King David – the flawed hero

Who’s in King David’s story?

David, a self-made man of exception ability and charisma – brilliant but flawed. He is fascinating because he was not perfect, but always tried to do God’s will.

David, a self-made man of exception ability and charisma – brilliant but flawed. He is fascinating because he was not perfect, but always tried to do God’s will.

Samuel, an astute king-maker and adviser

Saul, the king David betrayed and replaced

Michal and Jonathan, the daughter and son of Saul; both of them loved David

Absalom, charismatic son of King David

Bathsheba, mother of David’s heir Solomon

David and Samuel

David is introduced to us in three different stories, as he faces three different men:

- Samuel, who becomes David’s chief adviser

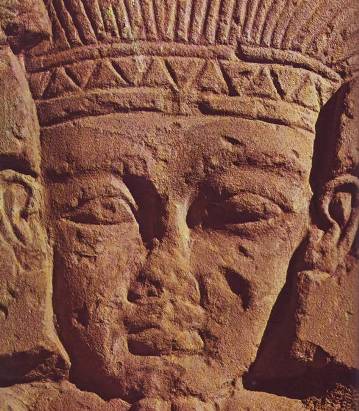

Face of a Philistine warrior, from an Egyptian wall carving

- Goliath, a Philistine giant and

- King Saul.

In the first story, a wise man and soothsayer called Samuel is looking for someone who will be God’s chosen one. He chooses David over all his older brothers – and naturally they do not like it.

David and Goliath

In the second story, David leaves the sheep he is tending and takes food supplies to his brothers in the battlefield.

He offers to fight the fearsome Philistine giant Goliath, and he defeats this ogre by cunning rather than physical strength, using a sling-shot.

You can see how to hold a sling in the picture at right. One end is attached to the middle finger; the thumb and pointer finder let go of the other end. This allows the slinger to let go of the cord at the right moment, sending a stone hurtling towards the target.

The story became popular because of the relative size of the two combatents: little David against the giant Goliath. But David may have had the advantage of Goliath all along – you can read Warfare – David and Goliath to see why. You can also read about David’s use of lateral thinking at Young People in the Bible

David & Goliath, Caravaggio

David and King Saul

In the third story, David charms King Saul with his music and poetry, and is accepted into the inner core of Saul’s court.

Each of the three stories is significant, because they show a different aspect of David:

- his ability to charm and engage the right people

- his use of cunning rather than traditional fighting methods – the Israelites were most successful in battle when they used guerrilla warfare

- his great personal charm, which he used without scruple all his life.

David replaces King Saul

David joined the court of Saul. He was adept at playing the harp, and Saul enjoyed his music. We know this was common at the time, from a a pre-Israelite plaque found at Megiddo (see at right, as a harpist plays for his prince much as David did for Saul (1 Samuel 18:10).

Court musicians had access to the king, and David made the most of it. But even while he seemed to sympathise with Saul’s problems, David constantly undermined the King.

Of course, Saul was no fool. He saw what was happening. He ruled by public acclamation, and now David was drawing the popular vote to himself.

Several times he tried to get rid of David, and in the end David was forced to flee. But not before he had formed close relationships with two of Saul’s children

- Jonathan, Saul’s trusted son and heir, and

- Michal, Saul’s younger daughter who fell passionately in love with David.

Saul Attacking David, Guercino

In an attempt to lessen the threat David posed, Saul let Michal marry David, but it did no good, and eventually Saul made an open attempt on David’s life.

David, helped by Michal, fled from the court, becoming an outlaw. Michal was left behind, and became increasingly bitter when David failed to send for her.

David then acquired two additional wives, shrewd Abigail and Ahinoam, and a considerable number of seasoned warriors. They formed an outlaw group moving from place to place and living by their wits.

He took this band of men and began fighting for his former enemies, the Philistines, but he did not actually take part in the battle in which Saul and all but one of his sons, including Jonathan, died. He did, however, send large gifts to the Israelite leaders as a conciliatory measure.

David becomes King

When David heard that Saul and his sons were dead, he went to Hebron. There he was anointed king by the men of Judah who had received his gifts.

One of Saul’s sons remained alive, Ishbosheth, but he was murdered in his bed by two of his retainers who brought the boy’s head to David.

David, now a king himself, sensibly killed the two retainers who had killed their king.

He also took Michal back from her second husband, even though she was most reluctant to leave him – and he to lose her.

David now launched himself on the task of uniting Israel and extending its territory – by alliance or warfare. He moved his capital to Jerusalem, since it was more central to the northern provinces he now included in his territory.

Jerusalem becomes David’s Holy City

He also brought the Ark from Hebron to Jerusalem, thus making his new capital a sacred city.

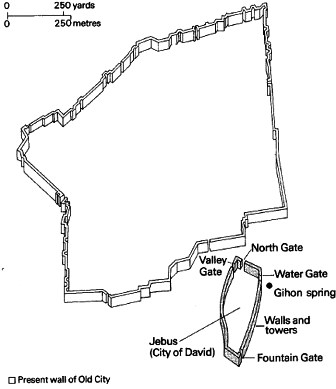

Jerusalem was a fortress rather than a city when David made it his capital

The map at right shows Jebus, the fortress David occupied, in the lower right.

In the procession leading the Ark into the city, a lightly-clad David pranced at the head of the procession so that his genitals were displayed. Michal, a princess from birth, was conscious of the need for royal dignity. She was contemptuous of his behavior and said so.

David was not pleased by this criticism. He no longer needed the royal status she had given him, so he relegated her, now an unnecessary thorn in his side, to perpetual chastity – and childlessness.

One of the first things that David did in Jerusalem was get an extended building program under way. He began to plan a suitable temple to house the Ark, and a palace for himself and his growing family.

David and Bathsheba

David began empire-building. He became engrossed in reform and administration, and no longer accompanied his military forces when they went into battle. Instead, he stayed in Jerusalem.

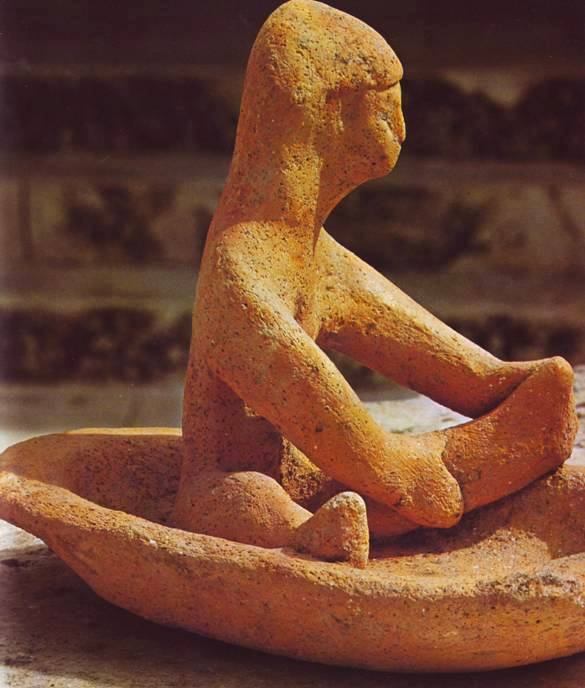

Woman bathing, clay statuette

from the time of King David

One evening when he was walking on the terrace of his palace he saw a woman bathing after her menstrual period, and sent for her. She came, they had sexual intercourse, and in due course she discovered she was pregnant.

Since she – the lovely Bathsheba – was already married this posed a problem, which David solved by organizing the death of her husband in battle.

She entered David’s harem, the baby was born, but she later gave birth to another son who would become King Solomon.

Absalom’s Revolt

David seems to have had little control over his children.

The heir apparent Ammon raped his half-sister Tamar and then refused to marry her – marriage would have been the normal procedure at that time, despite the fact that they were half-brother and sister.

Tamar’s brother Absalom bided his time, then murdered Ammon, and later led a revolt against his own father, David, but was killed in battle.

David’s family life is not far removed from Greek tragedy.

Succession to the Throne

When David was old his sexual potency failed him. This was a serious problem since people at that time believed that the potency of the king was linked to the well-being of the country.

A beautiful young woman was introduced, naked, into David’s bed, but it did not good.

Seeing his chance, David’s eldest remaining son Adonijah led an attempted coup d’etat against his father, to take power from the ailing old man. He was supported by his own brothers and by the general populace – the ‘people of the land’.

But Bathsheba had other ideas – she wanted the throne for her son. If Adonijah became king, her own son Solomon and his brothers would almost certainly be murdered.

She formed an alliance with various powerful groups in the country, religious and military, and replaced Adonijah with her son Solomon.

Soon after, David died – he ‘slept with his ancestors, and was buried in the city of David. The time that David reigned over Israel was forty years: seven years in Hebron, and thirty-three in Jerusalem’.

Jerusalem from the air. The area in the bottom right corner

corresponds to the fortress of Jebus, shown on the map further up the page

Tribal leaders rule? Or a king?

Note: The reign of David saw the beginning of a move from rule by autonomous tribal leaders to an organized kingship.

This was not popular with ordinary Jewish tribesmen, who believed they were being increasingly enslaved, subjects of a king rather than free men. H.D.Kitto in The Greeks writes about the Greek attitude to slavery, but it could just as well apply to the Israelites’ wary relationship with their kings:

Slavery and despotism are things that maim the soul, for, as Homer says, ‘Zeus takes away from a man half of his manhood if the day of enslavement lays hold of him’. The Oriental custom of obeisance struck the Greek as not ‘eleutheron’; in his eyes it was an affront to human dignity. Even to the gods the Greek prayed like a man, erect; though he knew as well as any the difference between the human and the divine. That he was not a god, he knew; but he was at least a man. He knew that the gods were quick to strike down without mercy the man who aped divinity, and that of all human qualities they most approved of modesty and reverence. (H.D.Kitto, The Greeks, p10)

Arbitrary government offended an Israelite to his core. It showed no respect for his person. Israel was surrounded by countries where law was arbitrary, expressing the private will of a king: palace government, not government according to a law derived from God. Acceptance of despotism like this would make an Israelite a slave.

Citizen’s rights emerged in Israel

before the birth of Greek democracy.

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher