Herod’s Jerusalem Temple

Until the lst century BC, the Jerusalem Temple was a fairly modest and battle-scarred place of worship.

But Herod the Great changed all that. He created one of the most glorious buildings of his time. And that is really saying something, when you think of the temples and palaces in ancient Rome.

The project was begun in 20BC (the 17th or 18th year of Herod’s reign). The major part of the reconstruction was accomplished in ten years, though additional work went on for many years after.

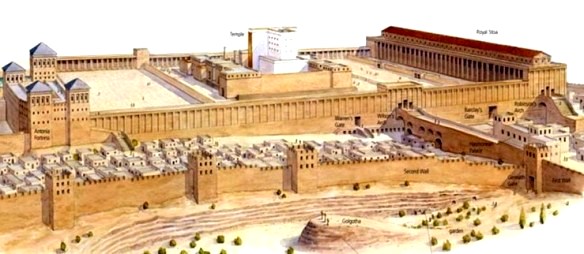

The Herodian Temple was constructed over and around the existing modest building. Built on a high esplanade and surrounded by columns and beautiful gates, its shining white stone could be seen for miles in every direction.

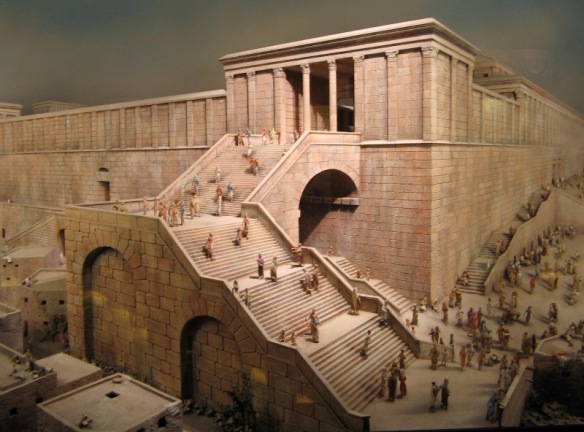

The southern face of the Temple, showing the grand stairway leading to the stoa or entrance portico. Model by Professor Avi-Jonah

Herod did not alter the size of the inner Temple, i.e. the one rebuilt by the post-Exilic community, probably a later version of Solomon’s Temple, nor did he change its general pattern. But he

- doubled the area of the outer courts

- by smoothing the rock surface and filling in the steep south- eastern slope (work which had actually begun in the days of Solomon).

- and he levelled and filled the area between the Tyropeon Vale and the Temple mount at the southwestern corner.

