Death & burial in the ancient world

What happened when you died?

People in ancient times did not believe that you simply vanished.  Death might mean the loss of vitality and strength, but so long as the body or at least the bones remained, the soul or nefesh still existed.

Death might mean the loss of vitality and strength, but so long as the body or at least the bones remained, the soul or nefesh still existed.

What happened to your soul?

The nefesh sheltered in a place called Sheol – the subterranean home of dead souls (Genesis 44:29; Job 10:21 ff; Isaiah 14:9 ff.).

Why go to the trouble of burying a dead body?

People thought the soul could feel what was done to its dead body, so it must be given honourable burial. It could not be burned, or left as prey for wild animals. If it was, this would bring a curse on the living.

Animals mourn the death of someone they love, but only humans bury their dead. It’s as if we care for the people we love even after they die.

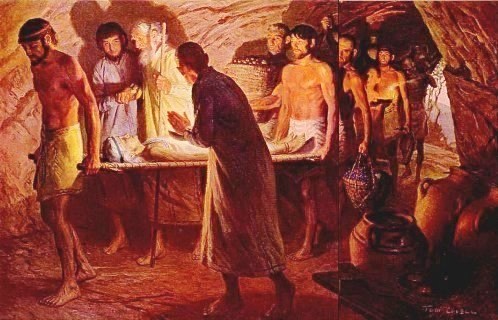

The burial of Sarah, great foremother of the Jewish people

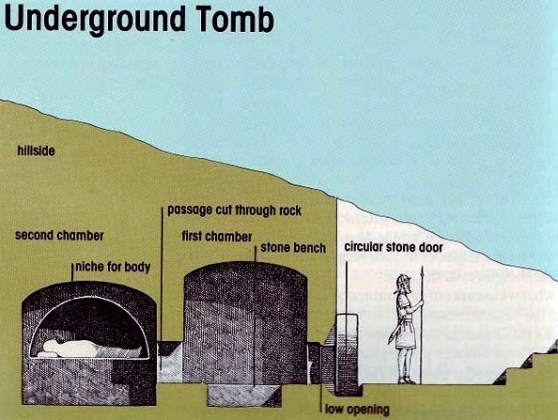

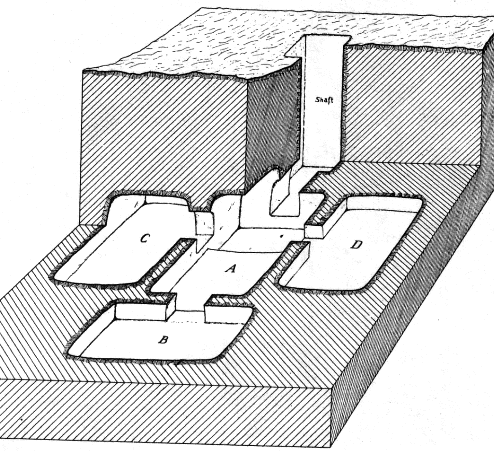

Design of a Roman-era tomb. The front chamber could be extended with the addition of secondary chambers

Ancient tombs

- In ancient Israel, tombs and catacombs were homes for the dead. They held the body until it decomposed, then the bones were stored in a central pit or in an ossuary (bone box).

- Tombs were cut into the rock, usually with a small central room and recesses for bodies.

Why have a tomb?

Animals mourn the death of someone they love, but only humans bury their dead.  It’s as if we want to preserve the people we care for even after they die.

It’s as if we want to preserve the people we care for even after they die.

Tombs began as circular huts in which the body was placed, along with tools and personal goods.

As time passed, tombs came to be built of more durable materials, like brick and stone. They were domed or rectangular, copying the shape of the houses.

You can’t take it with you?

You could if you were a king or queen. They were provided not only with sumptuous funerary goods (see jewels from the royal tomb at Nimrud), but also with servants to look after them in the afterlife. The tomb of Queen Shub-Ad of Ur (where Abraham originated), contained the bodies of more than sixty of the queen’s attendants.

In early Christian communities, the tomb was seen as an earthly symbol of the heavenly home. Roman catacombs are decorated with scenes of the deceased, now in Paradise.

Funeral Rites

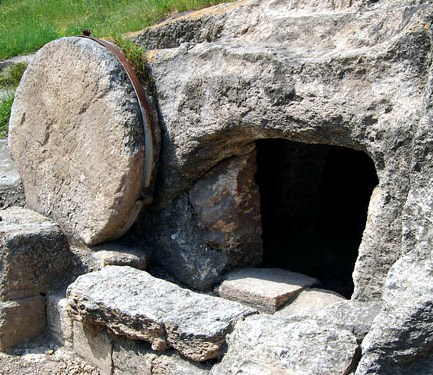

The tomb of Lazarus, entrance

To the Jews a corpse and the tomb which contained it were both unclean. The corpse was inescapably doomed to corruption. It contaminated everything and everyone who came into contact with it.

Death and religion

- Some of the customs related to funerals, e.g. the wearing of sackcloth or fasting, are also found in penitential rites and must therefore have a religious significance.

- The self-mutilation and shaving of the head condemned by the Torah (Leviticus 19:27-28) also had a religious meaning, although it is not easy now to know what it was.

Food offerings placed in the grave — a custom which the Israelites followed for a time in imitation of the Canaanites — bear witness to a belief in a life after death, as well as affection towards the person who had died.

Anyone who died had a right to receive these marks of respect. It was the duty of his relatives to carry them out. This was especially true when parents died. The Decalogue laid down specific rules about the duty of honouring dead parents.

Ancient Mourning Customs

Many of the rites following in surrounding countries were forbidden by the Law of Moses because they seemed idolatrous and, moreover, involved acts of desecration of the human body.

For example, Deuteronomy 14:1 commands the Israelites: “you shall not cut yourselves or make any baldness on your foreheads for your dead.”

- Cutting the hair,

- shaving the beard or

- lacerating the skin in especially sensitive places were all forbidden.

Exaggerated mourning was prohibited to priests who were not even permitted to let their hair grow during the period of mourning (Leviticus 10:6). A High Priest, indeed, was forbidden to mourn at all and might not even approach the bodies of his dead mother and father for fear of the defilement which was involved in touching a corpse.

Did people do as they were told? No. The various prohibitions were not altogether successful and many forbidden customs were followed (see Jeremiah 16:6; 41:5; Amos 8:10; Micah 1:16).

Certain mourning customs were, of course, permitted.

- From the earliest period, the close relatives of the deceased would gird their loins with sackcloth and sit upon the floor (Genesis 37:34; II Samuel 3:31; Lamentations 2:10).

- The head was sprinkled with earth, dust and ashes (II Samuel 1:2; Esther 4:1), or at least covered (11 Samuel 15:30; Jeremiah 14:3).

When David learned of the death of Absalom, he covered his face (II Samuel 19:4); when Saul and Jonathan were killed, he tore his clothes and wept and fasted until evening. Those who were with him did the same (I I Samuel 1:11-12).

When David learned of the death of Absalom, he covered his face (II Samuel 19:4); when Saul and Jonathan were killed, he tore his clothes and wept and fasted until evening. Those who were with him did the same (I I Samuel 1:11-12).- At the news that all his sons had been killed by Absalom, he ‘tore his clothes and lay on the earth’ (II Samuel 13:31).

- According to Ezekiel (24:17) it was customary to bare the head, cover the ‘lips’ i.e. the lower part of the face and go barefoot in mourning. Going barefoot as a sign of mourning was universal.

The prohibitions on bodily mutilations were not always observed. The men who came from Shechem and Shiloh and Samaria mourning Gedaliah ben Ahikam (Jeremiah 41 :5) had ‘their beards shaved and their clothes torn, and their bodies gashed’. Many other forbidden customs were followed (see Jeremiah 16:6; 41:5; Amos 8:10; Micah 1:16).

Mourners showed their distress by refusing food. On the day of a burial none of the deceased’s relatives would eat. Nor at the end of day would they prepare food for themselves, but would be served by others who would also offer the ‘cup of consolation’.

After the death of Abner, all the people came to bring bread to the mourning David, but he would not eat until nightfall (II Samuel 3:35).

Funeral Lamentations

The dead would be wept and lamented over. Professional mourners and wailing women  would join the relatives (Amos 5:16; Jeremiah 9:17 ff; 11 Ch. 35:25) to make lamentation.

would join the relatives (Amos 5:16; Jeremiah 9:17 ff; 11 Ch. 35:25) to make lamentation.

A spontaneous lament could be amplified into a lament or ‘qinah’ – a poem composed in a special rhythm and sung by professionals, many of whom were women (Jeremiah 9:17-22).

Such women probably had a repertoire of laments which could be adapted to different occasions, but sometimes the poems were specially composed.

The most famous of these are the laments of David for Saul and Jonathan (II Samuel 1:17-27); and for Abner (II Samuel 3:33-34.

Mourning period – how long?

According to Mosaic law, one who dies must be buried on the same day. This applied equally to executed criminals (Dt. 21:22-3) and was obviously a wise provision in a hot eastern climate. The custom was perpetuated in post-Exilic times and a ‘halakhah‘ forbids keeping a corpse overnight.

In general the period of mourning after a death was seven days and during this period the mourners did not wash or anoint themselves (II Samuel 14:2).

Strange and brutal to us, but a man who wanted to take a captive woman for his wife had to let her mourn for her father and mother for a month in his house (Deuteronomy 21:11-13).

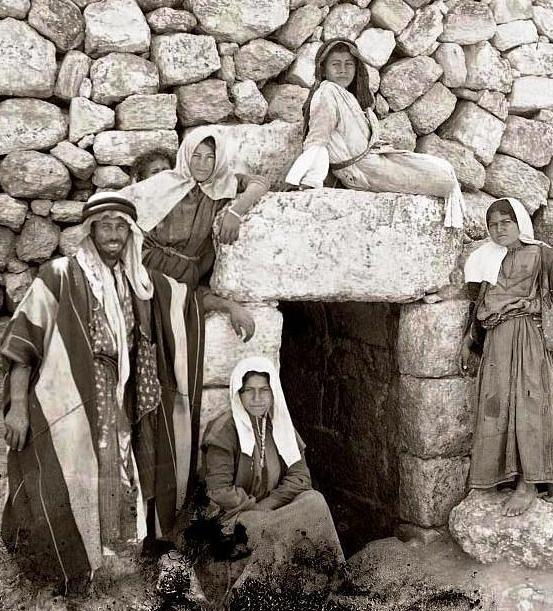

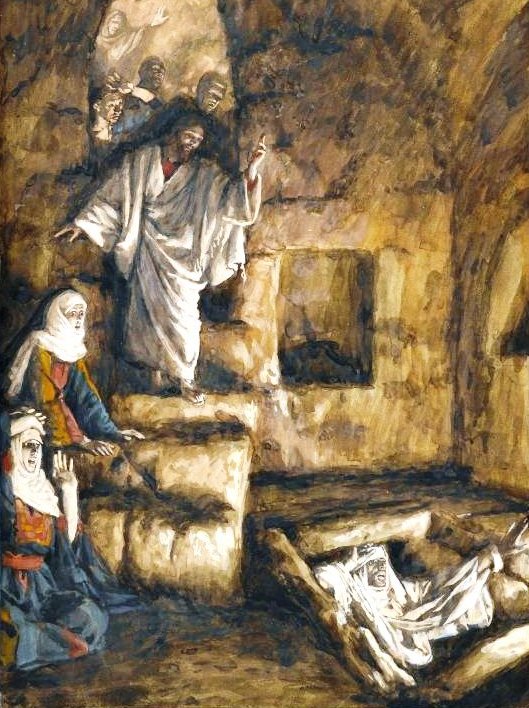

The Tomb of Lazarus

19th century photograph of the tomb said to have been for Lazarus

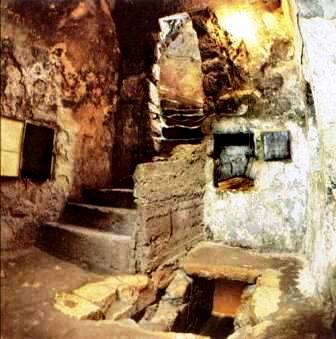

The Tomb of Lazarus today. If it really was Lazarus’ tomb, Jesus must have stood here when he summoned Lazarus from the tomb.

Inside the Tomb of Lazarus

James Tissot had obviously visited this tomb when he painted the scene above in his ‘Raising of Lazarus’- compare the actual tomb with his painting.

The Tomb of Zechariah, Kidron Valley

Some very fine post-Exilic tombs and monuments were found in the Kidron Valley, just to the south of Jerusalem’s walls. These include the ones known to tradition as the ‘tombs of Absalom, Zechariah and St. James’.

In fact the inscriptions prove that they were all the tombs of members of the aristocratic priestly family, the Bnei-Hezir, and they all belong to the 1st century BC.

Inscriptions show that these tombs belonged to members of the aristocratic priestly family, the Bnei-Hezir, from the 1st century BC – no earlier.

Once-magnificent tombs in the Kidron Valley, 1925 photograph

The Necropolis of Beth-Shearim

There is a vast Beth-Shearim necropolis near modern Haifa, which has served since the 3rd century AD as a large and elaborate burial centre for Jews from both Palestine and the Near East.

It is composed mainly of caves cut in the rock, each cave consisting usually of a large entrance corridor whence halls, burial chambers and single loculi branch out.

The most important catacombs have monumental arched masonry applied to the rock, with open-air places of prayer cut in the rock above them.

Entrance to the Tomb of the Sanhedrin: the origin of the name is unknown

There is another graveyard north of Jerusalem which was apparently used for the burial of ordinary people and had much simpler tombs than those of the Kidron Valley. The most elaborate of the graves are traditionally known as the “Graves of the Sanhedrin”.

The importance of burial

According to the Bible, it was absolutely essential that a person be given a proper burial. To deprive a person of this was the worst punishment. If the prophets wished to curse a king, they predicted that their bodies would be left out in the wilderness for wild animals to eat – ‘anyone who dies in the open country, the birds of the air shall eat; for the Lord has spoken’ (1 Kings 14:11).

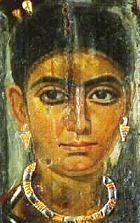

Fayum Coffin Portrait, Egypt 2-3rd century AD. Strict rules forbad Jews making images of a living creature. But in nearby Egypt coffins carried portraits of the dead – see the Fayum coffin portraits above. There is nothing like this in ancient Israel – even though many Jews lived in Egypt

In Israel, the proper way to be buried was in a family sepulchre, joining your ancestors in death. This applied to the highest and lowest in the land.

People felt they had an obligation to do this: when someone died far from home (as Jacob did, and Jesus) his relatives and friends saw it as their duty to bring the body home to the family sepulchre.

When the great forefather Jacob was dying, he told his son Joseph of Egypt to ‘carry me out of Egypt and bury me in the burial place with my ancerstors’.

Joseph, a good son, promised to do so (Genesis 47:30).

But according to the Law of Moses, a dead body or even a human bone were ritually unclean. If you touched it, you had to undergo ritual purification for seven days.

People were never buried inside the walls of the village or city. This was considered a pagan practice (see Jericho Skull). The only person exempted from this law was the King, who was buried in a royal sepulchre inside the walls of Jerusalem.

If a city wanted to expand its walls and build on land that had tombs on it, all the bones had to be exhumed and reburied outside the new city walls.

‘Whoever touches the dead body of anyone will be unclean for seven days. He must purify himself with the water on the third day and on the seventh day; then he will be clean.

But if he does not purify himself on the third and seventh days, he will not be clean.

Whoever touches the dead body of anyone and fails to purify himself defiles the Lord’s tabernacle. That person must be cut off from Israel. Because the water of cleansing has not been sprinkled on him, he is unclean; his uncleanness remains on him.

This is the law that applies when a person dies in a tent: anyone who enters the tent and anyone who is in it will be unclean for seven days, and every open container without a lid fastened on it will be unclean.

Anyone out in the open who touches someone who has been killed with a sword or someone who has died a natural death, or anyone who touches a human bone or a grave, will be unclean for seven days.’ Numbers 19:11-16

Bench burial caves

Tomb with rock benches: the Tomb of Kings, Jerusalem

The most common way to be buried was in a communal family tomb, in a cave hewn out of the rock. There were rock benches around the walls of each compartment, on which the body was placed.

When these spaces had all been used, and another body had to be buried, the bones on the benches were collected together and placed in the center of the cave – either on the floor or in a shallow pit dug out for this purpose.

Removing the bones in this way made it possible for one family to use the same tomb for many generations.

The Canaanites placed

- food vessels (and presumably food),

- personal objects such as jewelry,

- inscribed seals and

- weapons with the dead body.

This practice continued even as late as the 2nd or 1st century BC.

A circa 1900 photograph of a tomb which is said to have contained the body of the beautiful queen Mariamme, who was strangled by her husband King Herod the Great.

Upper Hinnom Valley, Jerusalem

Wall recesses

Up until the century before the birth of Jesus, the body of the dead person was placed on a stone bench in the sepulchre.

After this period, however, a new type of tomb was used. This was still carved into the rock, but now the benches were replaced by cavities cut into the side of the wall, one above the other – much the same as the catacombs.

Each of these cavities contained one body, which could be sealed in by a well-fitting slab of stone. The body would then be left undisturbed. This meant that people placing a new dead body in the tomb were spared the unpleasant sight of decomposing bodies from past burials.

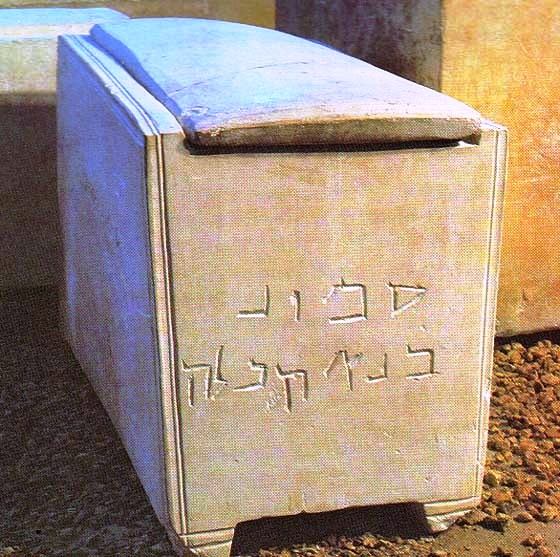

When the body had decomposed, the stone slab was removed and the bones collected. They were then placed in small individual stone boxes called ossuaries, which often had the name of the dead person carved on the side.

An ossuary was a box in which the bones of the dead person were stored.

This one was inscribed ‘Simon the temple-builder’

The entrance to this type of tomb was sealed with a large, heavy stone which had to be rolled into position. The entrance itself might be decorated with carvings and look out onto a small courtyard – according to the wealth of the family.

It was in this type of tomb that Jesus of Nazareth was buried on the night after his death on the cross.

‘So Joseph took the body and wrapped it in a clean linen cloth and laid it in his own new tomb, which he had hewn in the rock. He then rolled a great stone to the door of the tomb and went away. Mary Magdalene and the other Mary were there, sitting opposite the tomb.’ Matthew 27:59-61

Burial customs

When Jewish people heard that someone they loved had died, they tore the front part of their inner clothing. The tear was several inches long, a symbol of grief: it represented the tearing pain in their hearts.

It was the women’s task to prepare a dead body for burial. The body was washed, and hair and nails were cut. Then it was gently wiped with a mixture of spices and wrapped in linen strips of various sizes and widths. While this was happening, prayers from the Scriptures were chanted.

The body was wrapped in a shroud, but was otherwise uncovered.

Tombs were visited and watched for three days by family members and friends. On the third day after death, the body was examined. This was to make sure that the person was really dead, for accidental burial of someone still alive could happen.

At this stage the body would be treated by the women of the family with oils and perfumes. The women’s visits to the tombs of Jesus and Lazarus are connected with this ritual.

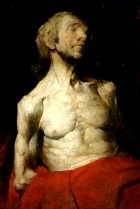

The Dead Christ, Mantegna

The ossuary

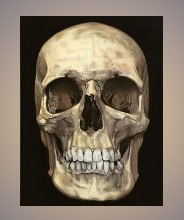

After visiting the tomb on the third day the body was left untouched for a year, by which time it had decomposed. The bones were then collected and stored in an ossuary, a ‘bone box’, with the large bones at the bottom and the smaller bones and skull placed on top.

Mourning the dead – how was this done?

- After the funeral, the family of the dead person stayed at home for seven days.

- They sat on the floor or on a low bench, barefoot.

- They did not wash themselves or their clothes, or do any work.

- They did not cook, but were given food by relatives.

- They were visited by a continual stream of friends and relatives, who sat with them and comforted them.

- For a thirty-day period after the death, the family members took no part in any entertainment, but lived a quiet, reflective life.

- After the death of a father or a mother, the mourning period was one year. This period was an opportunity to pay respect to the two people who had given you life.

Preparing the corpse for burial

Pins, fibulae and other ornaments discovered in excavated tombs in Palestine show that the dead were buried in their clothes.

- The description of Samuel rising from Sheol for instance (I Sam. 28:14) includes the fact that he was “wrapped in a robe“.

- b, with their weapons in their hands and their swords resting beneath their heads.

In Old and New Testament times, the dead were carried to the grave laid on a bier. Talmudic literature records that until the time of Rabbi Gamaliel (end of the 1st century AD) the people would bury their dead in luxurious garments involving considerable expense.

He ruled instead that the dead be buried swathed in white cloths and the custom has been maintained until today among the Jews.

According to the New Testament, a corpse was

- washed (Acts 9:37),

- anointed (Mark 16:1)

- wrapped in shrouds containing spices (John 19:40)

- the hands and feet were tied with bands and

- the face covered with a kerchief (John 20:7).

According to Matthew 27:59, Joseph of Arimathea took the body of Jesus and swathed it in a white shroud before burying it.

John 11 :44 describes the risen Lazarus appearing at the opening of his tomb ‘his hands and feet bound with bandages and his face wrapped with a cloth’.

Embalming, cremation

Embalming was never practiced in Israel. Jacob and Joseph were embalmed but in both cases it is ascribed explicitly to Egyptian custom (Genesis 50:2, 26).

There is evidence that corpses were cremated in Palestine long before the coming of the Israelites or, later, among groups of foreigners living in the country.

The Israelites themselves never practiced cremation which, like embalming, was considered sacrilegious and was forbidden by Mosaic Law (Leviticus 20:14; 21:9). I Samuel 31:12 records that the bones of the tragic King Saul and his son Jonathan were burned before burial by the people of Jabesh-Gilead but this was a departure from the usual custom. The parallel passage in I Chronicles (10:12) omits the burning and has Saul and his sons buried, not burned.

Incense, however, was burned at the side of the bodies of kings and other high dignitaries (Jeremiah 34:5; 11 Chronicles. 16:14).

Tombs

Pre-Israelite: A large number of Canaanite tombs from the Early to the Middle and Late Bronze Ages have been found throughout Palestine in many of the excavations of ancient towns. The most usual tomb was a natural cave or irregular, rounded chamber reached through a vertical shaft which could be sealed by a stone slab.

In this tomb at Megiddo, chambers lead off a vertical entrance shaft that can be sealed by a stone slab. Three chambers B, C and D open off a central chamber A.

Sometimes, in more elaborate constructions, the shaft had a flight of steps and the chambers were rectangular in shape. In general, burial grounds were outside a village or town.

The tombs of the Early Bronze Age (4th millenium BC) in Palestine were used successively for a number of burials and the custom was continued in the Middle Bronze. After each burial, the shaft would be filled, to be re-excavated the next time the tomb was needed.

When a new burial was to be made, the bodies and accompanying offerings from earlier burials would be pushed to the back and sides of the tomb chamber.

The final burial remained intact against a background of jumble from earlier interments, as shown in this picture (below) from a Jericho tomb (circa 1600-1700 BC). Many of the tombs probably belonged to a family group and contained twenty or so bodies, which would cover a few generations.

Group of bones in a Jericho tomb, circa 1600-1700BC. Reconstruction, Birmingham Museum

The bodies were laid side by side and, as can be seen from the Jericho tomb, a supply of food and equipment was placed beside them. This custom is found from the fourth millenium BC onwards.

The offerings apparently represented what was considered the necessary provision for the after-life and may equally well have been the equipment used by the dead in this life. Besides food and drink, aromatic oils and perfumes would also be placed in the tomb in clay pots and jars.

The Israelites continued the custom, although in a different form. Whereas the Canaanites used to supply their dead with food and drink, furniture and implements for use in the netherworld and on their way there, later Israelite graves rarely contain more than personal belongings and pottery containers.

Early Israelite Graves

No authentic tomb from the earliest Israelite times has ever been identified. Archaeologists interpret this as evidence that the majority of burial places of the common people must have been extremely modest — simple shallow graves which would easily be obliterated by time and tilling or erosion.

Ordinary people were probably buried in common burial pits, a ‘tomb of the sons of the people’ and the practice continued until the monarchy (II Kings 23:6; Jeremiah 26:23). More important burials were in caves or shelters under rocks. A few tombs of this kind have been found on the outskirts of Jerusalem.

According to Genesis,

- Sarah, princess of her tribe (Genesis 23:19)

- the great forefather Abraham, (25:9)

- the long-awaited son Isaac

- Rebecca the shrewd matriarch, and

- Leah, the unloved but fertile wife of Jacob (49:31) and

- the wily Jacob (50:13)

were all buried in the ‘Cave of Machpelah to the east of Mamre which Abraham bought … as a burying place’.

In general, people who died away from home were buried where they died.

Burial during the Monarchy

Family tombs continued to be used during the period of settlement and once the kingdom had been established.

- Gideon (Judges 8:32); Samson (Judges 16:31), Asahel (II Samuel 2:32) and Ahitophel (II Sam. 17:23) were all buried in ‘the tomb of their father’.

- The remains of Saul and Jonathan were finally laid to rest in Zela, in the tomb of Saul’s father, in their own tribal territory of Benjamin (II Sam. 21:14).

- It is mentioned that Samuel was buried ‘in his house at Ramah’ (I Samue; 25:1), and the same is recorded of Joab (I Kings 2:34), but this may mean a family sepulchre rather than a dwelling.

Except for the kings, there is no evidence that the dead were buried inside the towns. Tombs would be scattered over surrounding slopes, or grouped in places where the soil was suitable.

The normal tomb of the period of the monarchy was either a natural cave, or else a burial chamber cut out of the soft rock, made with an entrance opening, sometimes with a few steps.

The bodies were laid on ledges hewn out of the rock. When the chamber was filled, the bones were removed to niches in the walls of the chamber, so as to make room for new burials.

The tombs might be used by a family or a clan for a considerable time.

Diagram of burial caves found in a Samaritan excavation (explanation below)

The excavated tomb at Samaria

A typical group of tombs of thus period was discovered in the excavation of Samaria. The best preserved is an irregular cave measuring 5 m. by 4.70 (see plan above).

A rock pillar in the centre, which once supported the roof, has now collapsed.

An opening in the north wall led into a smaller chamber (2.4 x 1.9 metres and only 1.55 high) which must have been the burial place. It contained four skeletons, three adults, one child, laid with their heads to the east. Beside the bones were pots, beads of semi-precious stones, bronze and other objects.

Outside the chamber a kind of bench, 0.44 metres high, was cut in the rock.

In the floor of the cave were six holes, some with a double-rimmed mouth to carry a cover stone; two of them were connected by a narrow and shallow channel.

The holes opened into bottle-shaped rock-cut pits, varying in depth from 2.20 to 4.50 m. and in lower diameter from 1.80 to 2.90 m.

The pits were full of pottery, much of which had apparently been broken intentionally; there were also objects in bronze, iron, stone and bone, as well as some animal bones.

The pits suggest the practice of a cult of the dead, in spite of the rigorous opposition to it by the prophets.

In general, however, tombs of the Israelite period show few signs of burial offerings, beyond some pottery and clay lamps. Funeral offerings in the sense of provisions for the future use of the dead, such as the Canaanites had provided, are rarely found although there was a time when this custom was followed.

The entrance to a grave was carefully closed against robbers or beasts of prey.

Sometimes sepulchres of great splendour were prepared. Isaiah denounced a high official ‘Shebna, who is over the house’ for the magnificence of the tomb he had carved for himself (Isaiah 22:15-16).

When a funerary inscription from the period of the first Temple was discovered in the village of Siloam with an indecipherable name, it was very tempting to link it with the man Isaiah had in mind.

The inscription runs

“This is the sepulchre of …. iah who is over the house. There is no silver and no gold here, but only (his bones) and the bones of his handmaiden with him. Cursed is the man who will open this (sepulchre).”

Poor People’s Burials

Not every family could afford a tomb. A common grave or trench in which the bodies of homeless people or condemned criminals were thrown, was to be found in the Kidron valley near Jerusalem.

A more exalted offender, or a dead enemy, might have a cairn of stones raised over his grave.

Post-exilic burials

From the late Hellenistic period a new type of family sepulchre made its appearance. Instead of laying the bodies on ledges on three sides of the tomb, narrow perpendicular niches were cut into the walls and the bodies placed inside.

Alternatively, the bodies would be placed in a sarcophagus of limestone or lead. Later on the bones would be gathered together into stone coffers or ossuaries and the sepulchre made available for new occupants.

Part of a Roman-era lead sarcophagus,

which appears to show a menorah

Ossuaries – what were they?

The ossuaries might be made of wood, clay or lead. Stone ones were made in the form of houses with an arched roof, often decorated with rosettes of six, nine, twelve or more petals, or other plant and architectural motifs.

Others were left undecorated.

Many of them were inscribed in Hebrew, Aramaic or Greek with the names of the dead whose bones they contained. Over a thousand of these ossuaries have been found in Jerusalem alone, all of them dating between the 1st century BC and the 2nd century AD.

Tombs continued to be closed against marauding men or beasts. Sometimes this was done by a heavy stone door which could be locked. Other tombs were closed by means of a circular stone, as in this Herodian tomb (below) which could be rolled into position along a groove, propelled by a simple lever and kept in place by a small stone, called a dofek.

Tomb cut into the rock, with circular stone rolled away from the entrance. Photograph by Ferrell Jenkins

In general, until the late Hellenistic period, tombs were not distinguished by monuments. Rabbinic tradition (confirmed in Matthew 23:27-29) records that the doors were coated with chalk or whitewash as a warning to the passer-by to avoid the ritual defilement caused by inadvertent contact.

Mourning customs in other countries

The poetry of Ugarit contains descriptions of funeral and mourning rites and these are also referred to in various places in the Old Testament (e.g. Isaiah 15:2; Jeremiah 48:37.

One of the Ugaritic epics describes how the father of gods and his daughter, Anat, mourn the death of Baal. The god descends from his chair and sits on a stool, from there he descends to the earth, puts ashes on his head and earth on the crown of his head, covers his body with sackcloth, girdled at the waist, makes incisions in his flesh, clips his beard and pulls the hair out from his head.

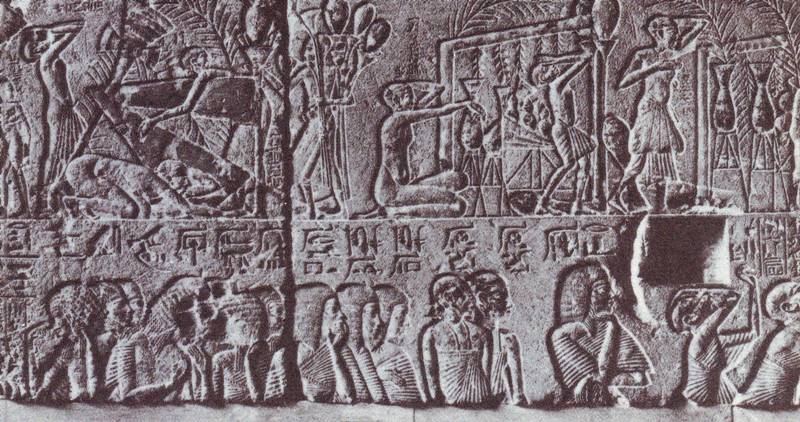

Archaeological discoveries have richly illustrated the mourning customs of other contemporary peoples.

Egyptian tombs, especially, contained a wealth of mourning scenes. Mourning women bared their breasts, covered their faces with earth, wrapped black and torn sacking around their hips, put ropes around their necks and raised their clasped hands above their heads (see wall relief below).

Egyptian tomb relief showing mourning practices (top panel) and the funeral procession (below). Notice particularly the woman in the top left corner.

The sarcophagus of King Ahiram of Byblos in Phoenicia

If you look at the sarcophagus of King Ahiram of Byblos in Phoenicia (above), you will see that one end has a carving of four bare-breasted women. Two of them have their hands over their heads and two are beating their sides. In front of the king stand men with their right arms bared.

This was a custom common to both Egypt and Palestine. Rabbinical literature refers to the baring of the arm and shoulder in mourning.

- Pre-Islamic Arab women bared their breasts and beat on them, tore their hair and their flesh and mourned for the dead for a week.

- The men would shave their heads and their faces, leaving the hair and beards on the tomb and offering sacrifices over them to the dead.

Hatshepsut’s necropolis at Thebes was everything the people of the Bible wanted to avoid when they buried their dead: over-the-top ostentation, and glorification of the dead rather than of God

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher