The Battle Axe – Bible Warfare

The battle axe was designed for hand-to-hand fighting. It was a fearsome weapon. There was very little defence against it. One swing and it could end your life, or at best maim you.

The battle axe was designed for hand-to-hand fighting. It was a fearsome weapon. There was very little defence against it. One swing and it could end your life, or at best maim you.

When you fought, you saw your enemy up close, and it was kill or be killed. So if you were facing someone with an axe, you had to be quick-witted, skilled – and preferably armed with an axe yourself.

What did the first battle axes look like?

A battle axe had a relatively short wooden handle, with a lethal head of either metal or stone. It was designed to be swung by the handle, with the head brought forcefully down on the enemy.

The purpose of the axe was to pierce and cut. It needed a sharp, light blade.

Design problems

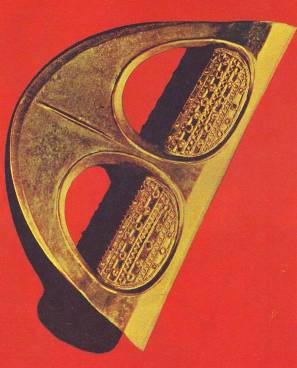

Ceremonial axe from Obelisks Temple, Byblos. Circa 1900BC

The key problem was fitting the head to the handle in such a way that it would not fly off when swung, or break off when struck.

To prevent the weapon from leaving the soldier’s hand when swung,

- the handle was widest at the point of grip, tapering toward the head

- or it was curved

- or sometimes both.

Since the axe was designed for hand-to-hand fighting, its development was guided by the need either to pierce or to cut. The quality of the enemy’s armor at the time dictated which of these was important.

What shape should an axe blade be?

This, too, influenced the form of the axeblade. The cutting axe was effective against an enemy who fought without armor. But if he wore armor, the piercing axe was required, with power of penetration.

Axes could therefore be broadly divided according to shape, which coincides with their function:

- the axe with a long blade ending in a short sharp edge was for piercing

- the axe with a short blade and a wide edge was for cutting.

The axe handle

It was also necessary to produce an axe that did not separate into two pieces when it was used. The blade had to be fitted to the handle in a way that it would not fly off in action.

This, of course, is a danger in all such instruments, even the axe used by the laborer. The Bible draws attention to it in Deuteronomy 19:5:

“And when a man goeth into the wood with his neighbor to hew wood, and his hand fetcheth a stroke with the axe to cut down the tree, and the head slippeth from the helve, and lighteth upon his neighbor, that he die. . . .”

The seven different battle axes

Axes are classified according to the way the blade is joined to the handle:

-

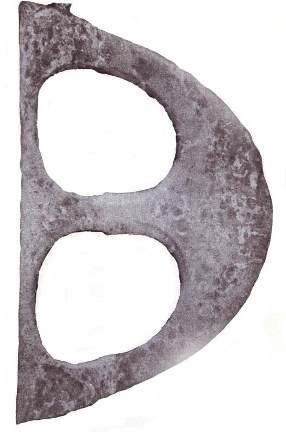

Duck-billed axe excavated at Ugarit

Duck-billed axe excavated at Ugaritthe socket type, in which the handle is fitted into a socket in the blade

- the tang type, in which the rear of the blade is fitted into the handle. In this type, the join was strengthened by binding or intertwining with cord.

- the epsilon axe, which gets its name because it is shaped like the figure 3, or the Greek letter epsilon. It has a short blade and wide edge, the rear of the blade having three projections or tangs by which it was fitted to the handle.

- the anchor axe, with a longer central tang projection from its rear fitted with a crossbar, by which it was fitted better to the handle. This projection and bar and the shape of the blade gave it the outline of an anchor.

- the eye axe, with two large holes in the blade.

- the duck-bill axe, (see right) with the longer blade and two smaller holes.

This variety reflects the way armorers tried to adapt to technical and tactical innovations, as they happened.

The Sumerians develop the Axe

Copper axehead circa 3100BC found as part of a cache of about 450 objects

One of the greatest technical achievements of the Sumerians was their development of an axe with a pipe-like socket, its blade narrow, long, and very sharp-edged (see an example of this socketed axehead, circa 3100BC, at right).

In doing this, they used already existing prototypes of such axes.

How do we know? Because of the dramatic discovery of a great number of copper axes in a cave in the Judean Desert, in the Dead Sea in Israel.

The appearance of this type of piercing axe among the Sumerians is no accident, for it is at this time and in this land that we find the first evidence of a high standard metal helmet (see Helmets).

Such helmets were useless when they met with a piercing axe swung with force.