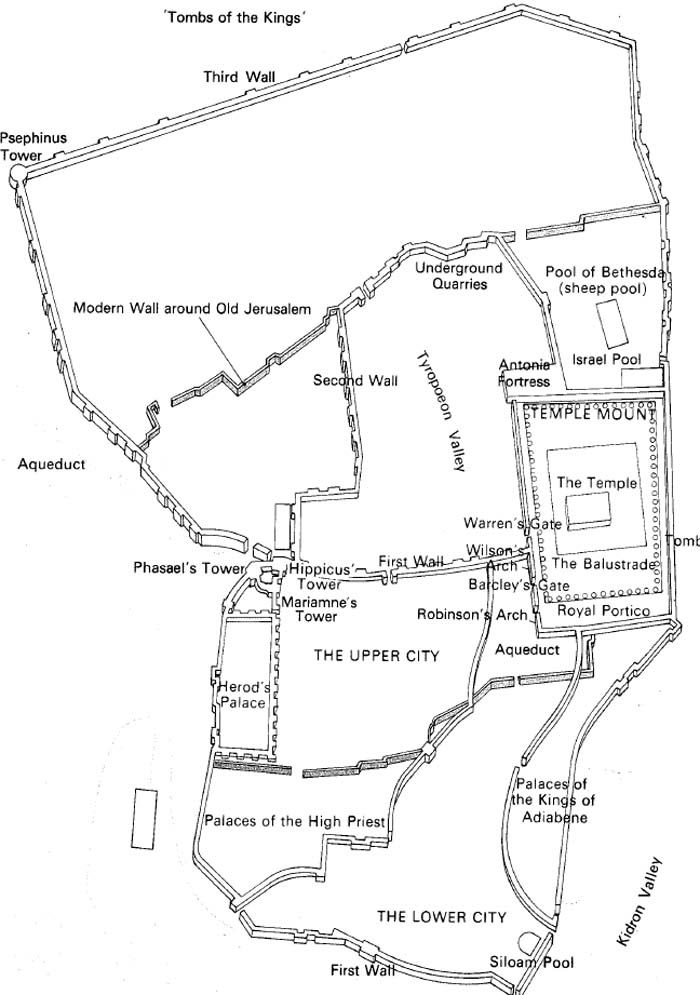

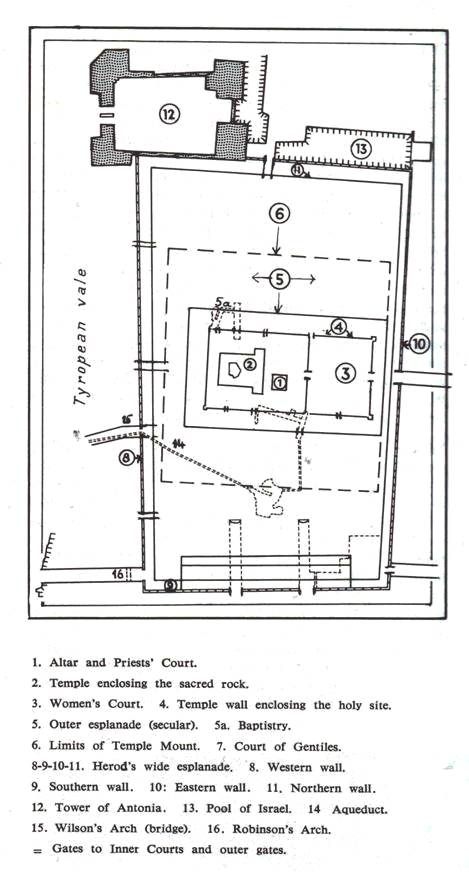

Layout of the city of Jerusalem in King Herod’s time

The remains of the southeastern supporting walls and those of the western end of the esplanade (the Wailing Wall of today) are still visible.

The Temple Courts

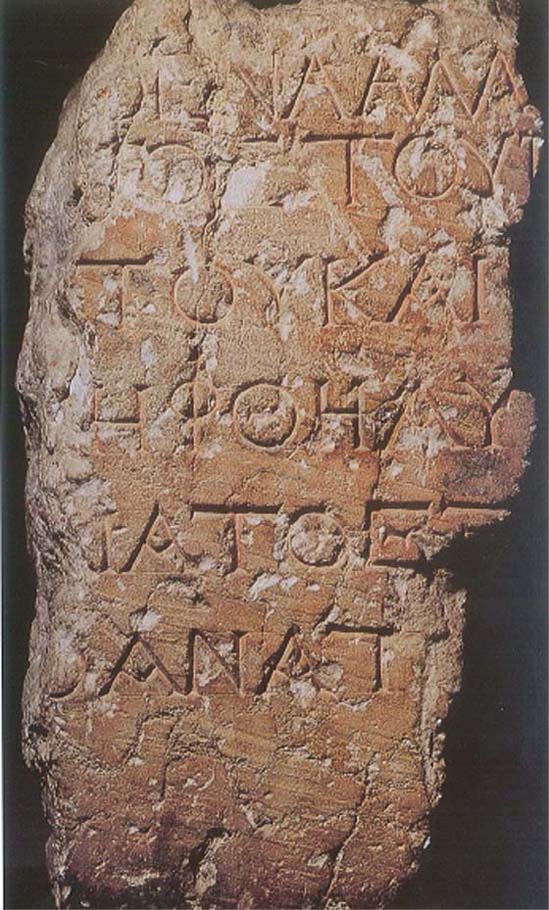

Inscription forbidding Gentiles to go past a certain point in the Temple precincts

The Temple was not just for worship. It was also a military stronghold. The whole area was surrounded by a strong outer wall for purposes of defence.

Inside this outer wall was a free belt, the outer court, which in Herod‘s time was known as the Court of Gentiles.

Then came a strong fence marking the boundary of the inner sanctuary. No alien was permitted to cross this boundary, as attested to by an inscription dating from Roman times which read “No foreigner is allowed within the balustrade and embankment about the sanctuary. Whoever is caught will be personally responsible for his ensuing death.” (see Acts 21:31ff). A photograph of this inscriptions is shown at right.

