What’s on this page?

Books about Queen Esther in the Bible.

What is her story?

What’s the point the Bible story is making?

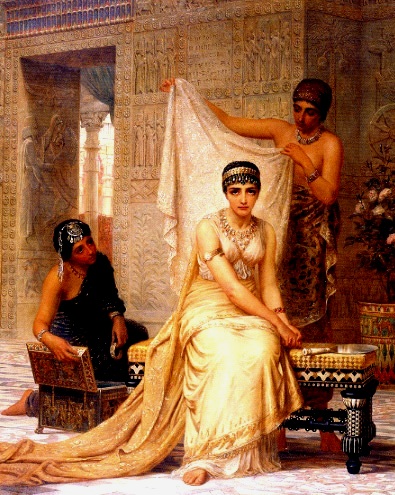

‘Not only does the queen (Esther) have the feminine charm of sexual attractiveness, but she also knows how to catch a man with food. To get the king into a receptive mood for rejecting Haman’s anti-Semitic pogrom, she invites Ahasuerus and his prime minister to a meal she will prepare.

She effectively deceives the manipulator, for Haman is unaware that Esther is Jewish, not to mention that she plans to have him killed. He brags to his wife and friends that only he and the king will be sharing the queen’s banquet.

Spider-like, she lures them to her quarters. Devoted to belly and other low satisfactions, the king offers to approve a large request from his queen after partaking of her tasty dishes. With feminine coyness, she merely invites the two men to a similar dinner the next day.’

Spider-like, she lures them to her quarters. Devoted to belly and other low satisfactions, the king offers to approve a large request from his queen after partaking of her tasty dishes. With feminine coyness, she merely invites the two men to a similar dinner the next day.’

___________________________

‘On the second day of feasting, the tipsy king rashly announces to his queen: “What is your request? Even to the half of my kingdom it shall be fulfilled.”

Esther vigorously asserts: “What I petition is that my own life and the lives of my people be spared. For we have been sold, I and my people, to be destroyed, massacred, and exterminated.”

A comic scene follows. When the king demands to know who has devised the genocidal plan, Esther exclaims: “A foe and enemy, this wicked Haman! ”

Haughty Haman then panics, and the angered king stomps out by himself into the palace garden. Then, ironically, Haman bows before a Jew to plead for his life.

On returning, King Ahasuerus sees that Haman has thrown himself on the couch where his wife had been reclining. Interpreting his posture as attempted rape, he orders Haman’s execution. He is strung up on the seventy- five foot gallows that had been prepared for Mordecai; the latter, who has earlier uncovered a conspiracy to assassinate the king, is given Haman’s position.’

Assertive Biblical Women, William E. Phipps, Greenwood Press, Connecticut, 1992, p.98, 99.

The Story of Vashti (1:1-22) The first female character the book of Esther introduces is Vashti the queen, the wife of Ahasuerus. Ahasuerus summons her to appear before his court in the midst of a wild drinking party, in order that he may show off her beauty. She refuses, and Ahasuerus, on the advice of his nobles, who fear that her example may cause other wives to rebel against their husbands, banishes her from court.

The author here introduces a touch of the burlesque; Vashti’s refusal to comply with the king’s demand is perceived by the men as a grave threat to the dominance of every husband in the kingdom. Ahasuerus and his courtiers appear as hapless buffoons before the calm strength of Vashti and, by implication, of all their wives!

The motive for her refusal is not given in the text, which has led to much speculation in the commentaries. For instance, the Targum [the Aramaic translation of the Hebrew Bible] in- forms the reader that the king wished Vashti to appear naked before the company and that out of modesty she refused.

Vashti serves mainly as a foil for Esther, although her character is in some ways more congenial to the modern woman. She is a strong female character who loses her position as a result of her refusal to acquiesce to the greater society’s demands upon her. It is ironic that her punishment gives her exactly what she wanted: she is no longer to appear before the king!

__________________________

….Esther is taken, with all the other virginal women in Susa, into the king’s harem. The text gives no judgment on the matter and seems to take her obedience to the king’s command for granted. To disobey would be suicidal. Verse 9 begins to portray Esther as more than merely beautiful. She earns the regard of Hegai, the king’s eunuch who gives Esther the best of everything in the harem. Esther, in other words, has taken steps to place herself in the best possible position within her situation.

Mordecai’s reaction to Haman’s plot is less than helpful to his own cause. He appears to go into a panic, putting on sackcloth and wailing in the king’s gate (4:1). Mordecai’s sole response to the crisis that he set in motion is to bring the problem to the attention of Esther. Esther now reappears in the story, responding to the report of Mordecai’s behavior by sending messengers to discover the cause of his actions. Mordecai responds by sending word to Esther of the disaster and charging her to go to the king.

Mordecai’s reaction to Haman’s plot is less than helpful to his own cause. He appears to go into a panic, putting on sackcloth and wailing in the king’s gate (4:1). Mordecai’s sole response to the crisis that he set in motion is to bring the problem to the attention of Esther. Esther now reappears in the story, responding to the report of Mordecai’s behavior by sending messengers to discover the cause of his actions. Mordecai responds by sending word to Esther of the disaster and charging her to go to the king.

This is the turning point of the story. Esther ceases to be the protégee of the male characters surrounding her and instead becomes the chief actor and controller of events.

In 4:11 Esther speaks directly for the first time in the narrative. All the king’s servants and the people of the king’s provinces know that if any man or woman goes to the king inside the inner court without being called, there is but one law—all alike are to be put to death. Only if the king holds out the golden scepter to someone, may that person live.

Esther’s reaction to Mordecai’s demand is not cowardice but a statement of fact. If she goes to the king unsummoned, the chances are good that she will die. In addition, what influence would she have with the king if he has not wished to see her in thirty days? Mordecai responds, however, by prodding her to act, emphasizing the importance of human action in accomplishing God’s purpose.

Women’s Bible Commentary, Carol A. Newsom & Sharon H. Ringe Eds., Westminster John Knox Press, Louisville,1998, p.134-5

Esther and Mordecai symbolize the powerless who vanquish their persecutors; Haman stands as the ultimate symbol of oppression. The story identifies him as belonging to the Agag family of the Amalekites—a desert tribe that harassed the Israelites at the time of the Exodus and later engaged in blood feuds with Saul and David. In time, “Amalek” and “Haman” alike came to mean anyone-—like Adolf Hitler—bent upon destruction of Jews. The feast of Purim probably originated as a secular Babylonian holiday, but the Book of Esther gives it a religious basis. Haman chooses the extermination date by pur – he casting of dice-like pebbles with designs carved or painted on them—and the word Purim is said to derive from pur.

Today, when the scroll of Esther is read for the feast, listeners cheer the heroes, Esther and Mordecai, and boo the villain, Haman. Children clatter noisemakers as well. Since Jewish law requires that every word of the scroll be heard, cantors must often pause for the noise to subside. Remembering centuries of terrifying pogroms, however, the rowdiness offers immense emotional release, and no one cares how long it takes to read the scroll. As a Yiddish proverb puts it, “So many Hamans and only one Purim.“

Today, when the scroll of Esther is read for the feast, listeners cheer the heroes, Esther and Mordecai, and boo the villain, Haman. Children clatter noisemakers as well. Since Jewish law requires that every word of the scroll be heard, cantors must often pause for the noise to subside. Remembering centuries of terrifying pogroms, however, the rowdiness offers immense emotional release, and no one cares how long it takes to read the scroll. As a Yiddish proverb puts it, “So many Hamans and only one Purim.“

Despite the emotional truth of the Book of Esther, the story itself is historical fiction. Except for King Ahasuerus (Xerxes I, 486-465 BCE), the characters appear in no other source, and even Ahasuerus was married to a different woman. Further, the ancient Persian empire consisted of 127 provinces that stretched westward from India to the Mediterranean and southward into Africa. Since all of these provinces were allowed their own religious practices, an empire-wide campaign against the Jews is highly unlikely. The story is probably based on a more localized act of oppression.

The book is nevertheless rich in historically accurate details.

- For example, eunuchs or castrated males, perceived as no threat to the king, were in great demand as royal guards and guardians of the king’s harems.

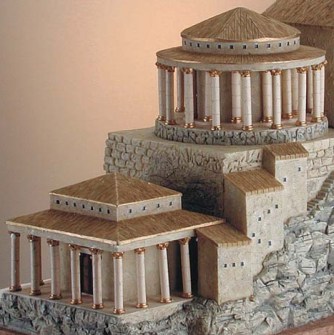

- The author was also familiar with the audience hall of the king’s winter capital at Susa or Shushan (on modern maps, in mid-Iran). The king sat in an inner throne room isolated, for security reasons, from the rest of the main hall. The hall was a richly decorated room 250 feet square.

- The author also knew the Persian bureaucracy so well he could satirize it. Legally, a king of Persia could issue a decree that affected the entire realm only after consulting his seven top officials. Such a decree could never be rescinded, though its effects might (rarely) be softened by a later edict. The author of the Book of Esther applies the cumbersome consultation process to a relatively trivial matter—the refusal of the king’s first wife to obey him – yet later depicts the king as allowing decrees of great importance to be issued with no consultation at all. The Book of Esther appears in different forms in Jewish, Catholic, and Protestant Bibles.

Like the small David overcoming the gigantic Goliath, Esther and Mordecai emerge as classic examples of “little people” who turn the tables on the powerful. Whatever the historical basis of the story, it celebrates deliverance of all who suffer persecution (or the threat of persecution) on the basis of race, religion, or gender. Achieving such deliverance, the book suggests, requires the taking of personal responsibility for one’s fate, not waiting for a miracle.

Their Stories, Our Stories, Rose Sallberg Kam, Continuum, New York, 1995, p.147.

…Though the book is thus at variance with known historical fact, it is claimed that it corresponds with certain mythological and cultic data.

- Haman and Vashti have been equated with the Elamite deities Human and Mashti, and

- the story is said to reflect their defeat by the Babylonian deities Marduk and Ishtar, represented by Mordecai and Esther.

- Again, the story has been explained in terms of the myth of the victory of Marduk (Mordecai) over chaos, in which, however, Ishtar does not play a prominent part.

It is probably a mistake to try to identify the characters with deities. The names are meant to indicate human beings; and the story is a story about men and women, not about gods and goddesses. But the explicit connexion of the book with Purim makes it reasonable to look for a cultic background. Unfortunately, the meaning of the word ‘Purim’, the origin of the festival, and the date at which it was introduced into Judaism are obscure.

A Critical Introduction to the Old Testament, G.W.Anderson, Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd, London, 1969, p.204.