What did Israelites believe?

Bible Study Resource

Officially, the Hebrews worshipped Yahweh, the formless power who created and governed the universe. Yahweh was the focus of, and reason for, the Temple in Jerusalem and the priesthood that served it.

But over and over again the Old Testament describes something different – the people turning to other gods.

But over and over again the Old Testament describes something different – the people turning to other gods.

This fickle behaviour horrified the Bible writers. They likened the Hebrews to a woman who deserts her husband for other men (Jeremiah 3:1-10) – ‘you have played the whore with many lovers’.

Jeremiah describes how she (the Hebrew people) ‘went up on every high hill and under every green tree, and played the whore there’ and committed adultery ‘under every stone and tree’.

What does Jeremiah mean?

Standing stone, Tel Gezer

Hebrews would have understood that ‘tree’ and ‘stone’ were code for Canaanite fertility worship.

- A ‘tree’ meant Asherah, the earth mother goddess of fertility

- a ‘stone’ was a matzebah – an upright stone serving as a phallic symbol, and used in the worship of Baal (see right).

Sex was not taboo in the Canaanite practices. Quite the reverse.

Sex, witchcraft were taboo

There were three areas in which the people apparently failed:

- they remained faithful to the nature gods, and the rituals of the fertility cults

- they wanted to be able to communicate with the dead

- they believed in witchcraft and/or sorcery – indeed, Jesus of Nazareth was accused of being a sorcerer.

Why did they do this?

Ordinary people often tried to use rituals to control problems in their daily lives.

Ordinary people often tried to use rituals to control problems in their daily lives.

- They were anxious if it did not rain or if it rained too much

- they were afraid of death

- and they sought to control frightening aspects of daily life such as illness or accidents.

We are no different: we worry about climate change, we try to avert death at all costs, and we believe wholeheartedly in medical remedies and the power of doctors to cure us.

Keeping bad luck away

People in the ancient world tried many different ways to control the forces of Nature. Every country had different rituals and religious practices to keep bad luck at bay and coax Nature into behaving in a way that would help, not harm, humanity.

At right is a Roman shrine from Pompeii. It was built to honour the lares, the spirits protecting a family and household. Offerings of food and drink were made every day to these spirits in the hope they would bring prosperity and good luck.

At right is a Roman shrine from Pompeii. It was built to honour the lares, the spirits protecting a family and household. Offerings of food and drink were made every day to these spirits in the hope they would bring prosperity and good luck.

In many ways, the teraphim hidden by Rachel are similar to the Roman lares (see Women in the Bible: Love Conquers All – Rachel

We’re not much different. In the modern world we offer prayers to God to keep us from harm, protect our families, give us security. ‘Touch wood’ we say, to avert back luck.

Coping with grief

The burial practices of each country helped people to cope with the grief of losing people they loved, and with anxiety about the future.

Witchcraft and sorcery gave them a sense of control over possible disaster. A spell or charm could, they believed, ward off bad luck or illness, caused by malignant forces in the universe.

Feeling safe

People have tried to control the forces of Nature since prehistoric times. They still do. The fertility cults were practised in the ‘high places’ – temples and altars built on the tops of mountains; ‘on the mountain heights, on the hills, and under every leafy tree’ Deuteronomy 12:2.

The prophets of the Old Testament taught the people that prosperity, peace and safety depended on Israel’s obedience to God, and that people themselves had an obligation to help the unfortunate, the poor and the weak.

Despite this, many of the people still found the ancient religious practices attractive, and continued to worship other religious deities or forces of Nature right throughout the biblical period.

Stone pillars

Canaanite Standing Stones at Gezer

Stone pillars are the most ancient evidence we have of organized religious practice. We know they were put there

- to honour supernatural forces

- to give thanks for some favour granted

- to mark territorial claims or boundaries.

Sometimes they could be for all three reasons. Jacob, a complex man searching for God, set up pillars near Shechem and Bethel, and one as a token of his covenant with his father-in-law Laban (Genesis 31:44-45).

The stone itself gave witness to the contract between God and the person who erected it – visible tangible evidence for all to see.

Sacred ‘High Places’

The high or holy places at which God revealed Himself to the Patriarchs were associated with natural objects:

Upright stones at Gezer

- trees, at Shechem, Beersheba and Hebron

- springs and wells, at Beersheba

- upright stones, at Bethel and Shechem.

Abraham planted a tamarisk tree near Beersheba and called the site Adonai ‘El’Olam (My Lord, God of the World; Genesis 21:33). The site of God’s revelation to Hagar, is called ‘Ata ‘El Ro’ee’ (You are a God of Seeing; Genesis 16:13).

Does this association of God with natural objects suggest the survival of animistic beliefs in the religion of the Patriarchs?

It’s difficult to say. The Patriarchs were commemorating an event, but they were not using the spot to hold a festival, or celebrate a holy day with a sacrifice, though we do know of ceremonies of libation of oil or wine on newly built altars.

These altars were the ancient predecessors of shrines, temples and the institution of the priesthood – all the later religious paraphernalia of ritual and sacred space.

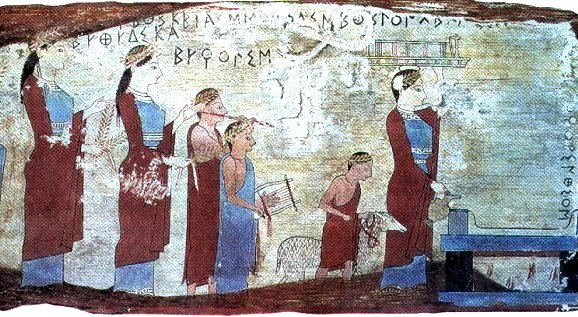

A family group (with priestesses?) brings a lamb for sacrifice, Greece 530BC. This sort of ritual often marked an important event or milestone.

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher