Who was Esther?

Queen Vashti disobeyed the drunken orders of her husband King Ahasuerus, so he divorced her. Lonely, he sought a new queen – the most beautiful woman in the land. A young Jewish orphan, Esther, was chosen – but she was careful to keep her Jewish identity secret.

Queen Vashti disobeyed the drunken orders of her husband King Ahasuerus, so he divorced her. Lonely, he sought a new queen – the most beautiful woman in the land. A young Jewish orphan, Esther, was chosen – but she was careful to keep her Jewish identity secret.- Mordecai, Esther’s uncle, offended a high court official called Haman, who decided to kill not only Mordecai but all the Jews in the Persian empire (the first recorded pogrom against the Jews). Esther turned the tables on Mordecai. She pleaded with the king and Haman was horribly punished – hanged on the very gallows he had built for Mordecai.

- The Jewish people in Persia were saved. An annual festival (Purim) commemorated the courage of Esther and the deliverance of the Jews.

- Christianity is sometimes accused of causing the anti-Semitism that has shamed the modern world. This story shows that prejudice existed long before the birth of Jesus.

Why was Queen Vashti banished?

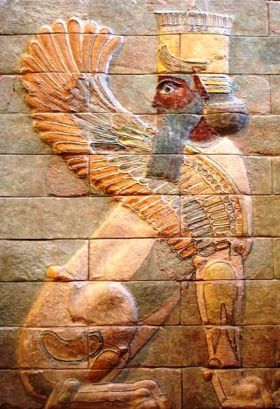

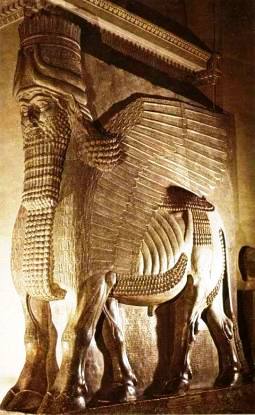

Winged sphinx from the Palace at Susa, where the banquet was held (Louvre Museum)

How do we meet Esther?

The story of Esther began at a magnificent banquet at the court of the Persian king, Ahasuerus, usually thought to be the emperor Xerxes (486-465BC).

Two banquets – why?

There were two separate banquets being held:

- one for the king, his councillors and all the important men of Susa

- the other given by Queen Vashti, for the women of the court and nobility.

You can read Herodotus’ description of one of Xerxes’ great banquets in Herodotus Book 7, section 116-123: ‘Pausanias, seeing Mardonius’ establishment with its display of gold and silver and gaily colored tapestry, ordered the bakers and the cooks to prepare a dinner such as they were accustomed to do for Mardonius…’

The King’s banquet. What went wrong?

Having drunk far too much wine, King Ahasuerus sent for his Queen. He ordered her to appear before the men at his banquet. She was noted for her beauty, and he wished to show her off to the men of the city.

What was the queen’s reaction? The Queen of the Persian Empire was chosen from among the seven most ancient and noble families of the empire, and Vashti was of ancient and noble lineage.

Drunk with wine he sent for his beautiful queen, Vashti, to appear before the men. She refused to come. Humiliated, the king banished her. But now he was lonely, so a search was made: the loveliest girl would become his new queen.

She would not have relished the prospect of being paraded in front of a room full of drunken men – it was not a suitable thing for a queen to do. Men and women often dined together in ancient Persia, but as the dinner progressed and more wine was drunk, the wives left the dining area, and were replaced by concubines.

She refused to come.

On the seventh day, when the King was merry with wine, he commanded the seven eunuchs who attended him to bring Queen Vashti before the King, wearing the royal crown, in order to show the peoples and the officials her beauty; for she was fair to behold. But Queen Vashti refused to come. At this the King was enraged, and his anger burned within him. Read Esther 1:1-22.

Why did Vashti refuse to appear?

Vashti may have thought she was being treated as a concubine, rather than as a wife and queen. She behaved with haughty dignity when she refused the king’s command, but unfortunately her answer was given in front of the officers of the empire, and she paid the price for humiliating the king.

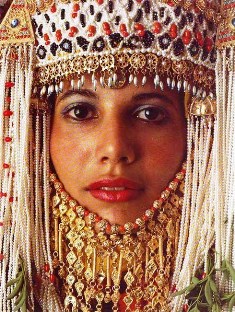

Esther: Middle Eastern woman with wedding headdress

What was the King’s reaction to his wife’s refusal?

Ahasuerus, still half-drunk, acted hastily. On the advice of cowed and inept councillors, he made the situation worse by issuing a public decree that Vashti was to be banished. This drew even more attention to the fact that Vashti had flouted his command, and made him look a fool to all his subjects.

At this stage in the story, it becomes obvious that this is not a traditional story about a good king. Ahasuerus was a despot who was also a fool.

So a theme begins to emerge: unlimited power, exercised without wisdom, is a dangerous thing.

The lonely King

After a while Ahasuerus found that without Vashti, ‘the beloved one’, he was lonely. He could not call her back because his word, once spoken, was law. So his courtiers suggested a solution: to find another queen, a young and beautiful woman who would take Vashti’s place.

Then the King’s servants who attended him said ‘Let beautiful young virgins be sought out for the King. Let the King appoint commissioners in all the province of his kingdom to gather all the beautiful young virgins to the harem in the citadel of Susa under custody of Hegai, the King’s eunuch, who is in charge of the women. Let their cosmetic treatments be given them. Let the girl who pleases the King be Queen instead of Vashti.’ This pleased the King, and he did so. Read Esther 2:1-23.

Map of the Persian Empire at its greatest extent

The search for a beautiful virgin

A nation-wide search for a new queen began – the first recorded beauty contest.

A young Jewess was among the candidates. Her beauty was so extraordinary that she ‘pleased’ even the chief eunuch Hegai, who had been castrated while still a boy – there is a note of irony here.

One wonders too at the back story to all this: did Hegai play some part in deposing Vashti?

Gold torque with lion heads, circa 350BC, excavated at the palace at Susa

Esther prepares – and it works…

Esther with all the other young virgins was taken into the harem, and twelve months of careful preparation began. She was shrewd enough to seek the advice of Hegai, who knew the king’s tastes.

Eventually she went to the king, and pleased him so much that he set the royal crown on her head. She became queen in Vashti’s place – with all the wealth and power of an Eastern queen now suddenly at her disposal.

Why did Esther’s story mean so much to Jews?

- Esther was a symbol of Jews who lived successfully in an alien culture.

- As a woman, she was not in a position of power, just as Diaspora Jews were not members of the power elite.

- As an orphan, she was separated from her parents, as Diaspora Jews are separated from their mother-country.

- With both these handicaps, she had to use every skill and advantage she had, as Diaspora Jews did. They, like Esther, had to adapt themselves to the situation.

Esther & Mordecai

Gold and lapis lazuli headdress from the tomb of Queen Puabi, from the Sumerian city of Ur.

From the start, Esther had been helped by her cousin Mordecai, but nobody knew that they were related, or that Esther was a Jewess. Esther did not keep the dietary laws of Judaism, or retain the practices of an orthodox Jewess.

God is never mentioned directly in the story. So the story is not a ‘religious’ story as such, but a secular one, about pragmatism in the face of adversity.

Not long after her installation as queen, Mordecai found out about a plot to assassinate the king. He told Esther, who in turn warned the king. The plotters were hanged, and Mordecai’s warning was recorded in the court annals.

Esther Saves Mordecai

The story that follows in chapters 3-8 gives details of a personal conflict that escalates into a nation-wide pogrom against the Jewish people.

Mordecai refused to bow to the highest court official, Haman the Agagite. In a court with strict protocol, Mordecai’s refusal to bow was a grave insult, and a feud started between the two men.

When Haman saw that Mordecai did not bow down or do obeisance to him, Haman was infuriated. But he thought it beneath him to lay hands on Mordecai alone. So, having been told who Mordecai’s people were, Haman plotted to destroy all the Jews. Read Esther 3:1-15.

There is no reason given for Mordecai’s refusal to bow. It was not against normal Jewish practice to bow to a ruler or his representative (see Joseph and his brothers in Egypt, Genesis 43:26).

But Mordecai’s ancestor Saul had been an enemy of Haman’s ancestor Agag, king of the Amalekites (see 1 Samuel 15), and this may have been Mordecai’s reason.

In any case, he did not follow the accepted practice, and thereby placed himself and others in danger.

Two Persian court officials

Haman’s anger shifted. It had been focused on Mordecai, but finding that Mordecai was a Jew, his fury expanded to include the whole Jewish people.

In a scene that formed a blueprint for anti-Semitic propaganda, Haman fed the mind of the king with ideas about a people who were different, who obeyed different laws, and who were a danger to the kingdom.

He sought ‘the final solution’.

The Jews, said Haman, must be eliminated for the good of the kingdom. The king agreed, not knowing that Esther, his beloved queen, and Mordecai, the man to whom he owed his life, were both Jews. A day was set aside for the slaughter, and a decree issued to every corner of the empire.

Sacral kingship: the king is a god…

The absolute power of the king seems strange to us, accustomed as we are to the democratic rule of law.

But in many parts of the ancient world a king was thought of as a living god.

- He was a sacred person who embodied, in his person, the state or kingdom that he governed.

- His physical body was clearly not immortal, but he was thought of as someone who was more than human, with a special and unique connection with the immortal gods.

- Because of this, he could do what he wanted even when, as in this case, it was clearly unjust.

Rembrandt’s painting of Esther. See link to Famous Paintings of Esther at top right of this page

This concept of sacral kingship was rejected by Israel. From earliest times it saw God as its ruler. Its laws came from God, not from the state.

When it did have kings like David or Solomon, it emphasized their humanity. In the Israelite mind, kingship was very close to tyranny, and had to be constantly hedged around with precautions to stop it becoming despotic.

In the crisis that was about to engulf him, Mordecai turned to Esther. She alone could save the Jewish people from the stupidity and cruelty of her husband the king.

But there was a problem – Esther had not been summoned into the royal presence for thirty days, an ominous sign that she might be losing favour in his eyes. To approach her husband without being first commanded was breaking the law, and she would be punished by immediate death.

She was aware of this, but her reaction was fatalistic: ‘If I die, I die’.

Esther risks death

Then Esther said in reply to Mordecai ‘Go, gather all the Jews to be found in Susa, and hold a fast on my behalf, and neither eat nor drink for three days, night or day. I and my maids will also fast as you do. After that I will go to the King, though it is against the law; and if I perish, I perish’. Mordecai then went away and did everything as Esther had ordered him.

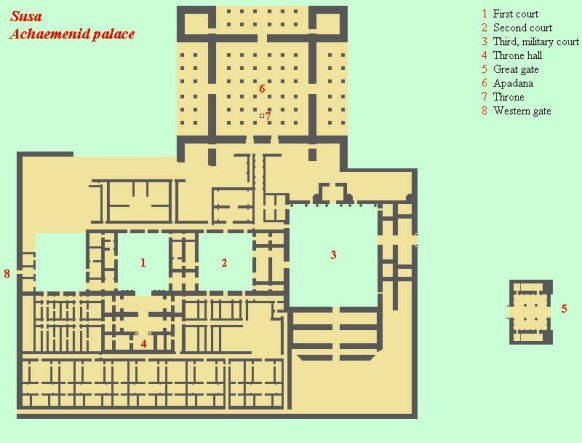

Floor plan of the palace at Susa

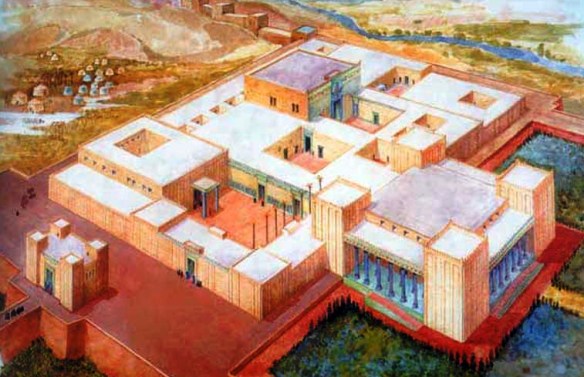

Reconstruction of the ancient palace at Susa.

Note the position of the throne room, at the center of the building.

Capitals from the roof in the throne room at Susa; the Louvre, Paris

At enormous personal risk, Esther broke the law and went into the throne room of Ahasuerus. (This incident has been popular with artists. Go to Bible Art: Esther for about thirty-five paintings of Esther by some of the world’s great painters – see especially the so-called ‘Fainting Paintings’.)

‘As soon as the King saw Queen Esther standing in the court, she won his favour and he held out to her the golden sceptre that was in his hand. ‘

Ahasuerus seemed charmed by her unexpected appearance. Taking advantage of his good humour, she asked him if he and Haman would come to a banquet she meant to hold. He agreed.

Haman suspected nothing, believing he was being honoured by her invitation. He and the king attended the banquet, and Ahasuerus promised Esther that she could have anything she wanted – even half his kingdom. This was an extravagant offer, highlighting the foolish recklessness of the king.

Shelves with hundreds of ancient scrolls

Esther asked that the king and Haman attend a second banquet the next day. The king agreed.

In high spirits, Haman returned to his home and ordered the erection of a gallows, to hang the enemy he hated, Mordecai. But during the night, Ahasuerus could not sleep. He told his servants to read from the records of his reign.

As they read, he was reminded of the good deed of Mordecai. He realized he had never rewarded him, and decided to remedy this. As it happened, Haman was there, and the king asked him how he could reward someone who had been a remarkable servant.

So Haman came in, and the King said to him ‘What shall be done for the man whom the King wishes to honour?’

Haman is caught in his own trap

Haman, thinking the King was referring to himself, recommended extravagant rewards. The King agreed, but then astonished Haman by telling him that it was Mordecai he wanted to reward. Haman was mortified by his mistake, and hated Mordecai even more. Zeresh, the wife of Haman, warned him, but he was now so eaten up by hatred that he could not turn from the path he was following.

-

The winged bull sphinx, symbol of the absolute power of the king

Meanwhile, Esther’s banquet had been prepared. Ahasuerus was so pleased by it that he again promised Esther anything she wanted.

There’s a similar story in Herodotus Book 9.109-113, where the Persian king Xerxes makes a promise to his wife Amestris.

‘As time went on, however, the truth came to light, and in such manner as I will show. Xerxes’ wife, Amestris, wove and gave to him a great gaily-colored mantle, marvellous to see.

Xerxes was pleased with it, and went to Artaynte wearing it. [2] Being pleased with her too, he asked her what she wanted in return for her favors, for he would deny nothing at her asking.

Thereupon—for she and all her house were doomed to evil—she said to Xerxes, “Will you give me whatever I ask of you?” He promised this, supposing that she would ask anything but that; when he had sworn, she asked boldly for his mantle.

[3] Xerxes tried to refuse her, for no reason except that he feared that Amestris might have clear proof of his doing what she already guessed. He accordingly offered her cities instead and gold in abundance and an army for none but herself to command. Armies are the most suitable of gifts in Persia.

But as he could not move her, he gave her the mantle; and she, rejoicing greatly in the gift, went flaunting her finery.’ (Herodotus Book 9.109-113).

This story, as you would guess, also ends in torture and bloodshed.

In the Bible story, Esther responds to Ahasuerus’ promise with a much more significant request. She asks that her life be spared and her people saved. From whom? asked the King. From Haman, replied Esther.

When the King returned from the palace garden to the banquet hall, Haman had thrown himself on the couch where Esther was reclining; and the King said ‘Will he even assault the Queen in my presence, in my own house?’

The Feast of Esther, by Edward Armitage

Haman was trapped. He was taken out by the king’s servants and hanged from the gallows he had built for Mordecai – see Bible Heroes: Mordecai. He did not repent of his hatred for the Jewish population. He begged for his life, but gave no indication that he had experienced any change of heart.

Esther had saved Mordecai from Haman, but the Jewish population was still in danger.

Esther saves the Jewish people in Persia

Esther pleaded with the King.

The King held out the golden sceptre to Esther, and Esther rose and stood before the King. She said ‘If it pleases the King, and if I have won his favour, and if the thing seems right before the King, and I have his approval, let an order be written to revoke the letters devised by Haman son of Hammedatha the Agagite, which he wrote giving orders to destroy the Jews who are in all the provinces of the King. For how can I bear to see the calamity that is coming on my people? Or how can I bear to see the destruction of my kindred?’

Queen Esther, by Andrea del Castagno

So letters were again sent to every corner of the empire, halting the order of execution on the Jewish population.

Esther had made not a single false move:

- in the harem, as a young girl in training to be a wife and queen

- in danger, coolly keeping her head instead of panicking.

Her speech in 8:5-6 showed her skill in diplomacy.

The Jews were not only saved from death: they could also attack those people who had been their enemies, and could claim their property. On the very day that they were to have been annihilated, they turned the tables by destroying all those who had sought to kill them. Thousands were killed, including the ten sons of Haman.

From that day on, the Jewish people kept the day as a special festival called Purim. It was a day when gifts were exchanged among members of each family, and presents given to the poor.

It commemorated the day the Jewish people were saved by Esther.

Extra Snippets about Esther

Ahasaurus, Haman and Esther at the banquet, Rembrandt

‘The book of Esther reflects the situation of the diaspora, and one of the reasons it was produced was certainly to address the needs of the Jewish community living outside Palestine.

The story is set after the Exile and is part of the postexilic period of Israelite history, when many Jews were living away from the homeland of Judah. As is often observed, there is no concern for items and ideas that feature prominently in other Israelite literature: land promised to the ancestors, the Jerusalem cult, Torah observation, or an autonomous Israelite state under a divinely appointed monarch.

The book of Esther does not suggest that the goal of proper Jewish living is to return to Judah; instead, it promotes the idea that Jews can live personally fulfilling, and even socially successful, lives in exile from Palestine.

It asks who are we, if we not only do not live in Judah, but also do not even want to?’

‘Esther’, Linda M Day, p.12

‘Although it seems that the young women had no choice about the length and nature of their preparation, when their turn arrived and they were moved from the harem to the king’s private quarters, they had some say about how they presented themselves.

Whatever the girl asked for may have included items of clothing or jewelry or aphrodisiac foods (some of the descriptions of preparations for love-making in Song of Songs provide possible insight here). The writer does not supply the details but leaves that to the readers’ imagination.

The provision of ‘anything’ contrasts with Esther’s modest request in verse 2:15, and is a feature of Esther’s queenship – she is often given the chance to ask for anything.’

‘Esther’, Debra Reid, p.82.

A tomb in Iran, said to belong to Esther and her uncle Mordecai

What are the main themes in Esther’s story?

- Let God be your ruler: Esther’s story was a political satire, showing the danger of giving absolute power to someone who might be a fool. Ahasuerus governed by whim rather than by wisdom, becoming the tool of anyone shrewd enough to exploit him. The lesson is clear: do not give too much power to any one person; in the long run God alone should rule us.

Right Living: the Book of Esther was written for Diaspora Jews (Jews who lived outside Israel), to show them how to live in exile. If they encountered bigotry and prejudice, they must act with courage, wisdom and integrity.

Right Living: the Book of Esther was written for Diaspora Jews (Jews who lived outside Israel), to show them how to live in exile. If they encountered bigotry and prejudice, they must act with courage, wisdom and integrity.- The origin of Purim: the story explained the origin of a major Jewish feast day.

Names in Esther’s story

- ‘Esther’ means ‘hidden’ – her Jewish identity was hidden from the King. Esther’s Jewish name Hadassah, means ‘myrtle’, a tree whose leaves release their fragrance when crushed.

- Ahasuerus means ‘ruler of heroes’; he is thought to be based on the Persian emperor Xerxes, whom Leonidas fought with the famous ‘300’.

- Vashti means ‘sweetheart’ or ‘beloved’

The names Esther and Mordecai may be related to stories about the Persian deities Ishtar and Marduk. Ishtar (stareh, a star) was the Babylonian goddess of love. Marduk was the principal male god of Babylon. Haman and Vashti may correspond to the Elamite gods Humman and Mashti.

These similarities suggest that the Book of Esther was based on an older Babylonian story that the Jewish people heard during the Babylonian exile. (See The Jewish People in Exile)

Search Box

![]()

Finding a Husband

Compare with Ahaseurus’ way of choosing a wife

Movies often tell stories about the dangers for women like Esther, who lived in a treacherous royal court.

with the famous

‘Fainting Paintings’

Esther married a fool who impulsively divorced his first wife when his advisers told him to do so. Then he chose a second wife for her beauty – all very fine, but the queen of a vast empire needed more than beauty to survive in a corrupt and dangerous court.

Heroines

of the Bible

© Copyright 2006

Elizabeth Fletcher