Socketed axehead from Khafajah, early dynastic period

The Sumerian axeblade (see right) was made of copper. It was long and narrow, getting slightly wider and rounder near the edge. Its socket was rather like a smoking pipe set at an acute angle, so that the handle, which fitted into it, sloped forward.

To give a better grip and prevent its slipping out of the hand, the handle was slightly curved toward the bottom, where it was also thickened.

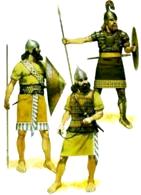

This axe was the personal weapon of the spear-carrying infantry and of the charioteers (see an example from the Standard of Ur, below).

Section of the Standard of Ur. Notice the axe carried by the warrior on the left.

The Sumerian axe continued to be used right into the Accadian period, particularly in Syria at the end of the third millennium, as we can see from the lethal axes discovered in the tomb of Til Barsip (see below).

Syrian socketed axeheads, end of third millennium

Right: crescent-shaped cutting axeblade excavated at Tell el-Hesi, 24th century BC. Spearhead at left.

The socket-type piercing axe spread from Mesopotamia to the area of Canaan, but did not reach Egypt. Egyptian armies always made do with the tang-type axe, primarily a cutting instrument, even during much later periods when they, too, had started using the piercing axe.

A good example of this kind of curved axe with a well-made central tang was found at Tell el-Hesi in Palestine (see right). An identical type was found in Jericho, together with pottery which was established as belonging to the Early Bronze III period (2600 to 2300 BC).

The Battle Axe in Egypt

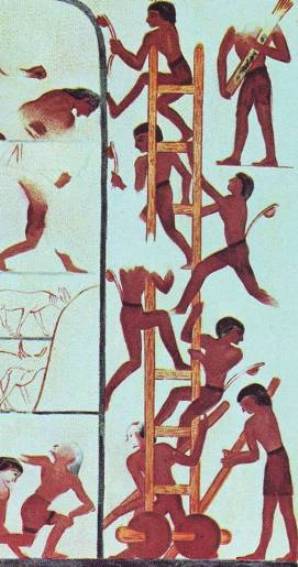

Egyptian soldiers with axes besieging a walled city and trying to scale the walls.

The ancient Egyptians seem to have rejected the socket-type axe. In the third millennium they were using wide-edged cutting weapons, and it was clearly difficult to fit such blades with a long socket. Moreover, it was fairly easy to attach the handle to the blade by means of a tang or by cords run through holes in the rear of the blade.

But this does not explain why, when the first piercing axe was finally introduced into Egypt in a much later period, it was socket-less.

Perhaps this was because the ancient Egyptians were notoriously conservative. They did not take to new ideas.

But it may be also that throughout the third millennium, Egypt had no need for a piercing axe. No helmets or coats of mail, against which a piercing weapon would have been needed, have been found from that period.

In the first half of the third millennium, the axeblades were mostly semicircular and often were fitted with lugs at the rear, on either side, to enable the handle to be bound more firmly.

Battle axes change in Egypt

Egyptian axe, late 3rd millennium BC

But starting from about 2500 BC we find the gradual introduction of the narrow blade, shaped like a slice of an orange. This was attached to a wooden handle by cords which were drawn through holes in its neck and fastened securely round lugs on either side.

The siege and battle scene shown on limestone in the tomb of Anta, at Deshashe in Upper Egypt is most instructive on the functioning of the axe in battle. It shows very clearly the shape of the “slice axe” used by Egyptian soldiers and it also shows how it was used: it was swung with both hands and brought smartly down to deliver a sharp blow.

In a scene from the wall painting at Saqqarah, you can clearly see the semicircular bladed axe. Here it was used mainly for tearing down the wall of a besieged city (see above right).

The Time of the Bible Patriarchs

Have a look at the flat, multi-tanged cutting axe that had been developed in the second half of the previous millennium (a tang is a metal projection on the blade of the axe, by which the blade is held firmly in the handle).

This sort of axe was most effective against an enemy not equipped with helmets – well, that goes without saying, really. It eventually fell out of use in the country of its invention. But Egypt, always reluctant to change, continued to use it – and they perfected it.

This was due, no doubt, to two factors:

- it conformed to the tradition of Egyptian axes, which were socketless

- it suited the pattern of warfare in Egypt during a time when their soldiers were fighting without armor, the warriors protecting themselves with a large body-shield.

Egyptian soldier carrying eye-socketed axe,

funerary temple of Mentuhotel II at Deir el-Bahri

The Egyptian epsilon axe (see above) was really a composite of two other styles:

- the short blade with the wide edge, which was already in use in Egypt,

- the triple-tang device of the Mesopotamian, Syrian, and Palestinian axe.

Epsilon battle axes, Middle Kingdom 20th century BC

In the latter type, the three tangs are wedged into the haft and made secure by binding; in the Egyptian axe, the tangs have holes through which they are fastened to the haft either by small nails or with cord, or by a combination of both, similar to their earlier method of attaching blade to haft. Some typical examples of this axe are shown at right and below.

Axes in the Bible lands

The axe was developing quite differently in Syria and Palestine. Axes showed the twin influence of tradition and necessity:

- traditionally, axes were the socket type

- but now the enemy had helmets and armor, against which the cutting axe was ineffective.

This led to the invention of a completely new type of axe: a piercing weapon with a socket.

The new axe is called the eye axe (see below) because of the prominence of its two holes, which look like hollow eyes. These are really a carry over of the spaces between the two inner curves of the epsilon tang – but they are now bounded at the rear by the socket.

The eye axe was a difficult weapon to produce. Some splendid examples of ceremonial axes of this type, made of gold, were found at Byblos; one is shown at the top of this page (see the image with a red background).

Eye-socketed blade, Egyptian,

Middle Kingdom

The eye axe was brought to Egypt by the Semites when they started to establish themselves there and even serve in the army. But it did not gain acceptance, no doubt because the tradition of the tang type was too entrenched. The Egyptians just did not like to change.

There are, however, some Egyptian examples of the tang axe being given an eye form.

The Syrian and Palestinian eye axe was improved by lengthening the blade and narrowing the edge.

- The hollows became smaller and less prominent, and the whole blade assumed the appearance of a duck’s bill – which is its name.

- The haft was usually curved to prevent it from slipping out of the hand, for the weapon required to be swung with much force.

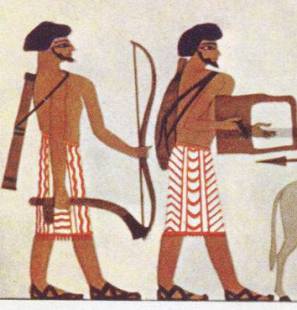

This is seen in the famous Beni-hasan wall painting of the caravan of Semites going down to Egypt, like the Israelites. The warrior on the left bears in his right hand an object which looks like an axe of this type.

Detail from the Beni-hasan mural showing soldier carrying an axe with a duck-billed blade

What’s the evidence?

In Baghouz, Syria, a cemetery was discovered belonging to this period which contained graves of warriors who had been buried with their weapons. These included duck-bill axes.

In the 18th century BC, the duck-bill axe had already given way to a new type which was designed solely for piercing and penetration.

This development was certainly prompted by advances in the development of armor. It demanded a very long blade with a narrow thin edge, almost like a chisel. This was a socket axe.

These weapons were so widely used during this period that there is hardly a warrior’s grave in Palestine and Syria in which they are not to be found.

Armies, and the craftsmen attached to them, never stopped trying to perfect their weapons and make them more dangerous for their enemies.

Egypt, Exodus, Joshua in Canaan

Some things never change. In this later period:

- the Egyptians continued to stick exclusively to the tang-type axe

- the other more flexible lands of the Bible used that weapon, but also the socket-type weapon.

Ceremonial axe showing King Ahmose overcoming his enemy, circa 1570BC

The story of one axe

One of the finest examples is shown in the image at right. It belongs to the end of the XVIIth and the beginning of the XVIIIth Dynasties, at the very outset of the New Kingdom.

It is the ceremonial axe of Queen Ahhotep, mother of two pharaohs, who received it as a present from her second son, Ahmose, the founder of the XVIIIth Dynasty, who completed the Hyksos expulsion started by his brother Kamose.

This beautiful axe has a long and narrow blade which curves to a wide edge and a wide rear. The rear portion has two lugs by which the blade, whose back is inserted into the wooden haft, is tightly bound to strengthen the join. The edge is very sharp and convex, which makes it an excellent piercing weapon.

This sort of axe was used throughout the period of the New Kingdom, though its shape underwent slight changes. Beginning from the 15th century, its blade becomes shorter and its edge narrower until eventually the edge becomes the narrowest part of the blade.

The end development can be seen in the axes in the hands of Tutankhaniun’s infantrymen shown on the painted lid of a wooden chest found in his tomb at Thebes, belonging to the middle of the 14th century, and those borne by the soldiers of Rameses II as illuminated in the relief from the temple of Karnak, belonging to the middle of the 13th century.

Bronze axe from Beth-shan, 14th century BC

But the most interesting and indeed the most beautiful group of axes from the other lands of the Bible in this period are of the socket type. One example is shown above.

The portion of the blade to the rear of the socket is fashioned into ornamental lugs, or prongs, in the shape of fingers of a hand, or an animal’s mane. This was not just decoration: both ends of the axe could be used to damage your enemy. A useful weapon indeed.

Battle axe links

__________

www.womeninthebible.net

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher