Paintings of angels

God’s messengers

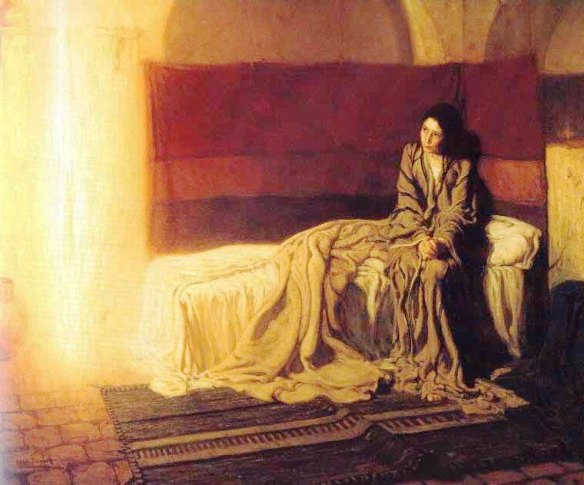

Henry Ossawa Tanner, Annunciation, 1898

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Annunciation, 1898

Look at this painting, then contrast it with the angel-painting by Petrus Christus below. Same subject, same positioning of figures, same story – but completely different presentation.

Does this help us understand the 19th (Tanner) and 15th (Petrus Christus) centuries? There are differences in taste certainly, but also differences in attitudes and images of the Divine. Tanner breaks away from the traditional picture of a winged creature, and presents the Angel as light, pure energy – and therefore as Revelation.

He invites the viewer to ask what it was that Mary saw and experienced. If it was an angel, what is that exactly? A compelling idea? A dream? A moment of blinding clarity? And do we ourselves ever have visits from an angel?

Bible Reference: Gospel of Luke 1:26-38

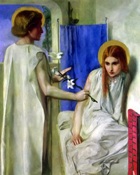

Petrus Christus, The Annunciation

Petrus Christus, The Annunciation

Petrus Christus’ paintings are at once sumptuous and ordinary: extraordinary events in an everyday setting, something for which Dutch painters were famous.

The room in which the Virgin sits is spotlessly clean, scrupulously neat, full of fresh air, and yet simple – very Northern European. She would fit right in in the Netherlands…

Notice in particular the angel’s wings, splendid as a Bird of Paradise from the exotic jungle of New Guinea – very un-North European. In contrast, the tiny dove representing the Holy Spirit hovering above Mary, is pure white. The Holy Spirit has no need of brilliant color.

Petrus Christus settled in the city of Bruges in 1444 and purchased his freedom of that city, becoming a master in the Guild of St Luke. He may have been a pupil of Jan van Eyck. He was certainly influenced by that artist. Van Eyck’s Annunciation angel has more sumptuous clothing, and Mary lives in a more up-market house, but the style is very similar, I think you’ll agree.

Bible Reference: Gospel of Luke 1:26-38

Embroidery as Art: the Syon Cope

A section of the Syon Cope – a richly embroidered vestment for a priest or bishop, made in England in about 1310-20.

Medieval English churches were richly decorated. Wall paintings, vestments, windows, carvings, statues – everything in a church reflected the beauty of God.

All this went in the Reformation.

Pre-Reformation vestments were savagely destroyed by the reformers. This remnant (above) was probably saved by being spirited out to a European country before it could be burnt.

The angel is the Archangel Michael, triumphing over the rebellious archangel Lucifer – here depicted as a two-headed Devil.

Angel, Giotto’s Madonna & Child

This lush angel is only a small detail in a painting of the Madonna and Child in the church of San Georgio alla Costa in Florence. You hardly notice it behind the much larger figure of Mary.

It’s astonishing then that Giotto has lavished so much care on this beautiful face. Every strand of curling hair, every shadow on the face, shows Giotto’s comsummate skill.

Notice the calm on the face of the upper angel, and the fixed gaze of the second face. Both of these beautiful creatures radiate devotion to the Madonna.

John Collier, Annunciation

John Collier, The Annunciation

And now for something completely different. In this extraordinary modern painting, Mary is a suburban schoolgirl who finds herself in an improbable situation. In her sports shoes and smock, she is greeted by a reverent Archangel Gabriel. He knows who she is and what she will be, even if she does not.

The angel does not seem to have spoken yet. Only its rapt gaze at the lilies, symbols of virginity, give the viewer a clue that something momentous is about to happen.

The artist, John Collier, jolts the viewer by making the scene immediate, now, not thousands of years ago. A Virgin with untied shoelaces and scraped-back hair? Surely not. Yet the painting has more dynamism than the work of many, more traditional, artists.

There is one little reference to the piety of the Middle Ages: Mary is reading a book. Medieval scholars suggested that Mary was no ordinary peasant girl: she had been selected to serve in the Temple of Jerusalem, where she studied among other things the Book of Isaiah. That is why you’ll see her reading or holding a book.

Bible Reference: Gospel of Luke 1:26-38

Caravaggio, Rest on the flight into Egypt

Caravaggio, Rest on the Flight into Egypt

What a daredevil Caravaggio was. You can see why he shocked people. The Christian churches in Europe were at the zenith of their power, but Caravaggio painted a Madonna dressed in red (the colour associated with loose-living women) and slumped over in exhausted sleep (the Madonna was usually serene and goddess-like, needing no food or sleep).

And what about Caravaggio’s Joseph, patiently holding sheets of music for a violin-playing angel? Where did that come from?

Or an angel with the grey-black and slightly sinister wings of an eagle?

But what an angel! Its gold-hued flesh and the loose cloth tied around its body are radiant with glowing light. The sheen of its wings catches the dying light. This really is a heavenly creature.

Bible Reference: Matthew 2:13-15

Bernini, Ecstasy of St Teresa of Avila

Bernini, The Ecstasy of St Teresa of Avila.

Everyone comments on the open mouth and languid body of St Teresa – her ecstasy looks decidedly sexual.

The truth is that Bernini had such skill, such originality and verve that he threw away the idea of mere representation and tried instead for something more: a way of expressing different levels of the divine, the mystical and the earthly.

This he does in the Ecstasy of Saint Teresa. The saint’s body seems to float in space, having lost its earthly weight. She is transported into another physical and emotional realm, the world of the Divine.

Look at the angel – no solemn figure here. A mischievous smile lights up his face as he prepares to plunge the arrow into her heart.

Leonardo da Vinci,

detail from Madonna of the Rocks

Leonardo da Vinci, detail from Madonna of the Rocks.

The sweetness of this face, the calm beauty, almost outshines the main subject of the paintings, which is of course the Madonna.

A light shines onto the face from above – God’s light. This face has never known sin or grief.

The angel gently supports the figure of Jesus, who raises his hand to bless the other child in the painting, the infant John the Baptist. Surely this is one of the most serene and beautiful faces ever painted.

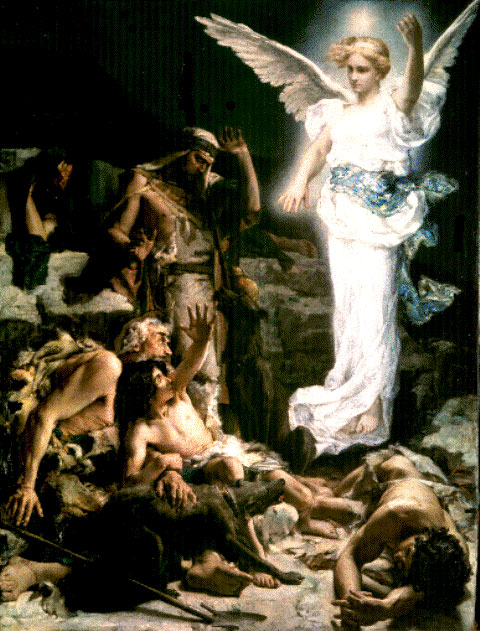

Leon Francois Comerre

L’annonce aux bergers, 1875

Leon Francois Comerre, L’annonce aux bergers, 1875

The shepherds are bathed in a luminous light from the angel, so much so that one of them tries to shield his eyes from the glare. He has recognised that this creature is from the realm of the Divine, and shields his eyes accordingly.

The angel hovers above them, suspended, an arm raised either in greeting or command. One man has fainted outright, as well he might.

A rather scruffy mountain dog seems undecided whether to attack or retreat. Sensible dog.

Perhaps the most arresting aspect of this painting is the contrast between the black night sky and the scruffy shepherds, and the luminous light of the angel. The Light of the World has been born.

Bible Reference: Gospel of Luke 2:8-20

The Annunciation, Leonardo da Vinci, detail

The Annunciation, Leonardo da Vinci, detail

Look at the glorious symmetry of this painting (see below). It echoes the Divine Symmetry of the universe.

The Angel Gabriel in this painting of the Annunciation is so beautiful, so commanding even though assuming a respectful position, that the figure of Mary is almost secondary.

Somehow da Vinci is able to convince the viewer that this is the way it should be, and is, since Gabriel is a messenger from God and therefore in a sense represents God. Respectful and bowing, yes, but also dominating.

Bible Reference: Gospel of Luke 1:26-38

The Angel of Dresden

The Angel of Dresden

This statue may or may not have been originally intended as an angel on the roof of a church in the German city of Dresden, but it certainly sent a message after the horrific bombing of Dresden in February, 1945. The sad face, the outstretched hands seem to be asking ‘Why?’ – an unanswerable question in the aftermath of war.

The statue was probably relatively unnoticed before the war, just another statue on another church in Europe. But since the bombing and the publication of the inspired photograph above, this angel has become an icon of the waste and futility of war.

We create, then we destroy.

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Heads of Angels, 1786

Sir Joshua Reynolds, Heads of Angels, 1786

The inspiration for these cherubic heads was a little girl, Frances Isabella, daughter of Lord William Gordon. The painting is simple in subject, and complex in technique.

Reynolds was fond of painting children, but perhaps not so fond of the children themselves. His small models often complained of feeling tired, but their complaints went unheard – in both senses of the word, for Sir Joshua was not only absorbed in his work, but also very deaf.

He had no children of his own, a good thing perhaps.

Annunciation, William Waterhouse, 1914

The Annunciation, by William Waterhouse, 1914

The composition in Waterhouse’s ‘Annunciation’ is spatially balanced, something you hardly notice because of the brilliant coloring. Mary is in blue, her traditional color – but what a magnificent blue, quite unlike the insipid blue of Victorian-era statues of Mary.

Everything about the picture is feminine – the flowers, the graceful gestures of both figures, the mauves, pinks and blues.

The angel offers white flowers – perpetual virginity – to the young woman. She seems at a loss, perhaps guessing the cost of accepting those flowers.

Poor girl, what a choice. It says something about her character that the Gospels contain no mention of any hesitation at that crucial moment. ‘Let it be done’ she says, and the world changes forever.

Bible Reference: Luke 1:26-38

The Archangel Leaving the Family of Tobias

Rembrandt van Rijn

The Archangel Leaving the Family of Tobias, Rembrandt van Rijn

Rembrandt never tried to make his subjects beautiful, but they often have a luminous quality, as if an inner light shines out of the uninspiring exterior. His figures are unheroic even if, as in this case, one of them is the Archangel Raphael.

And what wonderful irreverence: one can see the soles of the angel’s feet (suitably clean) and almost up his robe – the Archangel, mission accomplished, is eager to return to God. And is there any other religious painting that includes such a scruffy dog?

On the other hand, this is the only dog mentioned in the Bible who seems to have been a pet, for it follows Tobias faithfully on his long journey.

See more at Dogs in the Bible.

Bible Reference: Book of Tobit 12:20. The Book of Tobit tells the adventures and misadventures of a pious Israelite and his family. Tobit does not deserve the intense suffering he experiences. Nor does his young relative Sarah. The Book of Tobit offers an explanation for unjust suffering.

‘Angels Singing and Playing’,

Hubert and Jan Van Eyck

‘Angels Singing and Playing’, Hubert and Jan Van Eyck

These two pictures, jointly painted by the brothers Hubert and Jan Van Eyck, are panels of the great altarpiece from the cathedral of St Bavon at Ghent. Hubert, the elder by about twenty years, is supposed to be responsible for the planning and arrangement of the whole work and the painting of most of it, while Jan completed the work after his brother died.

The main difference between the two men seems to have been that the older brother was a religious ascetic and rather more restrained. The panel showing the singing angels in their sumptuous robes is said to be by Jan, and the other, that concentrates rather more on the musical instrument, by Hubert.

- Jan’s angels are a little more ordinary in countenance, and they seem to be straining with concentration.

- Hubert’s orchestra is more aristocratic, and seemingly more confident.

Notice that the organ has no keyboard as we know it; each key protrudes separately from the instrument.

The Golden Stairs, by Edward Burne-Jones

The Golden Stairs, by Edward Burne-Jones

Angels or not? There has been a lot of debate about what exactly this painting represents.

- The creatures, whatever they are, are beautiful in an unearthly way

- they carry musical instruments similar to those in paintings of the Heavenly Choirs of angel

- the Golden Stairs on which they descend seem to lead from Heaven to Earth

- and the dove visible through the skylight may represent the Holy Spirit.

But is this enough to identify them as angels, particularly when the artist, Burne-Jones, seems to leave the subject matter deliberately ambiguous? Angels should not have any features that identify them as male or female, yet the figures in this painting are clearly female. What do you think?

Angel standing at the foot of the enthroned

Madonna and Child, Giotto, Florence

Madonna with angels, by Fra Angelico,

Fiesole Church, San Domenico

The Annunciation, Fra Angelico

Madonna with angels, Fra Angelico, Fiesole Church, San Domenico, and The Annunciation

Fra (Brother) Angelico had two nicknames: the Angelic, and the Blessed; the names give us some indication of his character. His work is marked by its directness and depth of religious feeling. The attitudes of the figures are arranged with a simple formality.

The figures themselves and their costumes are sumptuous – especially in the first of the two paintings here. This is Mary as Queen of Heaven, a long way from the simple peasant girl in Galilee who answered God’s call. The angels themselves are heavenly creatures with gold leaf halos and delicate, colorful wings.

Notice the foreshortening and use of perspective in ‘The Annunciation’ – an extraordinary achievement for its day. The simplicity of the background lends a certain stillness and gravitas to the event being shown.

The Adoration of the Shepherds,

Hugo van der Goes

The Adoration of the Shepherds, Hugo van der Goes

This was painted during the middle years of the 15th century, when the rules of perspective were imperfectly understood; the panel seems to be painted in three parts and united by the addition of details such as the worshipping angels in the foreground, and the flying angels near the top. Notice the vivid way in which the faces of the shepherds are painted.

The picture is over five hundred years old, and yet the paint is so cunningly applied that every face and fold of cloth seems forcible and immediate.

Notice the tiny, unnecessary details: a summer clog; a shepherd carrying what looks like bagpipes and hurrying to catch up with the others; two beautifully dressed people leaning on a gate leading out of the inn yard (they probably paid for the painting to be done); lovely flowers put there for the sheer joy of painting them.

But notice too that most of the angels, if not all, are dressed in ecclesiastical robes of one sort or another. What message are we supposed to get from this detail?

Incidentally, Hugo van der Goes could have done some fine name-dropping. The picture above was done for a Florentine merchant who was the agent of the Medici family; his name was Tommaso Portinary, and his ancestor had been father to Dante’s Beatrice. If only we all had such connections!

Bible Reference: Gospel of Luke 2:8-20

The Fall of the Rebel Angels,

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

The Fall of the Rebel Angels, Pieter Bruegel the Elder

These are angels of an entirely different kind – fighting angels, warriors of the sky. They are led by Michael, the Angel of God.

In this painting Michael leads the Good Angels against Lucifer, the Fallen Angel who refuses to submit to God’s authority. There was a tremendous battle between Good and Evil, and Michael and his angels triumphed.

Bruegel captures the chaos and confusion of battle, and some of the macabre manifestations of Evil.

Angel Musicians, Hans Memling, 1480’s

Angel Musicians, Hans Memling, 1480’s

Poor Memling had the rather dubious honor of being the largest tax-payer in Bruges in 1480. We surmise from this that he was very successful. He painted calm, beautiful pictures, full of the restrained devotion of the later Middle Ages.

In this one, a detail from a larger painting of Christ surrounded by angels, a group of angel-musicians create the sound of heavenly choirs.

Unfortunately they don’t look very happy about it, and they have decidely weird wings, closer to a butterfly’s than a bird’s.

Notice the medieval musical instruments, quite different from a modern orchestra.

The Archangel Gabriel, Cervara Altarpiece,

Gerard David

The Archangel Gabriel from the Cervara Altarpiece, by Gerard David.

Gerard David was the last great master of Bruges, the headquarters of Dutch art at the time. This painting has all the hallmarks of his work, especially

- the technique of placing the divine and ethereal in a homely setting,

- and giving the scene, overall, an otherworldly feeling.

The subject matter encourages the viewer to overlook the superb technique behind it all. The angel is aloof but urgent. Is that hand held up in a blessing, or to catch and hold the Virgin’s attention?

Look at that superb cloak of gleaming silk. The drapery falls in rather severe folds – realistic but at the same time not quite real.

Bible Reference: Luke 1:26-38

Distraught angels at the burial of Jesus, Giotto

Distraught angels at the burial of Jesus, Giotto. Many other paintings show angels present at the death or burial of Jesus, but none that I know of show them in such anguish, such abandoned grief. See the full image below.

Giotto, the Deposition of Jesus

The Archangel Michael with spear and orb,

14th century, Byzantine

The Archangel Michael with spear and orb, 14th century, Byzantine

The Byzantine attitude to icons of Jesus, Mary and the saints was immensely sophisticated. The artist could not simply paint what he wanted. He had to take into consideration a whole range of influences including metaphysics, concern with the physical properties of light and colour, theology and symbolism.

No wonder artists were highly esteemed.

Save

Search Box

![]()

Paintings of Angels in the Bible, modern and medieval,

by some of the world’s greatest painters

Angel links

On this page

Leon Comerre L’annonce aux bergers

Da Vinci, Annunciation, detail of the Angel

Henry Ossawa Tanner Annunciation

Joshua Reynolds, Heads of Angels

William Waterhouse Annunciation

The Archangel Leaving the Family of Tobias, Rembrandt van Rijn

Angels Singing and Playing, Hubert and Jan Van Eyck

Madonna with angels Fra Angelico

Shepherds’ Adoration Hugo van der Goes

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher