The Battering Ram

Imagine you are standing outside the walls of an ancient fortified city. Facing you are the gates. They are massive and firmly bolted. The walls around the city are thick, a mixture of stone and earthworks.

Imagine you are standing outside the walls of an ancient fortified city. Facing you are the gates. They are massive and firmly bolted. The walls around the city are thick, a mixture of stone and earthworks.

Inside these walls, you know, there is gold and silver for the taking, plus thousands of people you can sell into slavery. You are backed up by your own army and you know they can beat the defences of this city.

But how do you get inside the city?

There were six ways of getting inside a fortified city:

- climbing up and over the walls, mostly with ladders; this was virtual suicide for the men who attempted it

- breaking through the wall, using hammers and axes – again, suicidal

- digging under the foundations of the city wall, undermining the stone

- besieging the city: starving the inhabitants until they surrendered or died

- penetration by ruse, as was done in the Iliad with the Trojan Horse

- using a battering ram.

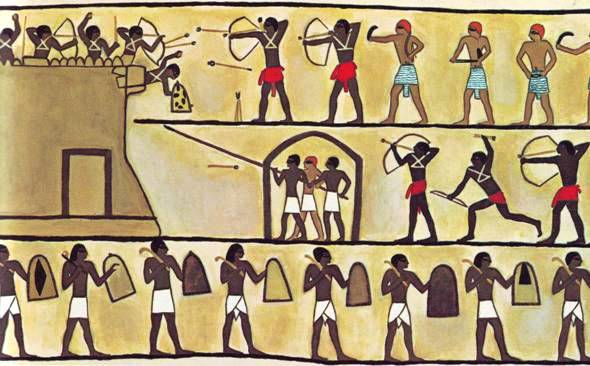

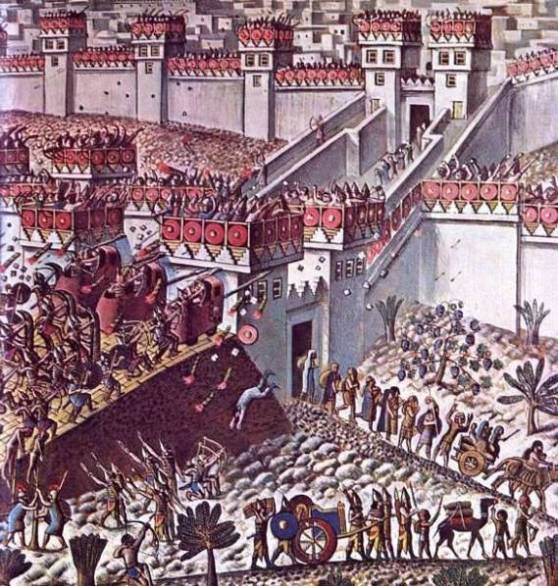

This wall painting from the Egyptian tomb of Khety shows a besieged city under attack. At the centre of the painting, three Egyptians inside an enclosed wicker shell thrust a long pole towards the upper part of the fortifications. Their aim is either to harm the defenders or weaken the wall.

The first, simple battering ram

In its earliest form, the battering-ram was simple: a long beam with a sharp metal head. It was thrust with force against the wall to be breached so that its head was lodged deeply between the stones or bricks. It would then be levered right and left, dislodging the stones of the wall and causing it to collapse.

In the era of King David and the Divided Kingdoms, it was probably a device with a hardened head, metal-capped, which was either swung in a harness secured to a fixed wooden scaffolding or by a group of very strong men charging a wall or gate.

What about the soldiers manning the ram?

In action, the soldiers handling the battering-ram had to reach the wall, bringing them close to the defenders above – and to their missiles. Unprotected, it would have been suicidal.

So to protect them, the battering beam was covered with a long wooden box-like structure, similar to the top half of a covered wagon. Its surface was strengthened with leather or shields, leaving the forward part open to allow the beam to be swung.

In later periods with more advanced engineering skills, this was adapted to give a better swing to the beam, to give it a more powerful thrust – the harder you could hit the gate or wall, the better.

In later periods with more advanced engineering skills, this was adapted to give a better swing to the beam, to give it a more powerful thrust – the harder you could hit the gate or wall, the better.

What the engineer/designer was trying to achieve was a kind of pendulum. It could be swung backward and forward, gathering momentum. When it was released, it would fly forward with great force and wedge itself firmly in the wall.

Essentially, a battering ram was the prototype of the modern tank or armored vehicle.

It was very heavy. This made things difficult, because it had to be moved from a distance (where it had been built or assembled) to the city under assault. Pity the poor draught animals that had to drag this load.

Once there, it had to be pushed right up to the walls by the soldiers themselves. So it was equipped with wheels, giving it the appearance of a covered wagon.

It was a tough task, for the ground was usually rough, rocky, and steep.

It was a tough task, for the ground was usually rough, rocky, and steep.

To make it easier, the assaulting force would lay an improvised track of earth strengthened with wooden planks, to serve as a smooth ramp up which the battering-ram could be moved to the city wall.

When it had been brought into position, it would be braked at the spot to prevent its rolling back.

Covering fire from the regular infantry was backed up by fire from special troops who would accompany the battering-ram, walking at its sides or even inside the structure.

Later on, the supporting troops took shelter in high, mobile, wooden towers from which they could fire at the defenders upon the walls.

The Mari Documents: what they tell us

The earliest illustrations of battering-rams are from the wall paintings of Beni-hasan dating back to the 20th century BC (see image at top of page).

To the right of the fortress is a mobile structure, rather like a hut with an arched roof. It served as cover for two or three soldiers whose hands grasp a very long beam with a sharp tip, probably made of metal. The point of the beam is aimed at the top of the fortress wall, to the people on the battlements. The lower part of the wall is protected by a low glacis, a sloping piece of land extending from the city wall.

This battering-ram, though it seems so primitive, must have been effective. Otherwise, it would not have been shown as the main weapon of an army attacking a fortress.

This battering-ram, though it seems so primitive, must have been effective. Otherwise, it would not have been shown as the main weapon of an army attacking a fortress.

Excavations at Buhen (see photograph at right) show that the magnificent fortifications were destroyed as a result of breaching by a battering-ram during the Hyksos period in the 17th century BC.

The documents of Mari on the Euphrates tell us more. The Mari letters (see one of these below) make several mentions of the battering-ram, made largely of wood, and of its effectiveness. Ishme-Dagan, for example, writes as follows:

“Thus saith Ishme-Dagan, thy brother! ‘After I conquered (the names of three cities), I turned and laid siege to Hurara. I set against it the siege towers and battering-rams and in seven days I vanquished it. Be pleased!’ ”

The power of the battering-ram must have been great, for in another letter, Ishme-Dagan reports that he conquered another city in a single day.

The power of the battering-ram must have been great, for in another letter, Ishme-Dagan reports that he conquered another city in a single day.

It must have been possible to move these heavy war machines over long distances, for another letter talks of transporting it by wagon and boat.

More detailed evidence of how the battering-ram was operated is contained in a Hittite document from Boghazkoy which describes the siege of a city named Urshu at the end of Middle Bronze II. The text reads:

“They broke the battering-ram. The King was enraged, and his face was grim: ‘They constantly bring me evil tidings. . . . Make a battering-ram in the Hurrian manner! and let it be brought into place. Make a “mountain” and let it [also] be set in its place. Hew a great battering-ram from the mountains of Hazzu and let it be brought into place. Begin to heap up earth. . . .’ The King was angered and said: ‘Watch the roads; observe who enters the city and who leaves the city. No one is to go out from the city to the enemy. . . .’ They answered: ‘We watch. Eighty chariots and eight armies surround the city.’ ”

Battering rams: the evidence

This document gives several details about the action of the battering-ram and its manufacture:

- The ‘mountain’ is nothing other than the mound or ramp of earth which had to be laid up to the wall, to fill in part of the moat, over which the battering-ram could be moved into position.

- The description also gives us information about the military units used to back up the battering rams: the chariots were there not for storming the city but to seal off the approach roads leading to the city, so that no ally could help the trapped citizens.

- The purpose of the siege towers referred to in the Mari documents was to enable the attacking archers to give covering fire from a greater height to the men operating the battering-ram, and to neutralize the weapons of the defenders upon the battlements.

- The importance of this covering fire by archers is endorsed in the Beni-hasan paintings, but here the mobile tower had not yet been introduced and the bows are fired from the standing or kneeling position from the ground.

All the evidence supports the view that the tremendous resources and effort invested in the fortifications of the Middle Bronze period were designed primarily to prevent breaching by the battering-ram.

This was the major purpose of the moat, the outer or advanced wall, and the glacis, which protected the steep slope and lower portion of the wall.

Battering rams change design of city walls

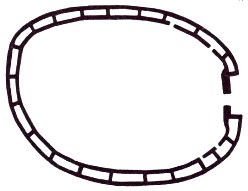

Casemate wall: relatively thin walls easily breached by a battering-ram

The changeover from a relatively weak casemate wall (like the one shown at right) to a massive wall of formidable strength could only have been caused by one thing: the enemy must have begun using a very powerful battering-ram.

And so it was. The Assyrian army had created a battering ram that made casemate walls useless.

From this time on, the casemate is abandoned in the construction of new city walls, and gradually disappears, being used in Iron Age II only for the walls of the inner citadel (as in the story of Rahab the prostitute of Jericho), or for isolated and independent fortresses, where the chambers of the casemates are used mainly for houses or storage.

The Assyrian battering-ram

They may have been effective war machines, but the mobility of battering-rams in the Assyrian army must have been somewhat limited. They were huge.

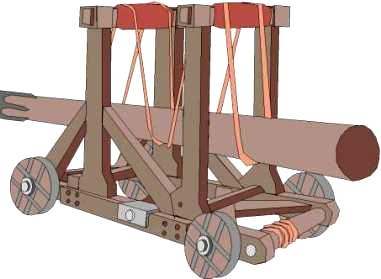

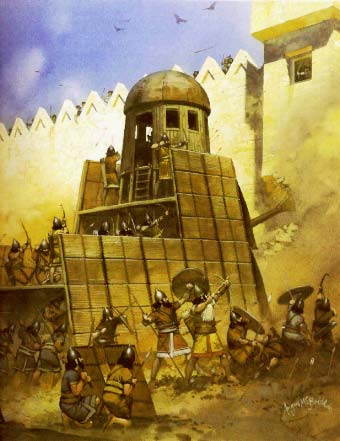

Reconstruction of an Assyrian battering-ram

One type moved on six wheels, its body built on a wooden frame, and its sides covered by a conglomeration of wicker shields common to the army of Ashurnasirpal (see a reconstruction at right).

From the size and number of the shields, we can calculate the measurements of the body of the battering-ram as between 4 and 6 meters in length and between 2 and 3 meters in height.

Its front was further heightened by a round domed turret (see the illustration at right and below). This may have been made of metal. Inside this turret hung the rope to which the battering beam was attached like a pendulum.

The turret also contained openings through which the crew could fire and, more importantly, could watch the walls and direct the operation of the battering-ram while they themselves were protected.

The turret itself was about 3 meters high, giving the front portion of the body an overall height of 5 to 6 meters from the ground.

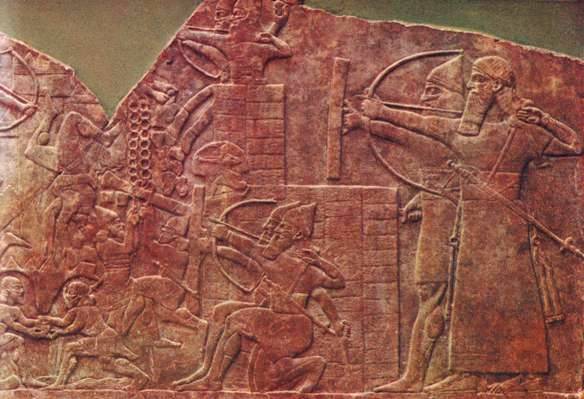

The wall relief of Ashurnasirpal clearly shows the separate parts of the six-wheeled battering ram: defending archers in the turret of the ram; the ram shattering the city’s stone wall; the compartment hiding the operators of the ram; and the wicker covering which protects soldiers within the ram.

How did the battering ram work?

The operational head of the ram was shaped like the blade of an axe. This would be inserted with force between the stones or bricks of the walls and, when it was in sufficiently deep, it would be levered to the right and to the left, displacing stone and brick and causing the collapse of a section of the wall.

To reduce the extreme danger to the warriors operating the battering-ram, who had to move right up to the foot of the wall and so offer a perfect target to the defending archers above, they were given covering fire by their own archers, who were perched on mobile towers.

These towers were possibly even higher than the battering-ram. The relief below depicts an even larger and heavier battering-ram which was almost certainly assembled near the city.

The artist in this relief adds a rare touch, portraying not only the method of operation of the instrument but also the action of the defenders. Note the chain to the left of the relief: this was dropped down so that it would loop around the ram, or tangle up in it, and so impede its capacity to destroy the wall.

Archers, battering ram, sappers undermining the city wall, chain tangling with the end of the battering ram, a falling body: all part of an Assyrian attack

But the Assyrian weapons had one great weakness. They were cumbersome. So Ashurnasirpal’s son, Shalmaneser, tried out a new type. It was more mobile, less heavy and awkward.

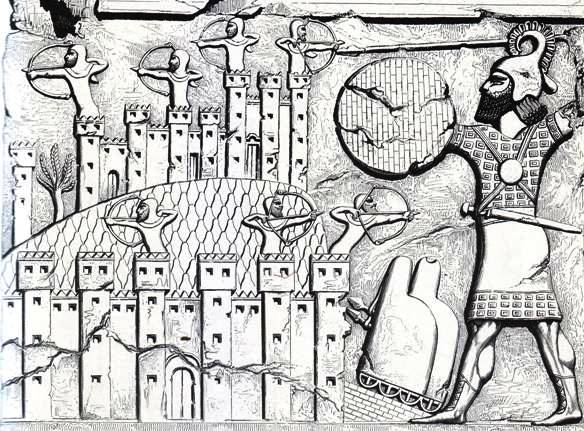

Six-wheeled battering ram attacking the city of Dabigu. The poles at the back of the ram may have been used by draft animals to drag the ram from place to place as required.

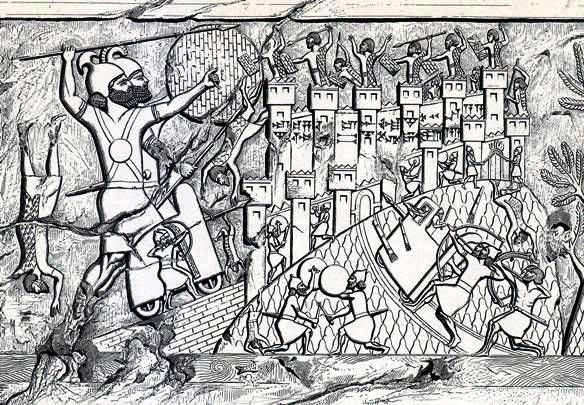

Four-wheeled battering ram attacking the city of Parga.

Two of these new types of battering-ram were depicted on the bronze gates of Balawat. Their characteristic feature was the snout, fashioned like the head of a wild boar, and they look rather like long wheelbarrows.

- The heavier type had six wheels (top), as in the reign of Ashurnasirpal;

- the lighter model (bottom) had four wheels, with six spokes like those of the chariots.

Their principal drawback was that their operational snout was so low that it could not be maneuvered into positions where it could reach the higher levels of the wall.

Battering rams: new models

Tiglath-pileser III owed much of his military success to a highly advanced type of battering-ram which he introduced into his army. In place of the cumbersome and rigid models, we now find light bodies on four wheels. These were easier to manoeuver.

In the illustration below, you can see what looks like a battering-ram with two poles or horns. This must show a pair of battering-rams – rather than a battering ram with two horns – operating side by side.

The wall relief at Sennacherib’s palace, a graphic record of the attack on Lachish, show seven rams working simultaneously.

This relief shows the siege, assault and destruction of a city by Tiglath-pileser III. The battlemented main wall of the city is no match for the battering rams (the two prongs suggest two battering-rams, one behind the other). The rams (centre) gouge into the wall, leaving the city open to the attackers.

Similar images appear on the reliefs of Sargon (see drawing below). Sargon’s battering-rams are essentially the same as those of Tiglath-pileser. He seems to be concentrating his force to the maximum by moving his battering rams to destroy a single point of the wall (below).

Sargon attacks a hapless city with at least two battering rams

Sennacherib introduced two improvements:

- he lengthened the ramming rod, and

- redesigned the body so that it was more easily assembled and dismantled.

Wall carving of Ashurbanipal

It is strange that no battering-ram appears on any of the reliefs of Ashurbanipal (see right), neither on those portraying operations against very distant fortified cities nor on those depicting action against cities near to his bases.

Battering rams in the Bible

Their absence is especially difficult to explain in the light of the fact that the Babylonian kings, who came soon after, certainly used them, as we see from the Biblical texts in the verses of the prophet Ezekiel:

“…And lay siege against it, and build a fort against it, and cast a mount against it; set the camp also against it, and set battering-rams against it round about” (4: 2).

Or

“At his right hand was the divination for Jerusalem, to appoint captains, to open the mouth in the slaughter, to lift up the voice with shouting, to appoint battering-rams against the gates, to cast a mount, and to build a fort” (21: 22).

These texts of Ezekiel aptly describe the method of operating the battering-rams, which are borne out in the Assyrian reliefs. The gate is chosen as the focal point of assault not only because it is the weak spot in the wall, but also because the battering-ram could then be wheeled up the path leading to the gate without requiring the construction of a special ramp (see illustration below).

Assyrian units attack the city of Pazashi

Ramps for battering rams

But such ramps were constructed on other occasions to overcome the natural steepness of the tel (the steep mound leading up to the city wall) when the chosen point of breach was a part of the wall.

These ramps were built up to have a top surface with bricks and stones (see above). Think of the extraordinary ramp built in later years by the Roman army at Masada.

Where the ramp was very wide, and designed to take a large number of battering-rams at the same time, only part of the surface was covered with wooden planks and bricks. These served as narrow courses for the individual rams and not as is represented in the reconstructed portrayal below.

A reconstruction of the siege of Lachish, with siege ramp and battering rams left centre.

Battering rams: links

__________

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher