‘Given changes in attitude toward prostitution, it is little wonder that rabbis of late Old Testament times and the early centuries of the Common Era struggled with the story of Rahab. Some argued that because the text does not specify that Rahab has sex with Joshua’s spies, she was really only an innkeeper—a profession suspect only of dishonest trade.

In contrast, other rabbinic commentators chose to magnify her profligacy in order to enhance the wholeheartedness of her conversion to Israel.

In contrast, other rabbinic commentators chose to magnify her profligacy in order to enhance the wholeheartedness of her conversion to Israel.

Some even made her a prophet in her own right, the ancestor of nine prophets (including the renowned Jeremiah and the female prophet Huldah), and the wife of Joshua himself—a man revered as a second Moses.’

______________________

While the source of Rahab’s income cannot be resolved, it is clear that she possessed keen intelligence and leadership ability. Perhaps, like Miriam, she was an older sister to whom her siblings naturally turned for advice or a helping hand. Clearly, too, she was industrious; she stored flax on the flat roof of her house in order later to weave linen from it.

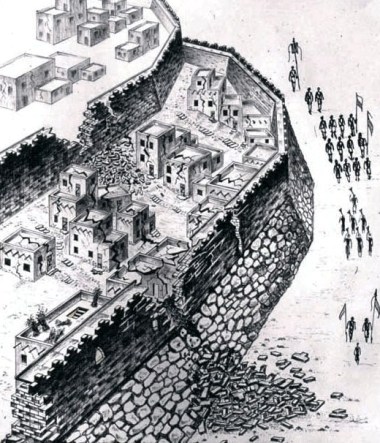

Her house seems to have enjoyed a well-protected location. It may have been situated between two walls, as in the fifteen—foot gap archaeologists found between the double walls of ancient Jericho. In addition, its position near the city gates would have made it possible for the politically astute Rahab to catch from customers and passers-by the winds of fear that preceded the Israelites.

_____________________

Rahab’s choice—to risk all on the power of Yahweh and the dependability of Yahweh’s agents—implies shrewd insight and a leap of faith. She emerges, too, as a woman of nerve.

Today, Rahab can serve as model to women living in all war-torn places, including inner cities. Such women, in order to create oases of life in the midst of violence, must balance one danger against another. They must decide whether to trust in the promises of police and social workers, or the protection of violence-prone gangs. They must discern whether to stay with an abusive but known male partner, or to risk life without a masculine protector.

They must listen with silent savvy, yet ultimately act as their conscience dictates.

Their Stories, Our Stories, Rose Sallberg Kam, Continuum New York, 1995, pp.87-90

Israel’s problem with foreigners has a decidedly sexual dimension. Foreign women are targeted as the problem, easily seducing Israelite men into worshipping other gods. The lure of such women manifests itself in the story of the spies at Jericho.

The spies are sent forth from Shittim—where Israelite men, to their detriment, first get involved with foreign women (Numbers 25). From this inauspicious starting place, the spies go directly to a brothel and “they lay there.” The verb “lie” is loaded with sexual overtones, and the context suggests that the spies are not above mixing business with pleasure.

The spies are sent forth from Shittim—where Israelite men, to their detriment, first get involved with foreign women (Numbers 25). From this inauspicious starting place, the spies go directly to a brothel and “they lay there.” The verb “lie” is loaded with sexual overtones, and the context suggests that the spies are not above mixing business with pleasure.

The common argument that a brothel would have been the best place to secure information about the city only accents the fact that the spies neither ask questions nor eavesdrop on any conversations.

From Israel’s perspective Madame Rahab is the epitome of the outsider. She is a woman, a prostitute, and a foreigner. As a prostitute she is marginal even in her own culture, and her marginality is symbolized by her dwelling in the city wall, in the very boundary between the inside and the outside.

Yet it is Rahab who understands best the nature of Yahweh. “Yahweh your God is indeed God in heaven above and on earth below”. And it is Rahab who saves the lives of the feeble Israelite spies, who willingly cavort with foreigners, indeed with a woman whom they would have eventually slaughtered in combat.

Rahab’s faith and kindness raise serious questions about the obsession with holy war in the book of Joshua. How many Rahabs are killed in the attempt to conquer the land? How many people with vision and loyalty surpassing that of the Israelites are destroyed in the attempt to establish a pure and unadulterated nation?

Women’s Bible Commentary, Carol Newsom & Sharon Ringe Eds., John Knox Press, Louisville, 1998, p.72