ‘beaten oil’. The pulp left behind was then placed under heavy weights to squeeze out the rest of the oil.

Reconstruction of a large stone olive press

Commercial oil presses had large vats which would be filled with olives and heavily weighted. Presses like this dating from the 10th to 6th centuries BC were found at Debir and Beth-Shemesh. Part of the payment Solomon made to Hiram, King of Tyre, for cedar wood and carpenters supplied for the building of the Temple was in olive oil.

Other fruit trees were the date palm, pistachio, apricot, mulberry and pomegranate.

The Cycle of Seasons

Ancient Egyptian farmer’s calendar.

Because of the tremendous importance of farming, the year was divided and festivals timed in relation to the farmer and his needs.

Even where festivals later acquired a religious and national significance, they kept traces of their original function as the festive seasons of an agricultural community.

The biblical civil calendar gave the months numbers, counting from the first (fall/autumn) month to the twelfth. This system originated with the Israelites and replaced the Canaanite nomenclature.

The peasants, whether Canaanite or Hebrew, listed the months according to the tasks to be performed in the different periods of the agricultural year.

The Egyptian farmers’ calendar above does the same thing, showing land preparation, ploughing, reaping, winnowing and grain storage.

The Gezer Calendar

You can see this calendar in the stone tablet from Gezer (top of page) It is assumed to be part of a 10th century BCE schoolboy’s exercise. It is not an official calendar.

In seven lines, it lists the months and seasons as:

- 1: 2 months Olive Harvest (Sept/Oct or Oct/Nov), first the picking of the olives then the pressing for oil.

- 2: 2 months Sowing: The next two months (Nov./Dec or Dec/Jan) come, in Israel, after the first winter rains and, as a rule, after the ploughing, done at the end of October and early November. This was the grain-sowing season.

- 3: 2 months Late Planting: January to March was the time for sowing millet, sesame, lentils, chick peas, melons, cucumbers and so on.

- 4: 1 month Hoeing: This was especially the period for cutting the flax. This was done with a hoe as the plants must be cut close to the ground so that the full length of the stalk can be used, when dried and treated, to make thread and cloth.

- 5: 1 month Grain Harvest: Barley is harvested in April in the south and in May in the north. Wheat and spelt come later in May/June. The grain was cut by a sickle, made before the 10th century BC from flint chips set in a haft made of wood or bone. Later, a small curved wooden blade was affixed to a wooden handle. The grain was separated from the straw and husks by spreading the cut plants on a specially prepared threshing floor outside the village and then driving oxen round and round over it, pulling a threshing sledge which might be flat or on small rollers. The grain was then winnowed and sieved, and finally stored in large jars. Rooms full of such jars are not uncommon in excavations.

- 6: 1 month Festivals: Seven weeks from the beginning of the grain harvest (Dt. 16:9) or at about the time it was completed, a pilgrimage was made to the sanctuary bearing an offering of “first fruits” for the festival of Pentecost (Shavuoth). In later usage, the Hebrew terms for “early harvest” or “first fruits” have acquired the wider meaning of “choice” fruits or produce.

- 7: 2 months Vine Tending: During the hot summer months of June/July or July/August, after the grain harvest, vines were pruned and the vineyards weeded and cleaned in preparation for the grape harvest.

- 8: 1 month Summer Fruits: The last month of the agricultural calendar (August/Sept.) was devoted to harvesting summer fruit, especially grapes, figs and pomegranates.

According to the oldest liturgical calendars, (Ex. 23:14-17; 34:18-23), the first month, Nisan, during which the feast of Unleavened Bread was celebrated, began in the spring, approximately March-April in modern terms.

Search Box

![]()

Ancient Farming links

____________

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher