What’s on this page?

Books about Miriam in the Bible.

What do they say about Moses’ sister, who saved his life?

What new ideas can you find here?

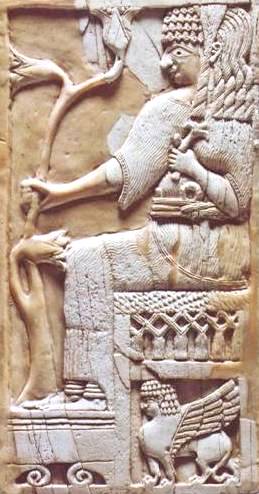

According to the Bible, two women, apart from his mother, assist in saving the infant Moses from a cruel Egyptian edict. Pharaoh’s daughter finds the papyrus basket that Jochebed has left for her to discover when she comes to bathe in the Nile. On opening the basket, she takes pity on the crying baby, who is identified as a Hebrew. His ethnicity is probably evident by his circumcision, since the operation was not performed on Egyptian males until puberty.

Flouting her father’s decree that Hebrew infants be thrown into the Nile, Pharaoh’s daughter has him drawn out of that river. She names him Mosheh, meaning “drawn out” in Hebrew, to commemorate how he became known to her.

Jochebed’s daughter, presumably Miriam, is also part of the mother’s shrewd plan for saving a baby who can no longer be hidden from the Egyptian police. Miriam is left to watch over her younger brother and negotiate for his safety.

Jochebed’s daughter, presumably Miriam, is also part of the mother’s shrewd plan for saving a baby who can no longer be hidden from the Egyptian police. Miriam is left to watch over her younger brother and negotiate for his safety.

After the Egyptian princess discovers and appreciates the baby she presumes is abandoned, Miriam approaches to provide help. Her offer to find a slave wet nurse to care for the child is accepted, so Miriam fetches her mother. Ironically, the princess arranges for the child’s nurture without realizing that she is actually dealing with the baby ’s mother.

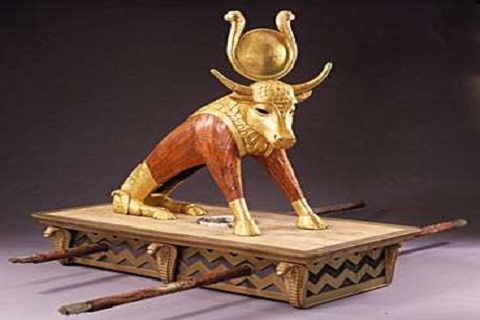

Miriam has a subsequent significant role in the exodus from Egypt, even though the editors of the Pentateuch have successfully minimized her position. After Pharaoh’s chariots become mired in the Sea of Reeds in pursuit of the escaping Israelites, she officiates at a victory celebration.

The following vignette commemorates the Hebrews’ relief at the vanquishing of what appeared to be an overwhelming military power: The prophet Miriam, Aaron’s sister, took a tambourine and all the women followed her, dancing to the rhythm of tambourines. Miriam led them in this refrain: Sing to Yahweh who has triumphed gloriously; Horse and rider he has thrown into the sea.

The exuberant body movements here described were probably of Egyptian origin; tomb art of the same dynastic period as the Israelite exodus certainly shows women dancing with tambourines and castanets. Women musicians had high status in Egyptian worship, and presumably this was also the case among the early Israelites.

When Miriam directs women in jubilant song and dance to commemorate deliverance, she thus begins a tradition that the Israelites occasionally repeat after other battles.

Scholars have recognized Miriam’s song as one of the oldest compositions in the Bible, dating back to the second millennium before the Christian era. Since the song is one of praise to Yahweh, Miriam should be acknowledged as the first Israelite psalmist. What she began became her culture’s greatest contribution to the arts.

Assertive Biblical Women, William E. Phipps, Greenwood Press, Connecticut, 1992, p.33-34.

For Moses, the books of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy unreel a saga. For the women in his life, Exodus and Numbers offer snapshots: ‘

- In a palace courtyard stand two Egyptian midwives, blithely concocting lies about their active role in saving the lives of Hebrew baby boys.

- Among the reeds on a lush river bank crouches a competent little girl, guarding the cranky baby her mother has set afloat in a papyrus basket.

- On the same bank stands a princess, adorned in gold and clothed in fine white linen, handing over the care of her newly claimed son to his own mother. ‘

- A bloody knife flashes in the firelight as another woman rescues her husband from a deadly night-terror.

- Cymbals sparkle in the sun as Miriam the Prophet leads ten thousand Israelites in song and dance.

- Miriam’s skin erupts with disease, and shock registers on the faces of her people.

Jochebed, the mother of Moses, never speaks. But her actions display her determination to do everything within her power before entrusting her son to others. With her husband’s tacit approval, she conceals the baby, perhaps among the clay pots of a storeroom.

Jochebed, the mother of Moses, never speaks. But her actions display her determination to do everything within her power before entrusting her son to others. With her husband’s tacit approval, she conceals the baby, perhaps among the clay pots of a storeroom.

When the baby becomes too active for concealment, she weaves a tiny ark from stems of the papyrus, a water plant said to repel even crocodiles. She waterproofs her ark, much as Noah sealed his, and sets her son adrift in it. But she posts as sentinel the watchful Miriam, a stalwart ally even at age seven.

Jochebed and Miriam must already know the bathing habits of Pharaoh’s daughter, and something of her character, too, for young Miriam shows no surprise when the Egyptian woman takes pity on the occupant of the tiny ark. One can easily imagine the princess guessing the identity of the conveniently available wet-nurse and relishing the ironies: she proposes to pay Moses’ mother to care for her own child until he is about seven, and then to feed, clothe, and educate the boy royally – all at the expense of the very man who has demanded the boy’s death….

And finally there is the adult Miriam who leads her people in ecstatic song and dance, giving focus to their dream of freedom. Like her brothers she speaks for Yahweh—until the day she and Aaron condemn Moses’ marriage.

In the story of Miriam’s and Aaron’s complaining, the fact that Miriam’s name comes first and that only she is punished suggests either the degree of power Miriam held, or the desire of the later editor to denigrate a woman.

To their credit, both brothers protest Yahweh’s harshness, and surely Miriam recognizes the injustice of a punishment inflicted on her alone. As she wanders in loneliness outside the camp, however, her brothers’ devotion and awareness of her own importance to her people must provide cold comfort. A century ago, suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton…. tartly opines that if Miriam had been in charge, the Israelites would have reached Canaan in forty days instead of forty years.

Tradition holds that when Miriam dies in a place where no water is available, the people nevertheless remain encamped for thirty days in order properly to solemnize her death.

Their Stories, Our Stories, Rose Sallberg Kam, Continuum, New York, 1995, p.82-3.