The court was surrounded by internal porticoes which were connected with the Tower of Antonia to the north-west. In the largest of the porticoes, money changers and merchants carried on their business (Mark 11:15-17).

The inner court contained

- a section for women

- another for male worshipers

- and still another court for the priests

- the main altar surrounded by chambers used for various purposes connected with sacred ritual, sacrifice, ablutions, etc.

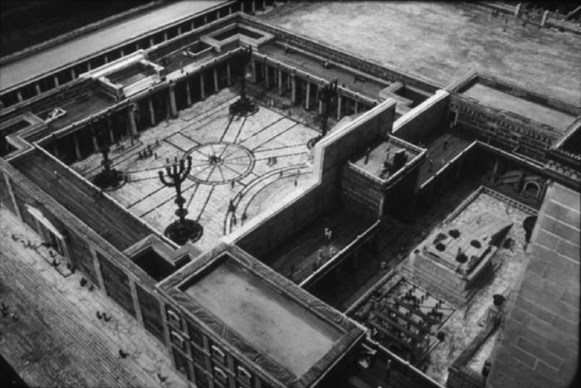

The Women’s Court (with patterned floor) and surrounding Court of the Gentiles in the Jerusalem Temple (reconstruction by Alec Gerrard)

At least eight gates opened onto the sacred area and it was approached by two bridges from the east and two from the west.

The women’s court communicated, via the Nicanor Gate, with the Gate of the Israelites, and was in effect part of the Court of the Priests and the scene of mass-assembly during the festivals.

Also adjoining were the priests’ quarters and the Chamber of Hewn Stone (lishkat hagazit) where the Sanhedrin sat.

Most sacred of all, as in the First Temple, was the Holy of Holies.

Layout of the Temple precinct in the 1st century AD

The Temple

The Temple itself was divided into

- a hall (Eliam)

- a shrine (Holy Place) containing the incense altar, shewbread table and the seven-branched candelabrum (menorah), and

- the Holy of Holies, dark and empty and entered only by the High Priest on the Day of Atonement through a veil consisting of two parallel curtains.

Store chambers for treasures were in the north, west and south sides of the Temple building. They were used as deposit vaults, protected chiefly by the sanctity of the place and the awe inspired by the sacred surroundings.

The area of the completed Temple and grounds was 34 acres in extent. The northern wall was 351 yards long and the southern wall 309 yards long, while the eastern and western walls were respectively 518 and 536 yards in length.

Despite the bitterness against Herod as a person and as a ruler, Jewish writers (in the Mishnah, the New Testament, and Josephus) could not minimize his achievement in rebuilding the Temple. There was a popular saying, ‘He who has not seen Herod’s Temple has never seen a stately structure’ (Sukkah 516).

Modern-day reconstruction of the Temple built by Herod the Great

Facade of the Temple, from a coin struck by Bar Kochba in 132AD, long after the Temple itself had been destroyed. Reconstructions of the 1st century Temple are based on this image.

The Destruction of the Second Temple

After Herod’s time, Jerusalem and the Temple were under foreign domination much of the time.

The High Priests were civil rulers, appointed by the central authority; they collaborated with Rome, became worldly, and were compromised by these connections.

The Temple as citadel and refuge

Under the rule of the Roman procurators, the Temple area became the scene of bloody clashes which usually took place during the three pilgrimage festivals.

One act of overt opposition against Rome was the cancellation of the daily sacrifice in honour of the Roman emperor. This act may be regarded as a prelude to the Great Rebellion.

The Arch of Titus in Rome has a carving of Romans carrying a trophy of war: the Menorah from the Temple in Jerusalem

During the siege of Jerusalem, the Temple was the chief bastion of the Zealots who conducted a desperate struggle against the Romans.

But all the heroism of the Zealots was to no avail. The Romans stormed the Temple area after long and bitter engagements attended by heavy losses, and in 70AD the Temple went up in flames.

The great menorah and other temple trophies were taken as booty by the Roman troops to Rome, depicted on the Arch of Titus (see right).

The day of the destruction of the Second Temple, the 9th of Ab, also the date of the destruction of the First Temple, became from then on a day of mourning and fasting among Jews everywhere.

The Western or Wailing Wall

The only remaining section of the Temple buildings erected by

Herod the Great is the Western or Wailing Wall

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher