Noah’s story explained

Flood stories are known in many other countries besides biblical Israel. There is, for example, a Greek story of a flood sent by Zeus to punish the sins of mankind, from which only the hero Deukalion and his wife are saved. There are also Babylonian and Mesopotamian stories of a Flood.

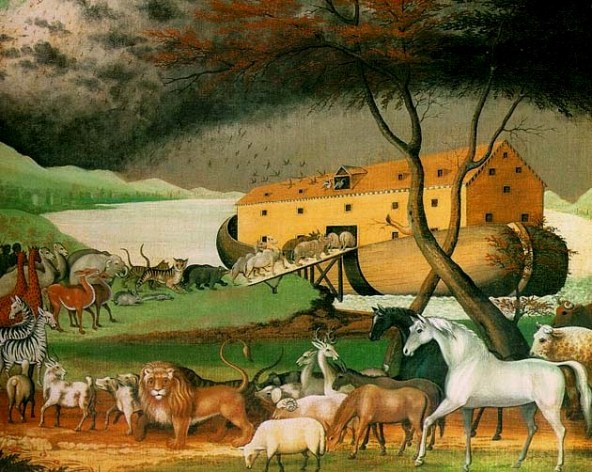

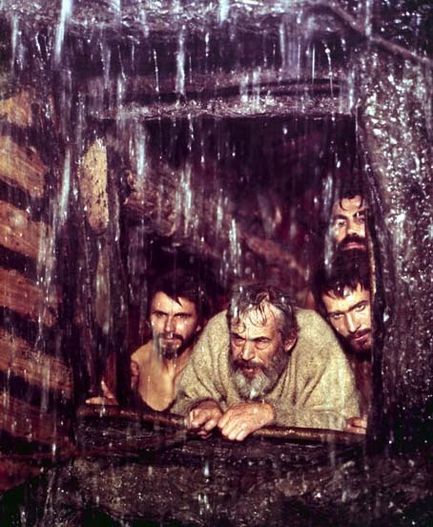

The Flood stories all have in common the destruction of the world and mankind, with the exception of one man and his family. In all of them, the man is ordered to build a vessel and to take his family and certain animals and plants with him in order to escape the universal devastation.

The Flood stories all have in common the destruction of the world and mankind, with the exception of one man and his family. In all of them, the man is ordered to build a vessel and to take his family and certain animals and plants with him in order to escape the universal devastation.

- The rains fall for a traditional number of days, 7 or 40.

- Birds are sent out of the vessel to signal the end of Flood – Utnapishtim sends out a dove, a swallow and a raven, Noah a raven and then a dove twice.

- The disappearance of the bird is a sign that the waters have abated.

- The hero goes forth from the vessel, offers a sacrifice and thereafter enjoys a special relationship to the gods.

- In the Sumerian epic he becomes a god.

- In the Babylonian he is granted eternal life “like unto us gods”, and of course

- God makes a covenant with Noah which is valid for all men and all time.

Evidence of Floods

Floods were common in Mesopotamia and layers of mud have been found at many ancient sites.

The most dramatic was found at Ur, where there was nearly three metres (about 10 feet) of mud at about the time of the composition of the Flood stories.

However in excavated mounds nearby, no traces of such a mud layer were found and in other sites where they did occur, they appeared at different levels, in different thicknesses, and did not belong to the same century.

Moreover, they do not always represent the complete destruction of a particular settlement and its replacement by a new one. Sometimes the same culture continues above the mud level showing that whatever damage may have been suffered, the population of the pre-Flood age was not wiped out.

No universal Flood?

The most reasonable conclusion seems to be that there was no universal Flood.

Localized Floods in the Mesopotamian plain, however, may have given rise to the stories which, with all their embellishments and exaggerations, became part of the religion and mythology of Babylon and spread their influence to the authors of the Bible.

A further possibility is that the origin of the story lay in traditions going back to the last great pluvial period in the Paeleolithic age. With successive movements of peoples these traditions were spread all over the world.

Other examples of the transformation of Mesopotamian motifs can be found in the legends of Genesis. The “Tower of Babel”, for instance, had its actual model in the Ziggurat, the high temple tower of Babylon.

Links between Babylonian and Bible stories

Opinions differ however, as to the way in which these Sumerian stories found their way into Hebrew lore. The majority opinion is now that the essentials of the story were brought to Palestine from Mesopotamia by the ancestors of the Hebrews.

There is also an alternative view that the theme reached the Hebrews from the Canaanites, who had already learned it from its original eastern creators.

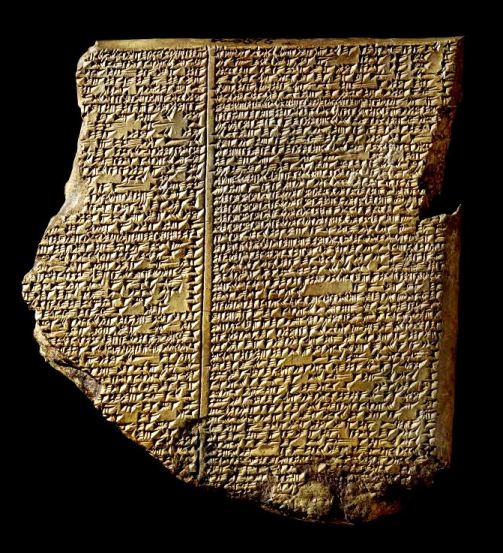

Tablet from excavations at Megiddo, with the Gilgamesh story

This theory has been strengthened by the discovery at Megiddo of a tablet (see above) from the period just before the Israelite entry into Canaan. This tablet contains part of the Gilgamesh story, which suggests that, by the time the Israelites came into contact with them during the settlement, the Canaanites were already familiar with Babylonian literature.

Contact between Hebrews and Canaanites was a long drawn-out process and far from exclusively war-like. Canaanite civilization, indeed, had a deep and lasting effect on Hebrew culture. Many scholars claim that the Megiddo tablet is powerful testimony for a Canaanite source for the Babylonian material in the Bible.

So what’s the conclusion?

It seems that the Flood story came originally from Mesopotamian epics and was integrated into a Hebrew or Canaanite epic about Noah, which was later interpreted, revised and written in prose.

The “documentary” school of biblical criticism has also advanced the theory that the story as it stands combines two strands or documents:

- the J (Jahwist) source, representing the popular epic, and

- the P (Priestly) document which provided the religious tone and theology of the present version.

This theory implies a priestly editor who, naturally, revised and rewrote the older story in keeping with his views. This would be the version we have in the Book of Genesis.

Search Box

![]()

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher