Who was Herodias?

In paintings and movies, Herodias is always portrayed as an ugly, over-painted older woman with a lecherous husband.

Unfair. And untrue.

Herodias and Herod Antipas married for love, defying the people who pointed out that their marriage was incestuous.

She had been married to Antipas’ half brother and had a daughter with him, the princess Salome. But she ignored society’s condemnation and married Antipas anyway. A complicated family.

What sort of woman was Herodias?

Herodias seemed to be stronger than her husband Herod Antipas. She was a woman of action, but she had no direct power – a natural born mover and shaker denied the power to move or shake anything important.

Her husband was passive by nature. He could do what he wanted and did nothing, the sort of man who needs to be prodded into action.

Herodias had one great weakness: she was in love with her lazy, superstitious husband. They had a flaming love affair when both were married to someone else. They married, but they had to defy convention to do so.

She truly loved him – we know this because she stuck by him even when, later in life, he was deposed and exiled by the Roman emperor Caligula.

Herodias gives all for love

Agrippa II

‘Agrippa’s elevation (to favour with the newly crowned Emperor Caligula)proved Antipas’ downfall. Herodias could not bear to think that her scapegrace brother Agrippa should now be ruling as a king, while her husband, after forty-three years of service to Rome and to his people, was still only a tetrarch.

Antipas, now in his sixties, was content with his lot; but Herodias was fatally determined that he should improve it.

Antipas gave in, and in 39AD the two of them set off for Rome, in the most magnificent style.

Agrippa, who had of course been kept informed of the preparations, at first thought of going to Rome himself, but in the end decided to send ahead a confidential freedman, Fortunatus, with a letter instead.

Ancient statue in the now-underwater park

at ancient Baia, near Naples.

Fortunatus arrived hard on the heels of Antipas and Herodias, and was able to wait upon the emperor while Antipas was actually with him. This was at Baiae, the Brighton of ancient Rome, a thermal resort at the north-western extremity of the Bay of Naples, where many leading Roman families owned seaside villas.

Caligula had received Antipas kindly, but, as soon as he was told that a letter had arrived from his dear Agrippa, he interrupted the audience to read it.

Its contents were alarming. Agrippa accused Antipas,

- first, of having taken part in Sejanus’ plot against Tiberius;

- second, of being at that very moment in league with Artaban, the king of Parthia, against Rome.

As evidence of this last charge, Agrippa alleged that Antipas had in his armoury equipment for 70,000 men.

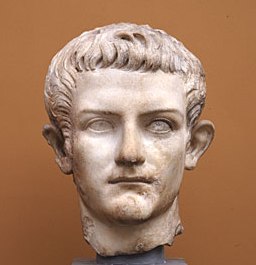

Bust of the Roman emperor Caligula

Caligula asked him whether this was true. Antipas was unable to deny it. There and then he was stripped of his tetrarchy, which together with all his fortune was given to Agrippa, and banished to Lugdunum Convenarum, which was not the modern Lyons, then an important mint and road centre, but Saint-Bertrand de Comminges, in Aquitaine, near the Spanish frontier.

Agrippa had now also arrived in Italy. When the emperor heard that Herodias was Agrippa’s sister, he said she might keep her own property, and offered her exemption from the decree of banishment.

Herodias replied that, having been the partner of her husband’s prosperity, she did not intend to forsake him in his misfortune.

Poor Herodias! For Antipas she had sacrificed her reputation; in an attempt to advance him she had ruined him, and enriched the rival she had thought to humble. Nevertheless she had been faithful to Antipas in her fashion, and preferred to remain so till the end.

Of Herodias, as of Shakespeare/s Cawdor, it may be said that ‘nothing in her life became her like the leaving it’.’

Quoted from The Later Herods: Political Background of the Gospels, Stewart Perowne, p.69-70

Search Box

![]()

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher