The Bible’s Flood story – true?

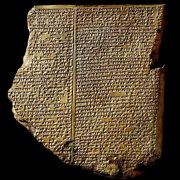

The Assyrian Flood Tablet

Assyrian tablet inscribed with part of the Babylonian story paralleling the biblical account of Noah’s Ark c.650 BC from the palace of Ashurbanipal, Nineveh (northern Iraq)

Of all the thousands of tablets discovered in the libraries of the Assyrian kings at Nineveh, none caused such a sensation as the Flood Tablet. The story of its rediscovery by an intrepid young assistant in the British Museum is an extraordinary tale of luck and adventure.

Who was George Smith?

George Smith’s Assyriological career began when an official at the British Museum noticed his intense interest in the sculptures from the excavations of the Assyrian capitals. He was given a junior position and set to finding joins among the 20,000 fragmentary cuneiform texts from Ashurbanipal’s library (mostly copies of older Babylonian and Sumerian works) discovered at Nineveh in the 1840’s and 1850’s.

One day in 1872, as Smith later described, he came across a curious tablet which had evidently contained originally six columns . . .

“On looking down the third column, my eye caught the statement that

- the ship rested on the mountains of Nizir, followed by

- the account of the sending forth of the dove, and

- its finding no resting-place and returning.

I saw at once that I had here discovered a portion at least of the Chaldean [Babylonian] account of the Deluge.”

A Babylonian Noah!

Smith, a rather nervous and excitable character, could not contain himself. ‘l am the first man to read that after more than two thousand years of oblivion’, he exclaimed. Then, ‘setting the tablet on the table, he jumped up and rushed out of the room in a great state of excitement and, to the astonishment of those present, began to undress himself’.

Public reaction to Smith’s sensational discovery was hardly less dramatic. The scholarly community and the public alike were captivated by the thought of biblical history coming graphically to life through the records of the ancient Assyrians. The London Daily Telegraph offered 1,000 guineas to fund an expedition to find the missing portion of the story. Smith eagerly accepted and headed off to Nineveh in January 1873.

Smith puts the pieces together

With incredible luck, after only a week’s work, he found a fragment from another tablet bearing most of the missing section of the story among the debris from the previous diggings (such was the carelessness of the early excavators).

But the story has a tragic end. Returning from Nineveh through Syria after an abortive expedition three years later, Smith succumbed to dysentery and died in Aleppo at the early age of thirty-six.

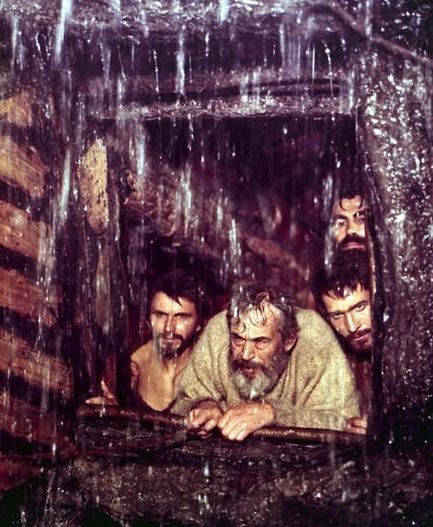

The Noah of the Babylonian flood story turned out to be called Utnapishtim (meaning ‘l have found eternal life’), who tells his tale to the legendary hero Gilgamesh. Distraught at the death of his great friend Enkidu and obsessed with the thought of his own mortality, Gilgamesh seeks out Utnapishtim to learn how he has been able to avoid the fate of all other mortals.

Utnapishtim duly explains how Enlil, the lord of the gods, had been disturbed by mankind and sent a devastating flood to decimate the world.

The ‘great boat’: the Ark

But Ea, the god of wisdom, took pity on the pious Utnapishtim who, like his biblical counterpart, was instructed how to build a great boat into which he brought ‘all the living beings’ — ‘the beasts of the field’ and ‘the wild creatures of the field’ — as well as all his family and craftsmen.

At the end of the story, after ‘all of mankind had returned to clay’ and the waters had receded, the dutiful Utnapishtim offered sacrifices to the gods. Pacified by his piety, Enlil took Utnapishtim and his wife aboard the ship and made them kneel, touching their foreheads as he blessed them: ‘Hitherto Utnapishtim has been but human. Henceforth Utnapishtim and his wife shall be like unto us gods’.

Thus was the godly man admitted to the realm of the immortals.

What’s the evidence for the Flood?

A half-century after Smith’s discovery, it was found that an early section of the Sumerian King List, preserved on clay tablets, interrupts the monotonous recitation of dynasties and rulers with the statement: ‘(Then) the Flood swept over (the earth)’. Here, it seemed, was historical proof of this catastrophic event, and some archaeologists were tempted to look for evidence of a great deluge in Sumerian sites.

A half-century after Smith’s discovery, it was found that an early section of the Sumerian King List, preserved on clay tablets, interrupts the monotonous recitation of dynasties and rulers with the statement: ‘(Then) the Flood swept over (the earth)’. Here, it seemed, was historical proof of this catastrophic event, and some archaeologists were tempted to look for evidence of a great deluge in Sumerian sites.

And indeed they soon found it: thick layers of water-borne silt sandwiched between the remains of successive settlement. One such deposit was found at Shuruppak, Utnapishtim’s home town, dating to about 2800BC.

But silt layers occurred at other sites at different dates; the thickest of all (over three metres) devastated Ur over 1000 years earlier. Indeed, flooding was a recurrent danger in Sumer and there seem to have been a number of catastrophic inundations affecting various settlements from time to time.

But there is so far no evidence of a flood which affected all of Sumer, nor any definite link between any of the flood levels that have been found and the deluge of Babylonian literature.

From an archaeological point of view, the flood remains unproven, and many now explain the story as a literary creation, though one which drew on widespread experience of this common phenomenon.

Search Box

![]()

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher