Bible Study Ideas

Discussion

Is it ever alright to kill?

What if…

- Your country is at war, and you believe this is a just war

- A person has committed a hideous crime and been sentenced to death

- You kill a person while defending yourself – you believed they meant to kill you

In any one of these situations, would you be justified in taking another person’s life?

Bullying

Bullying kills the spirit of the person being bullied, and in its own way is a kind of murder – see the sixth item at Top 10 Ways to Heaven.

- Where have you encountered it?

- Within your family? In the playground?

- At your work-place?

- Have you been guilty of it yourself?

- What can you do about it?

Discuss ways you can combat this ugly aspect of human nature.

____________________________________

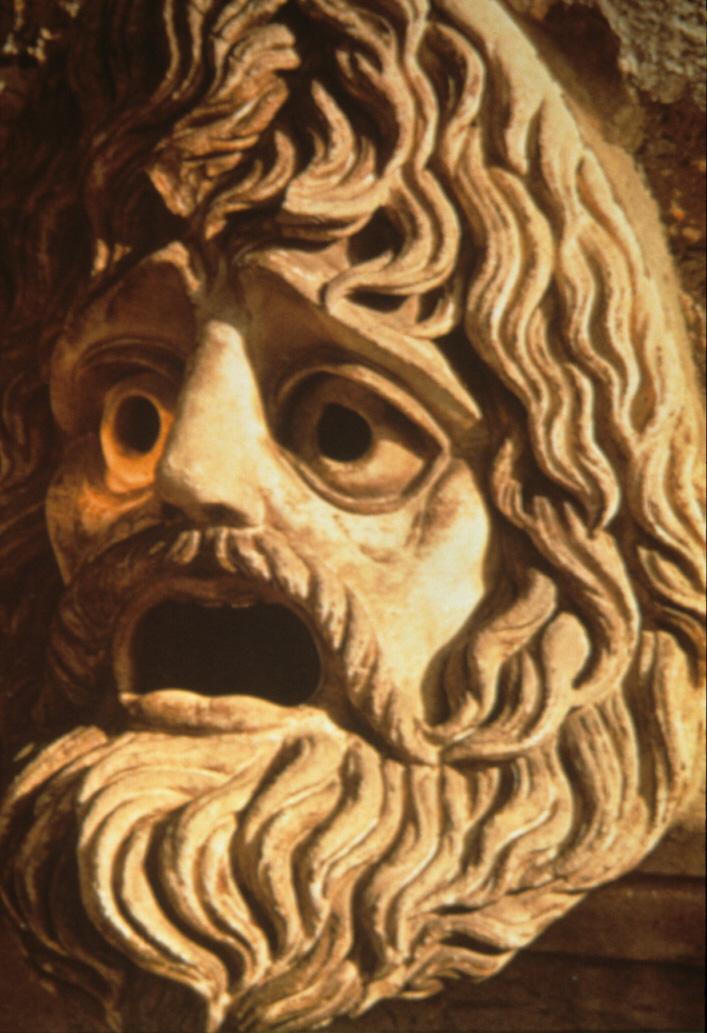

Name the movie

Can you name the movies?

Can you see a connection with Jephtah’s story?

Answers at MOVIE QUIZ ANSWERS (see ‘Jephtah’)

Can you think of others?

Movies with a tragic hero

Stage 1: Make up a list

List some films that deal with the fate of a tragic hero. You can choose recent films or classics. If this is a group activity, choose films most people know.

Stage 2: Glance over your list

1. Have you chosen films that are realistic, or do you prefer films that are inspiring?

2. Do your favorites have both these qualities?

3. What does this say about you and what you need in a story?

Stage 3: Choose your favorite

4. What are the central themes in this film?

5. Is the story dealt with in a realistic light?

6. Do any of the scenes remind you of your own life or experiences?

7. Or does the film express what you would like to have?

Stage 4: Think about your choices

Group activity: discuss these questions, making sure everyone in the group has a chance to talk about their ideas.

Single activity: sit down for a few minutes and focus your mind; make a quick list of your favorites; read through the Stage 3 questions, and think about them as you do other tasks in your day.

And on this subject…

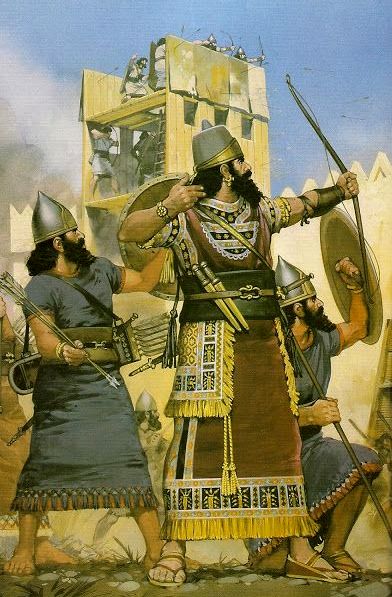

In the period of the Judges, Israel was usually outnumbered by enemy forces, and only equipped with inferior weapons.  Yet the warriors used their wits and the techniques of guerilla warfare to defeat superior armies.

Yet the warriors used their wits and the techniques of guerilla warfare to defeat superior armies.

Read about the techniques used by ancient Hebrew warriors at BIBLE TOP TEN WARRIORS.

Think about the techniques of guerilla warfare: you use the advantages you have and do not try to fight an enemy on their terms.

Read the story of David and the way he used lateral thinking when he faced Goliath – see BIBLE TOP TEN YOUNG PEOPLE: DAVID.

Now, with all that on board, think about ways you can apply this to your own problems. How can the techniques of guerilla warfare work in an everyday situation?

Focus Questions

1. What are the most interesting moments in Jephtah’s story?

2. In the story, who speaks and who listens? Who acts? Who gets what they want? If you were in the story, which person would you want to be friends with? Which person would you want to avoid?

3. What is God’s interaction with the main characters? What does this tell you about the narrator’s image of God? Do you agree with this image?

4. What is happening on either side of the story, in the chapters before and after it? Does this help you understand what is happening?

5. The narrator/editor has chosen to tell some things and leave other things out. What has been left out of the story that you would like to know?

6. Are the characteristics and actions of the people in the story still present in the world? How is the story relevant to modern life, especially your own?

Famous Quotes

‘Let the Lord, who is judge, decide….’ (Judges 11:27)

‘And she said to her father ‘Let this thing be done….’ (11.37)

- Are you able to hand over your life to God, to accept what you are given?

- Or do you worry and fret, trying to control things?

- Is it possible to strike a balance in your life?

Put some time aside to read the Bible text of this story, then think about the questions above.

Extra Reading

Extract from ‘Jephtah and His Vow’ by David Marcus, Texas Tech. Pr., 1986, pages 44-53

‘In every period of Israel’s history, marriage, not celibacy, is considered the desirable state for women. Indeed, it was considered a tragedy for a woman not to be married, and a terrible misfortune, even a punishment, if she did not have children.

The institution of the levirate marriage is clear evidence of the importance for a wife to bear sons for her husband and was what Israelite society considered the norm: that a man’s house and name should be continued in his children. In such a society, it is thought that it would be highly unlikely for a woman to take a vow to voluntarily refrain from marriage and from having children.

The non-sacrificialists do not disagree with this view of the primacy of marriage in Israelite society, but a few believe that it is possible to assume that some voluntary celibacy may have existed. This assumption is based on the fact that, according to Numbers 6:2, women as well as men could vow themselves to God as Nazarites.

Although the rules of the Nazarites, which specifically included abstinence from alcohol, not cutting the hair, and avoidance of corpses, did not include celibacy (the two most well-known Nazarites, Samuel and Samson, were both married), it is held most likely that this applied only to male Nazarites: they were permitted to marry, but a female one was not.

This is deduced from the fact that in ancient Israel a wife was considered the property of her husband. A woman consecrated to God would, therefore, regard God as her spiritual husband, and would become, so to speak, His property.

Hence, it would not be considered proper for such a woman to be married. She would remain in lifelong chastity or, in the case of a widow, in lifelong widowhood.

Summary: There is no real evidence in the Hebrew Bible of women’s electing to remain celibate, and the likelihood of this as a regular feature in society is remote. Likewise, there is little evidence in ancient Israel of an institution of celibate women being attached to a sanctuary akin to the chaste priestess in Mesopotamia, or to the vestals in ancient Greece and Rome in the cults of Athene, Artemis and Vesta.

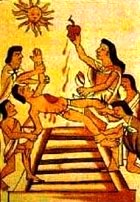

A RARE EXAMPLE OF HUMAN SACRIFICE IN ISRAEL

Most Bible scholars today believe that the story of Jephthah and his daughter represents an example of a human sacrifice offered up in emergency conditions to obtain the active cooperation of the deity.

Another example of this type is the sacrifice by Mesha, king of Moab, of his first-born son. Mesha, being invaded by the combined armies of Israel, Judah, and Edom, and seeing that the tide of battle was going against him, took his first-born son, and offered him up on the city wall as a burnt offering.

So he took his first-born son who was to succeed him as king, and offered him up on the wall as a burnt offering. A great wrath came upon Israel, so they withdrew from him and went back to [their own] land.

The efficacy of the offering was immediate. The deed caused tremendous consternation upon the allies, and especially upon the Israelites.

Thus, as with Mesha, it is believed that Jephthah was responding to an extraordinary situation, a desperate war with the Ammonites.

Even if one grants that the war with the Ammonites be considered “emergency conditions” or a “specially dangerous situation,” this view has, of course, to contend with an obvious and well-known problem. Given that human sacrifice was abhorrent to Israel, a vow to make a human sacrifice would surely have been against the law. This being so, one would expect some condemnation of Jephthah in the text after he put his daughter to death.

Attempted solutions to this problem by sacrificialists have generally followed two lines:

(1) it is held that a vow to offer human sacrifice was not in fact against the law in Jephthah’s time, or

(2) it is possible that Jephthah was unaware of the law.

HUMAN SACRIFICE NOT AGAINST THE LAW IN JEPHTAH’S TIME

In advocating that a vow to offer human sacrifice was not against the law in Jephthah’s time, a number of scholars point to the fact that the narrative does not seem to hold that such a vow is contrary to the spirit of Israelite religion.

Thus it is believed likely that in Jephthah’s time human sacrifice could have taken place. Religious beliefs of this age must not be judged, say the sacrificialists, according to later laws or ideas; even the later prophets were forced to wage war against child sacrifice. Soggin has recently pointed to the value of the Jephthah episode in enabling us to get a glimpse of early Israelite religion, telling us that it “had much more in common with that of Canaan and the other religions of the Ancient Near East than Israelites were able to record at a later stage or than the revisions of the text were disposed to admit”.

It has first to be established that human sacrifice existed in ancient Israel before one can assume that the Jephthah episode is an example of it, and hence that it represents an earlier stage of Israelite religion.

The fact is that it has never been satisfactorily established whether or not human sacrifice existed in Israel. The most recent studies on this old and difficult problem are those of Moshe Weinfeld and Morton Smith, who have debated the traditional view whether the reference to the passing of a child through fire or to Moloch indicates not child sacrifice but religious initiation to a foreign cult.

The present state of inquiry seems to be that the evidence is such that one cannot say for certain one way or another whether human sacrifice existed in ancient Israel.

JEPHTAH UNAWARE OF THE LAW

The second attempted solution to explain Jephthah’s action is that although a vow to offer human sacrifice was against the law, Jephthah was unaware of the law.

A reason often given, particularly by modern scholars, for Jephthah’s ignorance of the law is the fact that he lived outside of Israel for some time. Jephthah may have been, just as we know Israel was, influenced by the religion of the neighboring people.

The Book of Judges testifies to the fact that the Israelites worshipped the Ammonite god Milkom prior to their liberation by Jephthah; so it could well be that during Jephthah’s stay in the land of Tob as a freebooter or mercenary chief, he too came under the influence of foreign religion.

A basic element in this argument is the belief that the Ammonites, like others of Israel’s neighbors, regularly practiced human sacrifice in their cult. Thus, it is thought, Jephthah believed that just as other gods required human sacrifice, so did Yahweh.

The non-sacrificialists are able to refute this point of view in two ways.

- First, as the parallel case of David shows, the fact that one lives the life of a freebooter or mercenary outside of Israel does not necessarily mean that, upon one’s return, one cannot still live in accordance with the law of Israel. Having lived outside of Israel does not by itself point to ignorance of Israel’s law.

- Second, as with the case of Israel itself, there is no convincing evidence that human sacrifice was practiced as a regular part of the cult of any of Israel’s neighbors so that any alleged influence of this practice on Jephthah is most speculative.

NO CONDEMNATION OF JEPHTAH IN THE TEXT

The final question to be considered here, if in fact there is a case of human sacrifice, is why there is no word of disapproval or any moral evaluation in the text of Jephthah’s act.

- Jephthah is depicted in the entire chapter as a true follower of Yahweh (verse 9);

- he wages war on behalf of Yahweh, and calls upon Yahweh to judge between Israel and Ammon (verse 27);

- the spirit of Yahweh ‘comes upon him (verse 29), and he makes his vow to Yahweh (verse 30).

- He is extolled as one of Yahweh’s saviors in the Book of Samuel (1 Samuel 12:11), alongside Gideon, Bedan (possibly Barak or Samson), and Samuel himself.

Is it likely, then, say the non-sacrificialists, that Jephthah, a true Yahwist, would have presented an offering which was anathema to Yahweh, and that this fact would not be commented on by the narrator?

The usual answer to this question is that absence of condemnation has little significance.

- Firstly, it may point to the fact that human sacrifice was in fact current in Jephthah’s day.

- Secondly, even if this is not the case, there are other heroes in the Bible whose errant behavior is not condemned.

But if, as is generally agreed, the stories of Jephthah fit into the redactional framework of the Deuteronomist, then one would expect unlawful acts to be somehow condemned, either overtly or obliquely, in accord with the didactic outlook of the Deuteronomistic school. It will be recalled that the narrator castigated Gideon for a much lesser crime with the Ephod (Judges 8:27).

Absence of condemnation is therefore significant in judging a character’s action. Jephthah is not only not condemned but referred to by the same Deuteronomist as a “savior of Israel,” which is hardly an appellation to be applied to one guilty of such a crime.

SUMMARY

The proponents of the sacrificial point of view believe that Jephthah’s act is to be considered an example, like that of Mesha and his son, of human sacrifice offered up in an emergency.

To offset the objection that such a vow and execution would have been against the law, some proponents maintain that a vow to offer human sacrifice was not against the law, and if it was, Jephthah was unaware of it.

A possible reason offered for Jephthah’s ignorance of the law is that he had lived outside Israel and was subject to foreign influences.

The absence of condemnation of Jephthah by the narrator is pointed to by non-sacrificialists as proof that the vow and its fulfillment were not contrary to the laws of Yahweh in Jephthah’s time.

The sacrificialists, on the other hand, point to the absence of condemnation as proof that human sacrifice was acceptable in Jephthah’s time.

CONCLUSIONS

Perhaps the fate of Jephthah’s daughter is not the chief element of the story at all, rather Jephthah’s rash vow is. The story in effect is one which illustrates the consequences of a hasty vow; a fine irony for a man whose forte is seen to be eloquence of speech and mastery of words.

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher